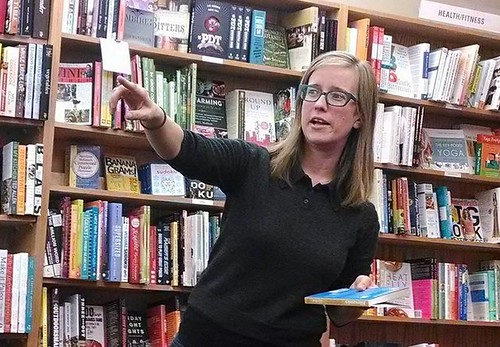

Bike Writer Elly Blue Discusses the Economics of Cycling

1:49 PM CST on November 26, 2013

On Friday I had the pleasure of moderating a discussion of cycling and economics with bike writer Elly Blue, author of the new book “Bikenomics: How Bicycling Can Save The Economy,” at City Lit bookstore in Logan Square. Blue’s work has appeared in various biking, sustainability, and feminist publications, and she’s also the author of “Everyday Cycling,” a great beginner’s guide to using a bike for transportation. She blogs at TakingTheLane.com.

“Bikenomics” looks at the current cost of transportation for individuals and families, as well the economic toll of our car-centric transportation system on municipalities, states and the federal government. The book also tells stories of people, businesses, organizations and cities that are investing in bicycling. Here are a few excerpts from Friday’s conversation, which included plenty of input from the audience members, largely people who bike commute regularly.

The value of protected bike lanes

John Greenfield: A big thing here in Chicago is protected bike lanes. The mayor has promised to install 100 miles of protected lanes -- they’ve sort of adjusted it to be 100 miles of protected and buffered bike lanes -- within his first four years in office. It’s been a little bit controversial. Some of the lanes involve road diets, narrowing or removing travel lanes in order to make space for the protected lanes. So what would you say to Chicagoans who question the value of protected bike lanes? What are the economic advantages?

[Elly asked the audience what they think about PBLs, and a few people expressed skepticism, citing issues with maintenance, sight lines, and cars parking in the lanes.]

EB: I’m a believer in good bike infrastructure and building a proper bike city, but I think you can’t just put in certain kinds of bike infrastructure on some roads and leave it at that. I mean you also have to take the cars off the road, make them smaller, make them slower and make sure that you have to be going slow enough to be paying attention when you’re driving them and do all sorts of other things as well.

I think the real benefit of protected bike lanes is, on the one hand you have a much better riding experience. You still need to pay attention. You can’t just pretend you’re off in the country by yourself, but they do make it possible for people to bike on a road that they would not have considered biking on otherwise. It brings people and it sort of is, as I say in the book, like a vaccine for a neighborhood, where you can take the first steps needed for transforming a place, making the businesses along the street do a little bit better, making the street something that other people in the neighborhood will use as well.

One of the biggest arguments in favor of them is safety, and it’s not just bike safety. They’ve done studies in Philadelphia and New York City and a few other places. When a protected bike lane comes in, it has a traffic calming effect. This results in slower travel speeds and also fewer crashes involving everybody by all modes of transportation, so fewer bike crashes, but also car crashes and fewer pedestrian injuries.

I think the number of all injuries to all users in Philadelphia went down 65 percent [the number is actually a still-impressive 44 percent] after they put in their protected bike lanes. And that’s huge. You’re always going to have someone saying, “This was a safe city until those bicyclists came in and started rampaging all over the streets,” but those people are not speaking from a place of statistics.

And the safety advantage is a huge economic one. It’s not just in terms of somebody not going to the hospital today when they were going to go to work or going to go shop at a store, and crews not having to come out, but also the general feel of the neighborhood improves. So you’ll have more people shopping at stores and spending money.

The economic benefits of bike-share

JG: Anything you want to say about the economic benefits of bike-share?

EB: Yeah, it takes away several of the barriers to riding a bike. Some of that is economic. For the cost of ten or twelve taxi rides per year, you can basically get anywhere in the city. You don’t have to own a bike and you don’t have to store a bike. I think one of the biggest barriers to riding a bike, among people I’ve observed, is they have a bike sitting in their living room for years with a flat tire. Bike-share really takes that away. Or they’re like, “Oh, I don’t know, I have this bike light but I think it needs batteries.”

JG: One thing we’re going to see a lot in Chicago this winter is, road salt is a huge thing here. A mayor [Michael Bilandic] lost an election because he didn’t clear the snow in time. So nowadays mayors are paranoid. They salt the road if there’s even a prediction of snow. So I think there are going to be a lot of Chicagoans using bike-share instead of using their own bikes on the road, to spare them from winter grime.

EB: Which is going to be really interesting for the people managing the bike-share.

JG: Yeah, they’re going to have a lot of maintenance work to do. I hope they’ve got a lot of chain lube.

The current bicycle infrastructure building boom

Audience member: What’s driving all this cycling infrastructure? No pun intended…

EB: I wish I knew. This is basically a book about cars and kind of the failure of the world that we have built for cars and the investments that we have made. Those investments are failing. There’s a guy named Charles Marohn that has a blog called Strong Towns that I highly recommend. He’s a small-town Midwestern Republican and a big bike advocate, and his whole reasoning is if you do the math behind the big infrastructure projects of the past century, they’ve all had a limited lifespan. When they failed, cities have had to figure out how to repay them and take out massive loans. When they reached the end of their life again, those loans still aren’t paid off, so you have to invest even more deeply and dig even more deeply, and as the economy has burst we’ve had less access to that kind of money.

And also by doing all of these things, like building outlying suburbs, which involve new roads and new utilities, we haven’t just bankrupted ourselves civically, we had the whole housing bubble and we bankrupted our families as well. And we basically lost our ability to have access to exercise, access to good education, access to groceries, access to community. We built these places that are really not nice to live in. There’s kind of a growing class divide. The suburbs are becoming much poorer and the inner cities are becoming much wealthier. There’s just this sort of desperation.

People want and need a major change, and bicycling is one of the things that really can give you that in a way that you can afford, that the city can afford, and that actually brings wealth back into the economy. That’s sort of my highfalutin answer to your question. People are really hungry to do things like change light bulbs, but changing light bulbs is not satisfying and doesn’t change your life. But riding a bike gives you all of that and it’s fun.

In addition to editing Streetsblog Chicago, John writes about transportation and other topics for additional local publications. A Chicagoan since 1989, he enjoys exploring the city on foot, bike, bus, and 'L' train.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Chicago

It’s electric! New Divvy stations will be able to charge docked e-bikes, scooters when they’re connected to the power grid

The new stations are supposed to be easier to use and more environmentally friendly than old-school stations.

Today’s Headlines for Tuesday, April 23

Communities United: Reports of Bikes N’ Roses’ death have been greatly exaggerated

According to the nonprofit shop's parent organization, BNR has paused its retail component, but is still doing after-school programming and looking for new staff.