Transit-oriented development in the Chicago region is falling behind cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco, according to a report released in May by the Center for Neighborhood Technology, a local "think and do tank." In "Transit-Oriented Development in the Chicago Region" [PDF], CNT warns that Chicago's failure to focus housing and jobs near transit is creating additional financial burdens for households who have no choice but to shoulder the costs of car ownership.

Transit-oriented growth has myriad benefits. It cuts pollution. It reduces traffic. It promotes public health by enabling people to walk more and lowers household costs by letting them drive less. But despite the region's extensive transit system, Chicagoland is not capturing these benefits. In recent years, most housing development in the region has essentially continued to follow a sprawling pattern, beyond the reaches of existing transit.

In the report, CNT compares Chicago to the four other regions in the United States that have transit systems with more than 325 stations -- Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco -- looking at how much development is occurring within a half-mile of transit stations (the "transit shed"), and how much is being built farther away.

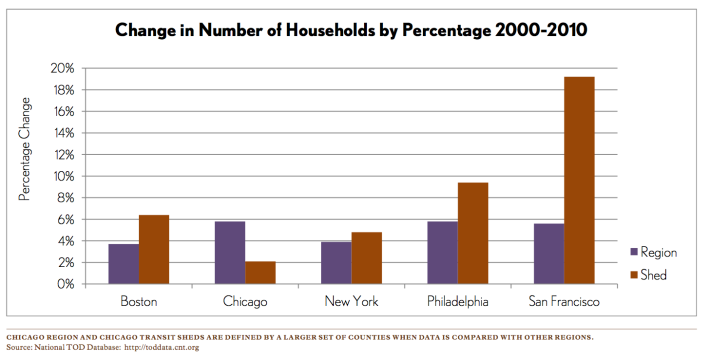

Only in Chicagoland did CNT find that housing is growing more rapidly outside the transit shed than inside. From 2000 to 2010, most growth in the region happened in places unreachable by Chicago Transit Authority and Metra trains:

Urban sprawl has continued to be the dominant development pattern in the Chicago Region, with households increasingly dispersed around the Region and a growing proportion of the Region’s households living more than a half-mile from a transit station.

This means that new development has tended to generate more traffic, pollution, and household expenses, instead of fostering walkability and lower costs of living.

The report also notes that Chicago's share of families living near transit is declining faster than in other cities. Chicagoland had the largest decreases in average household size compared to its peer regions. Even new housing built within the transit shed tended to be small, "one- and two-bedroom condos marketed to empty nesters and professionals," according to CNT. A big factor, the authors write, is the elimination of 5,703 households on Chicago Housing Authority property.

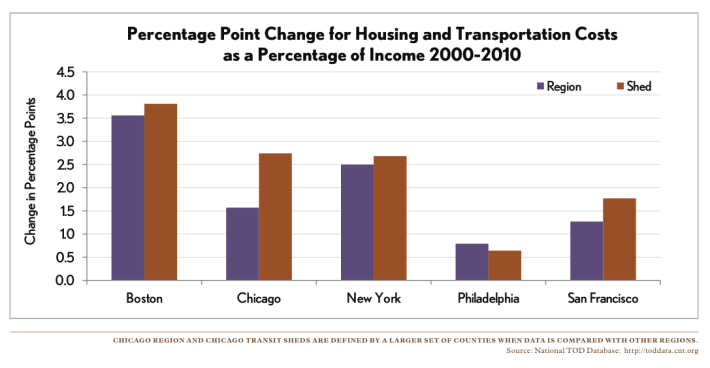

Housing and transportation are the two biggest components of household spending. Living near transit offers residents more travel choices and decreases household transportation costs. However, housing costs in the transit sheds of Boston, Chicago, and New York increased faster than outside the transit sheds. Affordable housing must be preserved or built in the transit shed, concludes CNT, so that "low- and moderate-income households can benefit from the Region’s investment in public transit, as well."

While combined housing and transportation costs remain lower in Chicago's transit shed, they are increasing faster near transit than in the region as a whole. This was true in Boston and New York as well. According to CNT, "if this trend continues it means moderate- and lower-income households (i.e. young singles, families, renters, affordable housing beneficiaries) will increasingly have difficulty living in the transit shed."

The report notes that the median household income rose more in the Chicago transit shed than in the region, which could be a sign that lower-income households are being displaced. This was also the case in every peer region except Philadelphia, but Chicago saw the greatest disparity between the increase in median household income in the transit shed and in the rest of the region.

Oddly enough, another issue in Chicagoland is that driving is increasing more in the transit shed than in the region. CNT says one possible explanation is that median incomes are higher in the transit shed, and this may lead to higher car ownership and more driving. Thankfully, though, residents in the transit shed still drive less than people outside – this was consistent across all five regions.

Finally, there's the issue of where jobs are located. The rate of job loss from 2000-2010 was significantly higher in the transit shed (-1.3 percent) than in the region as a whole (-0.5 percent). The report mentions the historical trajectory of transit and job access in Chicagoland. While downtown is the core location for jobs, satellite job centers have appeared, "developed in locations underserved by transit, which is restricting employment to those who own cars and are willing to drive to work." Job sprawl goes hand in hand with housing sprawl: As people search for cheaper housing not served by transit, they then have no choice but to shoulder the expense of car ownership and drive long distances to work.

Jobs are moving away from the central business district faster than transit is. Most of the transit shed – 80 percent – is in Cook County, the home of downtown Chicago. But the collar counties are experience greater job growth than Cook County, and it's "this disconnect," the authors note, that makes it a challenge for cities "to provide employment for people who may not be able to afford the transportation costs associated with suburban employment."

So those are some of the alarming development trends in Chicagoland. In a follow-up post, we'll look at the solutions and how Chicago can promote more equitable growth near transit.