Last Wednesday's community meeting about the $262.3 million rehab of the section of the Union Pacific North line that runs through the tony Lincoln Park and Lakeview neighborhoods was supposed to be in an open house format. But the roughly 40 residents in attendance insisted on a town hall-style format, where they could publicly voice their concerns that the project will impact their quality of life and lower property values, and they refused to take no for an answer.

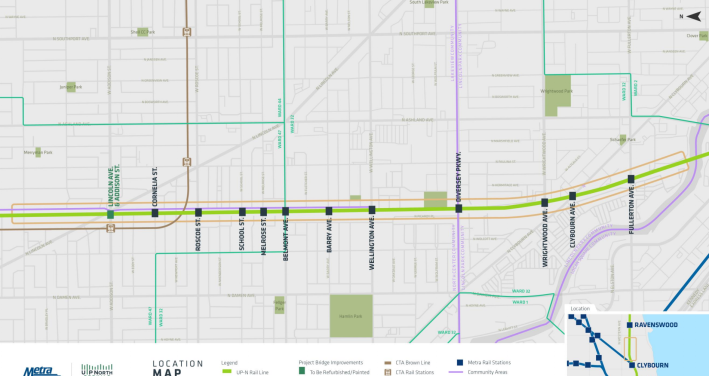

Metra and Union Pacific Railroad, which owns the rail line, are currently developing a plan to replace bridges, shore up embankments, and improve viaducts between Fullerton Avenue (2400 N.) and Addison Street (3600 N.) But the most contentious aspect of the project is that Metra and UP plan to shift the railroad tracks west, closer to local homes.

Background

The UP-N line previously had three tracks, but the westernmost one was removed in the 1980s. Metra is planning to do what it previously did between Grace Street (3800 N.) and Balmoral Avenue (5400 N.) in Edgewater and Uptown. There the railroad built a new west track, then replaced the center part of the bridge that would hold the new east track, and then removed the old east track section. With this method, there are always two tracks in service throughout the entire process.

As Streetsblog has previously reported, the current plan calls for replacing 11 railroad bridges, refurbishing the newer Addison/Lincoln bridge, improving the viaducts, adding lighting, and making the sidewalks wheelchair-accessible. The project will also lower Roscoe Avenue (3400 N.) and Cornelia Street (3500 N.), which are located south and north of the spot where the CTA Brown Line passes over the Metra tracks. In addition, the work includes refurbishing the embankment structure and add retaining walls on the west side of the embankment, plus a few sections of the east side of the embankment.

Concerns about just how far west the new west track will be located came up during the first meeting about the project last September. Neighbors became more worried when Metra gave the preliminary answer earlier this year. The center of the westernmost track will be moved 20 feet west, that is, 13 feet east of the west edge of the embankment, and the retaining walls will be a foot from the neighbors' property lines.

The new infrastructure will stay within the current Union Pacific right of way. However, the project will put trains closer to many balconies and decks, and some neighbors who have in effect used the UP-owned land as an extension of their backyards may lose that privilege. Metra also acknowledged it they may need to temporarily occupy some private property to stage equipment.

People who live directly west of the tracks recently told Block Club Chicago that when they bought their homes, they knew the railroads had the right to move the tracks further west, but indicated they didn't expect that would actually happen. Moreover, some neighbors have been gardening on railroad property next to their homes, even though they understood it wasn't their land.

For example, below is a before-and-after rendering provided by Craig Gunderson, a resident of Picardy Place. That's a row house development north of Diversey Parkway (2800 N.), just west of the tracks, which one real estate listing described as “a highly desirable private gated community.”

The confrontation

The open house took place in two different rooms, with the south room used to share project details and the north room used to share the preliminary results of environmental studies. According to the presentation boards, the study “preliminarily determined that this project would likely not have significant adverse environmental impacts.” That doesn’t guaranteed that it won’t, just that it probably won’t based on preliminary findings. The Noise and Vibrational Analysis found that the decibel increases would be within 1.7 – 2.3 decibel range, which falls well within the “barely perceptible change” range.

As the meeting went on, neighbors gathered in the northern room to demand that the project staff hold a town hall. When they made their move, neighbor Brenda Barrie led the charge. The project staff initially stood their ground, and at one point a Metra police officer tried to persuade the crowd to back off. But the officials eventually relented and agreed to set up a panel in the south room.

As the town hall got underway around 6:50 p.m., Barrie asked several questions from a prepared list, which focused on what rights the residents have to challenge the project, and who makes the decisions.

The residents expressed concerns that the changes would increase their exposure to train noise and diesel pollution. They also said they're worried about flooding and the removal of trees that grow on and beside the embankment.

According to the Block Club report, neighbors had previously asked Metra to use an alternative bridge replacement method called "rolling in the bridge." This would involving building the new spans next to the existing ones and installing them during service shutdowns. But that approach require shutting off UP-N service on multiple days and delays at each bridge location, as well as increasing the cost and length of the project, Metra spokesperson Michael Gillis told Block Club.

But at Wednesday's meeting, the residents maintained that a few years of inconvenience for thousands of Metra riders was less important than the permanent impacts to their properties caused by the change in track location.

They asked the commuter railroad on why they couldn’t replace each bridge all at once, instead of one bay at a time, pointing to the South Shore Line’s 130th/Torrence bridge replacement as an example of how it could be done. Justin Pattison, the engineer for the project, said the South Shore Line had much more room to work with in that industrial section of Hegewisch than they will in denser, mostly residential Lakeview.

Steve Hands, the environmental consultant for the project, said that, under the current safety standards, the railroad tracks need to be built further apart than they did when the line was originally elevated.

Several residents complained the project will lower their property values and hurt their community. Ahmed Naguib, who has lived at Picardy Place for the past four years, said that, after the original west track was removed, much of the industry around the embankment gave way to residences. “We’ve been growing, gentrifying, changing the North Side, and you’re endangering everything we have done,” he said.

As the meeting wound down, residents pressed the project staff to commit to holding another town hall. Sullivan said that they didn’t have the authority to do that. “This is outside the scope of our current consulting contract. I don’t have the authority to change the contract unilaterally.”

More thoughts from residents

My interviews with the residents who pushed for a town hall revealed certain patterns. Most or all of them moved to their current homes over the last few years, and even the ones who have been there longer moved in long after the original west track was removed. A significant portion of them live in Picardy Place.

Craig Gunderson, a Picardy Place resident of three years, complained that project would turn his back yard into a “trench,” increase train noise and “rip up the green space." He added, "I would like to see [Metra and U.P.] use this space with more consideration. I don’t believe they need to come as far west as they [believe they] do.”

Metra didn’t describe the format for last week's meeting in detail in advance on either the event registration page or the project page. Neighbor Christie Calmeyn told me residents have been demanding a town hall since the September hearing, but Metra declined to hold one. She added that the vague wording of the info preceding last week's event gave them hope that the commuter railroad might hold a town hall. "We were not surprised – we were more disappointed” with the actual format, she said.

Calmeyn told me she and her husband bought their century-old home on Barry Avenue (3100 N.), just west of the UP-N, specifically so their children would have a space to play. “Over 150 homes are impacted by this, and we all have children, and we all have pets. We have a tree that’s 50 years old that’s on our property, and our arborist told us they’re going to tear it down.”

Out of all the residents I interviewed, only Calmeyn told me she uses the Union Pacific North line, saying she takes it to see her brother in the North Shore suburb of Wilmette. She argued Metra would be better off reallocating the money from this project to convert locomotives from diesel to hybrid. But even if it wasn't necessary to replace the 120-year-old bridges, which it is, the $156.1 million earmarked for the project from the Rebuild Illinois state infrastructure bill couldn't be used for locomotive conversion, because that funding was specifically appropriated to replace bridges.

After the meeting, Barrie struck a conciliatory tone, saying that she hopes that Metra will work with neighbors on a compromise, and that “Metra can be a good partner and not destroy property and ecosystems.”