Who should we really be building bikeways for?

12:20 AM CST on January 10, 2022

A raised bike lane on Commonwealth Avenue near Boston College. A facility like this can encourage “normal” people to bike. Photo: John Greenfield

Last week I wondered aloud on Twitter, why do so many experienced, confident urban cyclists seem to despise non-protected lanes striped to the left of the parking lane, aka "door zone lanes"?

The question occurred to me after a fellow cycling advocate stated on Twitter that the bike lanes on Chicago's Roosevelt Road between State and Canal Streets south of downtown are pretty awful, since they're sandwiched between two lanes of fast-moving traffic, but "at least [they're] not a door zone [lanes]." He proposed, sensibly enough, that the bike lane should be moved to the curb lane (where I ride on this stretch anyway), since there's no parking on this segment of Roosevelt.

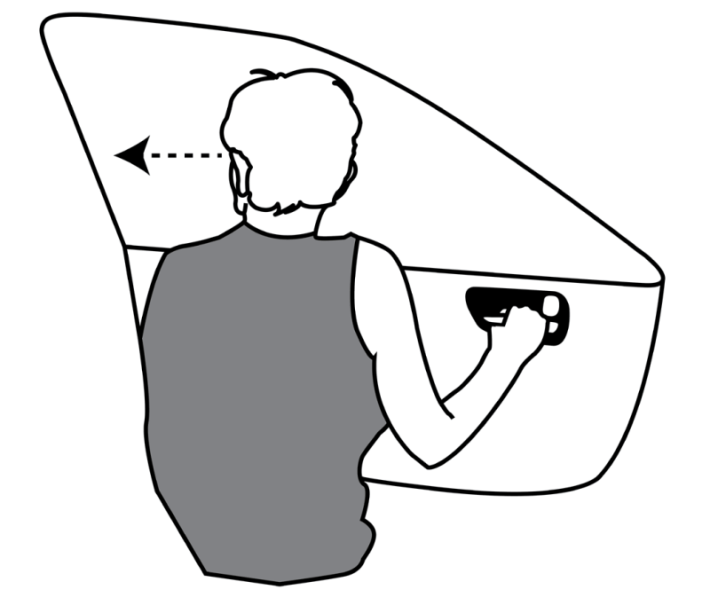

But why all the hate for door zone lanes? As the nickname suggests, when people enter or exit parked cars to the right of these kinds of lanes, the open door may occupy part of the lane, creating the risk that a cyclist may strike it, with potentially tragic results. Motorists, you should always do a move called the Dutch reach, opening the car door with your opposite hand, which encourages you to check over your shoulder for people on bikes.

However, unless a driver is flinging their door open at full force, I think it's actually pretty easy to avoid getting doored in a door zone lane. Assuming you're biking at, say, 15 mph or less, if you ride in the left-most portion of the bike lane, you should have plenty of time to react to a motorist opening their door by looking behind you for traffic and merging into the mixed-traffic lane, or else hitting the brakes. That's if it is necessary to get out of the way at all – depending on how wide the the bike lane is, if you're riding in the left-most portion, an open door may not even block your path.

If you really like to haul ass on a bike, such that you'd have less reaction time, ride in the middle of the adjacent mixed-traffic lane instead, aka "taking the lane," and you shouldn't have a problem keeping up with motor vehicle traffic. (I'm bracing myself for angry comments from followers of the late "vehicular" cycling guru John Forester, who will surely argue that bike lanes are bad because they supposedly contribute to driver rage against cyclists who don't use them.)

I credit my door zone riding technique with the fact that, after riding a bike in Chicago nearly every day for about 30 years at moderate speeds, I've never crashed or been injured by someone opening a car door in my path from the parking lane. (On one occasion I crashed and "taco-ed" a wheel when a taxi driver pulled up to my left and the customer opened a passenger-side door in my path.)

So I was puzzled why similarly seasoned cyclists have such fear and loathing of door zone lanes. And, in their defense, DZLs are relatively cheap and low-maintenance – debris and snow clearance aren't nearly as much of an issue as with curbside lanes – and they're politically easier to install because, unlike protected lanes, they often don't require converting mixed-traffic lanes or stripping parking.

But, on further reflection, I was asking a pointless question. I'm totally fine with riding in door zone lanes on main streets (although I prefer quiet side-street routes), and some of you may agree with me. But if our aim is to use transportation cycling to reduce crashes, pollution, and congestion, and improve health and economic outcomes for residents, we need to make it mainstream travel mode. And the preferences of confident, experienced city cyclists like me (I worked as a bike messenger for years) aren't important at all for achieving that goal.

Door zone lanes are relatively useless for encouraging "normal" people – non-enthusiasts who don't currently bike for transportation – to ride in cities, because they don't feel safe or comfortable to them. For many everyday Chicagoans, the idea of riding a bike with no physical protection from moving motor vehicles, or where there's any possibility that someone might open a car door in their path, is a total non-starter. They have zero interest in exposing themselves to those perceived risks. That might be particularly true for women and people of color, some of whom say their gender and/or race may contribute to an increased risk of harassment from motorists.

That's why to exponentially increase Chicago's bike mode-share, currently only 1.7 percent of work commuters, which is what's needed to fight climate change and reap many other societal benefits, we need a citywide network of connected, protected bike lanes and off-street trails. Those kinds of facilities appeal to regular folks who may be interested in cycling, but aren't willing to use non-protected on-street bikeways. Families with young children and seniors often fit into that category.

But to make that mode-shift happen, we've got to increase not only the quantity, but also the quality of Chicago's protected bike lanes. The current standard of curbside lanes, often on sloping, potholed pavement, separated from the parking lane or moving cars by flimsy plastic poles, and frequently filled with water, debris or snow, or blocked by illegally parked cars, isn't going to cut it.

At the very least, we need to switch the default for bike lane protection from flexible posts to sturdy concrete curbs or other barriers that keep cars out of them. Better yet, let's improve the pavement quality and drainage of the bikeways by making raised bike lanes the new Chicago standard, as it already is in international cities with exponentially higher mode shares than ours. The city also needs to prioritize maintenance of the lanes so that, for example cyclists can expect that as soon as main roads are clear of snow, the bikeways will be too (or even earlier.)

Lastly, it would be great if more of the people advocating for bikeways weren't folks like me who already ride daily, but rather non-enthusiasts saying, "I'd like to bike commute, but I don't want to ride next to moving traffic. Let's build a protected bike lane network so people like me can do that." I'm talking about folks like Active Transportation Alliance campaign organizer W. Robert Schultz III, who responded to this idea on Twitter:

that's me!

— W Robert Schultz III (@Socialistdrums) January 7, 2022

That would be really helpful for building the political will we need to make the vision of truly bike-friendly U.S. cities a reality.

In addition to editing Streetsblog Chicago, John writes about transportation and other topics for additional local publications. A Chicagoan since 1989, he enjoys exploring the city on foot, bike, bus, and 'L' train.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Chicago

Today’s Headlines for Thursday, April 25

It’s electric! New Divvy stations will be able to charge docked e-bikes, scooters when they’re connected to the power grid

The new stations are supposed to be easier to use and more environmentally friendly than old-school stations.