A research team from the Chicago-based mobility justice group Equiticity interviewed low- and middle-income Black and Latino residents of Chicago’s South and Southwest sides, asking them to compare transportation access in their community to that of other parts of town. One participant noted that the quality of pedestrian, bike, and transit access and infrastructure on the South Side often lags far behind that of the North Side, calling the situation "annoying, confusing, and... irritating."

The study, tiled "Lived expertise for epistemic justice and understanding inequitable accessibility," is part of a larger Equiticity research project to analyze and address structural racism in transportation. Streetsblog reported on a previous paper in the project by University of California Davis environmental science and policy professor Jesus Barajas, that examined the disproportionate rate of ticketing for bicycle infractions in majority-Black neighborhoods, titled "Biking Where Black."

In the new study, Barajas, along with Kate Lowe, associate professor of Urban Planning and Policy at University of Illinois Chicago, and research coordinator Chelsie Coren of Northwestern University, make the case that equitable transportation planning must include not only technical experts, transportation agencies and politicians, but also the community members who are supposed to benefit from the initiatives.

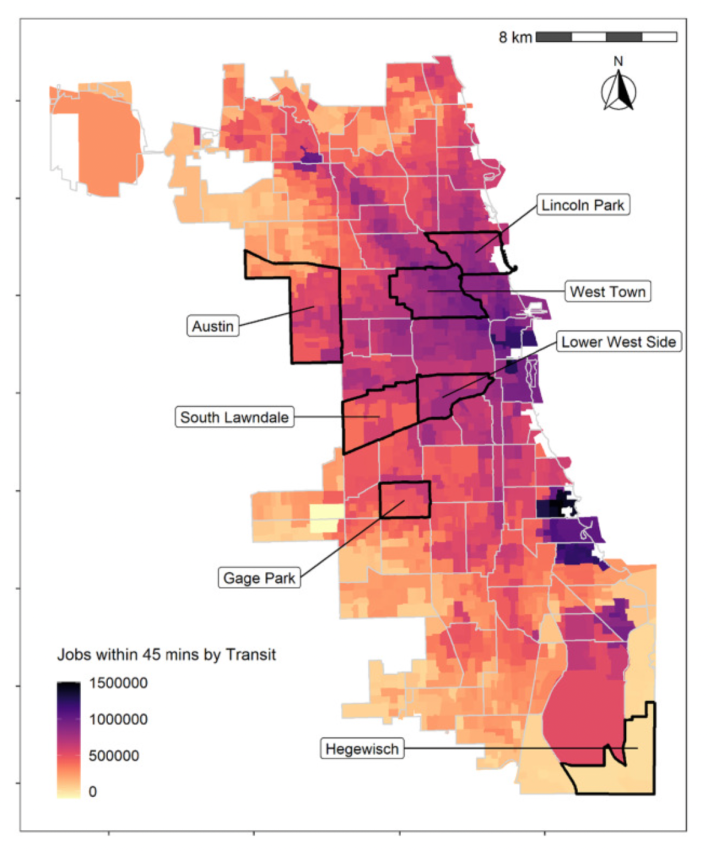

The authors argue that people who live in underserved neighborhoods bring a crucial “lived expertise” to the planning process. That's because they have a complex understanding of compound inequities they live with and are forced to adapt to every day. Their neighborhoods may have sub-par access to transit access and grocery stores; dangerous conditions for walking; high poverty rates and poor health outcomes; plus other issues. These day-to-day realities dictate how people use the transportation system.

With help from other Equiticity staffers and the Metropolitan Planning Council, the research team held focus groups to gather input from 150 participants on how they get to the various places they need to go, and the obstacles they encounter. The researchers found mobility barriers were “numerous and varied, from missing or icy sidewalks, to slow or stressful transit service.” However, a few common themes emerged.

Notably, safety was a frequently mentioned issue. The paper states, "concerns about crime and violence came up in every focus group session, even though no questions in the focus group guide directly asked about it." Participants reported feeling unsafe walking through their neighborhoods to get to their destinations, or to bus stops or train stations. Out of concern for safety, several respondents said they feel they need to use private cars or ride-hail, which many reported as giving them a feeling of autonomy and control. Some respondents said they skipped certain errands and activities entirely. One told the facilitator, "Now you know the reasons we don’t go shopping."

Another safety concern was being targeted by police while making trips by bicycle or car. One participant discussed police targeting bicyclists of color, particularly in African-American communities: "I know people have had issues with like being stopped by the police to check and see if that’s their bike. Is it registered? So it’s like… note to everybody who has a bicycle, make sure you register your bike. So you get stopped and it doesn’t happen up North."

It's likely illegal for police to stop people on bikes solely to check whether their ride is registered. But Chicago Police Department spokesperson Glen Brooks basically admitted during a 2018 WTTW "Chicago Tonight" discussion of bike ticketing that the force uses zero-tolerance enforcement of minor infractions like sidewalk cycling as a pretext to conduct searches for guns and drugs: "When we have communities experiencing levels of violence, we do increase traffic enforcement."

In "Biking Where Black," Barajas found that aggressive policing of bicyclists in predominantly Black neighborhoods is exacerbated by a dearth of bike lanes, let alone protected lanes, on busy streets with fast-moving traffic and heavy truck use. That causes many bike riders to use the sidewalk, providing an excuse for frequent police stops, searches, and ticketing. Given our city’s history of racist and violent policing, Barajas and his co-authors of the lived expertise study warn against increasing police presence to reduce crime, and recommend addressing root causes of violence through equitable investment in housing, healthcare, education, employment, and other areas instead.

Another more subtle concern for safety – or at the very least comfort – was voiced by respondents who felt hyper-visible and self-conscious while riding public transportation. One participant said, "Just being African-American, especially when you have a certain look, then you’re not as, call it, clean cut how they want you to be… A lot of people kind of just gravitate their eyes toward you, and you can feel that."

Through these personal accounts, the study attempts to demonstrate just how complex inequitable access to basic life necessities is. It encompasses not only the transportation system, but destinations: How far and for how long must an individual travel to reach their workplace, school, pharmacy, or grocery store? What is their experience during the journey? One respondent, who was quoted at length, tidily summarizes the virtuous cycle of walkable neighborhoods:

We don’t really live in walkable cities where no matter where you live really kind of supports what you need. So if we had that more people could walk. You would probably feel safer cause you’d be in a type of community where you tend to know people, like even, you know, police well enough that they’re cool with you. They know you… a genuine sense of community would be created. You’d be able to walk more places and that’d be more environmentally and economically sound. And then a little further places, you bike. And then of course for longer distances you would have better public transportation.

The authors argue this vision of safe, walkable, well-connected neighborhoods across the entire city can only be designed through collaborations between transportation planners, and experts in intersecting fields like public health and human services. But it's equally important, they note, to consult those living in the relevant neighborhoods who use the transportation system every day.

Read "Lived expertise for epistemic justice and understanding inequitable accessibility" here.

If you appreciate Streetsblog Chicago's livable streets coverage, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to help us raise $50K by 1/31 to fund our next year of reporting. Thank you.