Read the article citations here.

E-scooters launched unexpectedly in the United States in the fall of 2017, wreaking havoc on many unsuspecting city residents and offering a novel new transportation option to others. Cities were forced to spring into action and formulate the best way to respond to this new mobility option. Policymakers ran the gamut on this new disruptive technology by banning it, regulating it, and/or collaborating with the e-scooter companies (Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 2021; Zipper, 2020).

The question is, after five years, how have the e-scooters measured up? Have the e-scooter companies delivered on all their promises and cleaned up their acts? We asked a few Chicago mobility leaders and their answer is: yes and no.

City Collaboration

When e-scooters first launched, they did so by "asking for forgiveness," as opposed to "asking for permission" by following the proper bureaucratic steps and acquiring the proper permits. Many companies launched their scooters in cities without any advance notice or the green light from city officials. E-scooters have been banned from cities all over the world and received many cease and desist letters (see the map below for a few examples). Some cities banned them preemptively after seeing chaos in other cities, some tolerated the surprise drops for a while, and then eventually cracked down.

Have cities opened up to the idea of e-scooters? Yes. ”E-scooters have become indispensable to many urbanites,” according to Dr. Joe Schwieterman, director of DePaul University’s Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development. “They fill a niche on trips too long to walk but awkward for public transit or driving.” In addition, cities have become more adept at dealing with scooter companies that want to launch after learning from other municipal policies. Cities like Chicago and Santa Monica have launched e-scooter pilot programs that have shown a fair amount of promise. That said, both cities required companies to remove their scooters following the conclusion of their pilots (Harter, 2021).

An upward mobility study by Harvard in 2015 found the most important factor in escaping poverty to be commuting time. The longer an average commute, the worse the chances of low-income workers escaping poverty. Micro-mobility options, like e-scooter sharing programs, can help in shortening commuting time for these underserved populations. E-scooter companies have promised their mobility option will help fill many of the mobility gaps cities lack resources to fill (Zhou, 2020).

Cities have put these companies to the test as there have been a variety of e-scooter equity policies adopted across the country with policies that include language accessibility (e.g. Washington D.C., San Francisco, and Portland), cash payment options (e.g. Kansas and San Francisco), non-smartphone access (e.g. D.C.), and equitable hiring practices (e.g. Portland). Some cities, like St. Louis, Missouri and Chicago, have required e-scooter companies to place vehicles in designated “equity zones” to aid underserved communities that lack transportation options.

Chicago's 2020 pilot also had an “equity priority area” that required operators to have 50 percent of their vehicles available on the city’s South and West sides. Although the pilot’s equity priority area was about half of the pilot area, only 23 percent of scooter trips in the pilot originated there. 23 percent may have been a smaller percentage than the city of Chicago had hoped to see. However, the pilot was still successful in offering residents a mobility option they did not have access to prior to the pilot (Center for Neighborhood Technology, 2020; Plautz, 2021).

E-scooters show a lot of promise with solving issues in transportation deserts by providing complementary services. “E-scooters are not going anywhere,” according to Elizabeth Kocs, director of partnerships and strategy at UIC Energy Initiative. “What cities and public transit [need to do are] find ways to embrace and incentivize e-scooter usage where it is most needed, such as where public transit gaps exist and where first and last mile challenges remain unresolved.”

But that’s only half the battle. According to Oboi Reed, CEO of the Chicago-based mobility justice nonprofit Equiticity, if cities want to increase ridership in equity areas they need to “invest in community-led micromobility models such as neighborhood-based mobility hubs, non profit operators, and other innovative strategies that prioritize racial equity and mobility justice over profit.”

Clutter and mobility

Cities are still trying to manage the cleanliness of their e-scooter programs. In fact, the issues of aesthetics have led some cities, like Greenville, South Carolina, to hold off on allowing e-scooters to launch in their city. Story after story has been shared of e-scooters scattered across sidewalks, limiting access for citizens that rely on wheelchairs or other devices.

Has e-scooter clutter and vandalism gotten better or worse since 2017? It’s hard to say. COVID-19 most likely reduced e-scooter use, as many users were sheltering at home rather than commuting to offices (Cobbs, 2021). As a result, there were not as many people out and about using any kind of shared mobility.

There has been progress by cities like Chicago and D.C. that have enacted “lock to” requirements, which mandating that scooters be secured to bike racks, sign posts, or light poles via built-in cable locks (Nabizad, 2021; Spielman, 2021). Chicago Department of Transportation assistant commissioner Sean Wiedel said he believes that “the ‘lock to’ requirement helped reduce sidewalk clutter” in Chicago. That said, the “lock to” requirement is not viable in cities that lack bike parking infrastructure. Chicago, however, “currently has more than 15,000 racks, likely the most of any U.S. city,” according to John Greenfield of Streetblog Chicago (2018).

Safety

Cities around the world have been shaken from e-scooter injuries and deaths. There have been reports of riders being sent to the hospital with ailments ranging from broken bones to traumatic brain injuries. According to , Chicago's 2020 pilot had, “171 probable emergency department visits due to e-scooter incidents… compared to 192 in the 2019 pilot.” This reflects the fact that ridership dropped during the pandemic, despite the fact that more scooters were available, and the service area was expanded.

Meanwhile, e-scooter injuries nationally were on the rise nationally, as of June 15, 2021 (Krauth, 2021). Physicians are even sounding the alarm on the rising number of injuries caused from riding electric scooters, calling it “a growing public health concern” (Nisson, et. al., 2020). In a study of e-scooter injuries, Kathleen Yaremchuk, M.D., chair of the Department of Otolaryngology — Head and Neck Surgery, reported that head and neck injuries made up 28 percent of the total scooter injuries (ENT E-scooters Study, 2020).

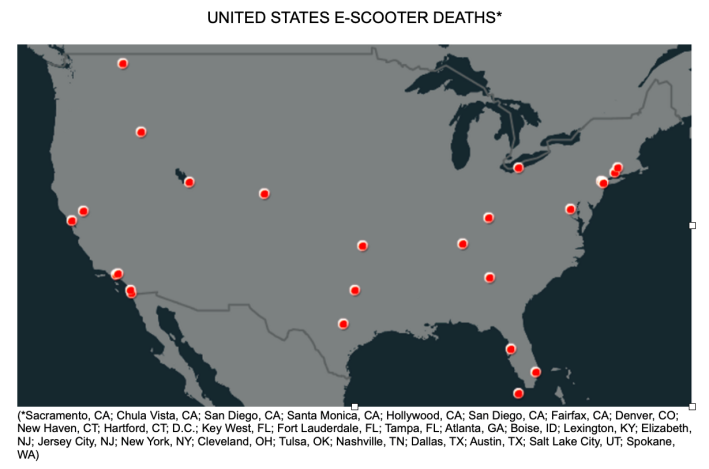

There have also been multiple fatal scooter crashes. For example, n 2018 in Washington D.C., an e-scooter rider was hit by an SUV driver while riding, pinned beneath a car and dragged 20 feet to his death. In Austin in 2019 an e-scooter rider was hit by a car driver while riding the wrong direction on a road and killed. In Tulsa in 2019, a mother and child were riding a single scooter together when the mother rode into oncoming traffic, at which point the child fell off the scooter and was struck by a car driver and killed (E-Scooter Fatalities, 2021).

The main causes for these deaths? Insufficient infrastructure, improper speed limits, lack of helmets, and opaque or insufficient rules. According to one study, 80 percent of e-scooter fatalities in the U.S. were caused by drivers of cars (Cherry, 2021). In short, putting e-scooter riders on the same roads as cars without adequate infrastructure has been disastrous. Creating safer streets will require policymakers to understand where and why drivers collide with riders of these new vehicles.

But unsafe streets are just part of the problem. The other problem: the sidewalk.

A study by Shah, et al., points to riding on the sidewalk as the main risk factor of e-scooters. Despite local rules prohibiting scooter-riding on sidewalks, more than 60 percent of crashes between cars and scooters happened when a a person riding a scooter on a sidewalk and driver collided at either a driveway or a crosswalk. The scooter rider was almost always traveling on the motorist's right side, where turning drivers likely aren’t expecting moving vehicles to come off the sidewalk and into traffic (Cherry, 2021). The scooter company Bird has developed a sidewalk detection tech that could help this problem.

Sustainability

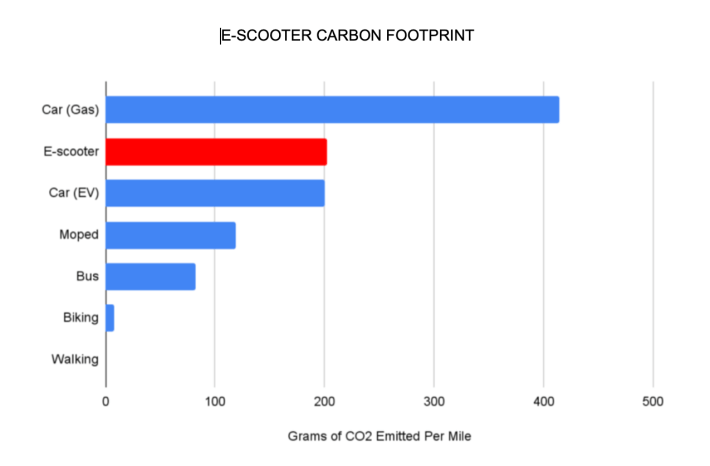

One of the benefits touted by e-scooter companies is that their rides are completely “carbon free” (Rosen, 2021). Companies made big promises to help cities hit their climate action plan goals by offering a mobility option that releases less C02 in the air than driving. But the truth is a lot more complicated than that.

Although traveling a mile via scooter may be better for the environment than driving by car, it’s worse than biking, walking or taking a bus. This is due to the energy-intensive materials that go into making e-scooters, and because of the driving required to collect, charge, and redistribute e-scooters. CDOT’s Sean Wiedel was succinct in his response pertaining to sustainability and e-scooters: “We did not see a lot of progress on operational sustainability during the scooter pilot.” Sure the e-scooters themselves don’t emit Co2; However, the energy that goes into building them, charging them, and distributing them all over a city adds up (Rosen, 2021).

There’s also the issue of e-scooter longevity. E-scooters must not only survive the everyday wear and tear of riding and recharging, but also rampant vandalism of non-"lock to" vehicles. People are still trashing e-scooters in cities across the world. Scooters have been burned, broken, tossed into the ocean, and thrown into trees (Newberry, 2018; Ho, 2018). Why do they do it? They do it for fun, and out of the belief that these vehicles and the tech start-ups behind them are encroaching on public space.

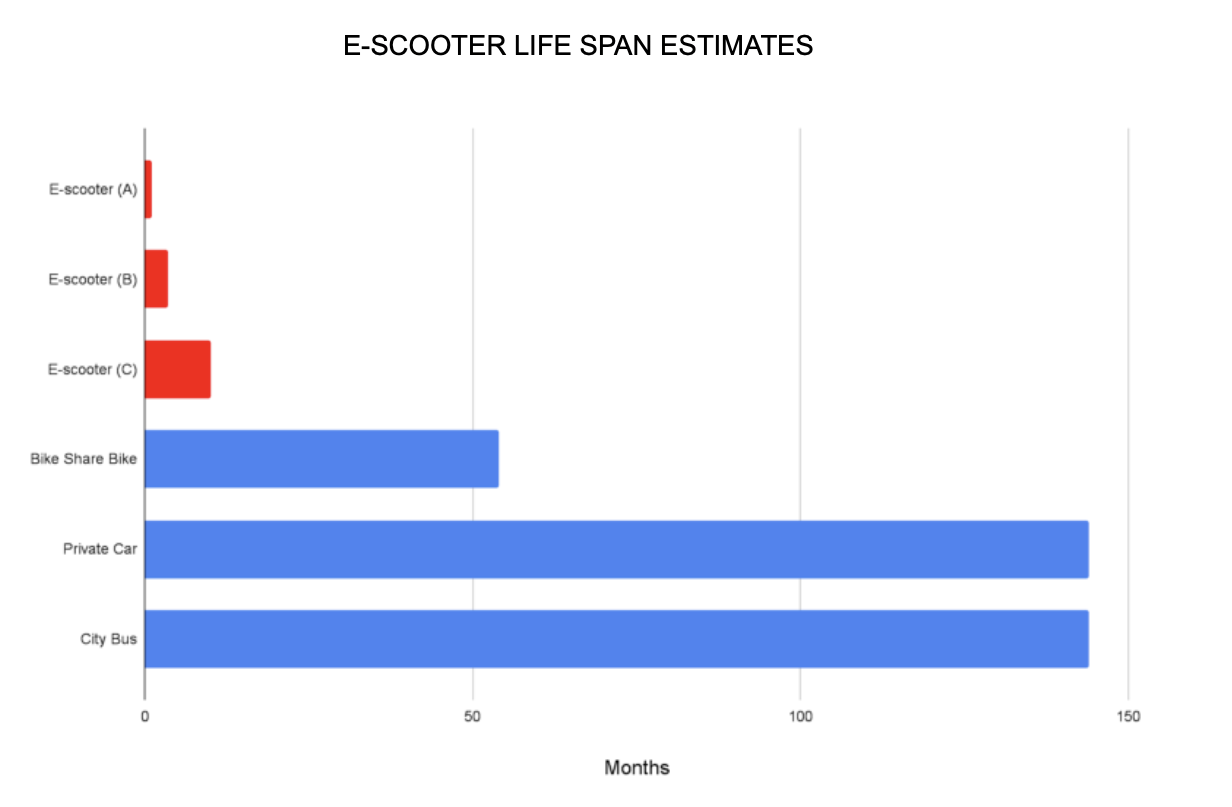

There have been several studies on e-scooter lifespan, and these studies have alternately found that e-scooters have a shelf life of less than one month (29 days)(Griswold, 2019 — A), three to four months (Rosen, 2021 — B), and 10 months (Hawkins, 2019 — C). In contrast, bike-share cycles, like D.C.'s Capital Bikeshare, have an average lifespan of 4.5 years (Sussman, 2018), while private vehicles and city buses on the other hand have an average shelf life of 12 years (Demuro , 2019; MacKechnie, 2019).

If a scooters’ lifecycles are that short, that means their impact on the environment is even more deleterious than originally predicted, due to materials and manufacturing. Matt Chester, an energy analyst at Chester Energy and Policy put it plainly “even when we’re generous [about scooter lifespans], it still looks pretty bad” (Chester, 2020).

Scooter companies have started deploying scooter models that are sturdier and more durable in the hopes that they will last more than a year (e.g., Lyft’s partnership with Segway). No word yet on the statistics or progress of that new venture (Dickey, 2019; Hawkins, 2019).

Based on estimates, the nightly collection and redistribution of scooters accounted for 43 percent of their overall global warming impact. Researchers found that while riding a gas-powered car for one mile emits 414 grams of CO2, an e-scooter isn’t far behind with 202 grams of CO2 emitted per mile, slightly higher than an electric vehicle with 200 grams of CO2 (Choudhury, 2021). Even a gas-powered moped (119 grams) and bus (82 grams) emit less CO2 per mile than an e-scooter. Biking and walking are the most sustainable modes of transportation with 8 and 0 grams emitted respectively (Rosen, 2021). In short, e-scooters aren’t the sustainable heroes they’re claimed to be.

Companies have started building more durable products, purchasing clean energy or carbon offsets to compensate for the emissions associated with charging their scooters, as well as making promises to at least phase out gas-powered vehicle use for collection/redistribution (Lime, 2020; Bird, 2019). But they’ve got a long way to go.

Complementing transit

A study by Yan, et al., (2021) focused on e-scooter use patterns in relation to D.C.’s Capital Bikeshare and Metro transit system and found that between 8 to 12 percent of all e-scooter trips were taken to connect with Metrorail before COVID-19. However, trips on e-scooters during the pandemic may have replaced public transportation rides. The researchers found that in places where e-scooters overlapped with transit and bike-share, more than 90 percent of scooter trips could have been made by Metro or CaBi (Yan, 2021).

Results from another study revealed 31 percent of users chose e-scooters over active transportation (e.g., walking) (Carey, 2021). A separate study reviewed that roughly 27 percent of e-scooter trips could potentially compete with the bus system in Indianapolis, Indiana. And the competition could lead to a bus ridership reduction (Luo, 2021). Kate Lowe, associate professor of urban planning and policy at UIC, says, "cities should be careful of the policy attention and resources devoted to e-scooters when other less flashy solutions, like quality sidewalks and bus investment, are often more critical for the environment and equity.”

We have yet to see the promise of e-scooters fully realized. Scooters have brought a lot of good to city life, in part because they have made people rethink how they travel. Prior to this new technology, many people who might have previously felt stuck with driving their own vehicles may now take a minute to think about the plethora of mobility options available to help them get to where they need to go. E-scooters have forced us to talk about sustainable transportation, what that means, and what our goals should be.

There has been progress with city collaboration, equity, and clutter and vandalism. City collaboration has come a long way with fewer cities banning e-scooters, and more that are open to piloting them. Advances in equity have been shown via equity priority areas. Clutter and vandalism are still issues; However, "lock to" requirements have had positive results.

There is still a lot of work that needs to be done when it comes to safety, sustainability, and complimenting transit. As for safety, e-scooter injuries are still on the rise, which may reflect increased ridership. Although several scooter companies have made attempts to make their companies and products more sustainable, the fact still remains that rebalancing them adds to congestion and releases large amounts of Co2 into the air. Finally, e-scooters companies have long touted their products' potential to complement transit, but several studies have shown this micro-mobility option might instead be replacing existing transit or walking trips.

Micro-mobility has come a long way, but scooter companies still have work to do.

About the authors

Brandon Bordenkircher, was the General Manager for car2go in Chicago and is currently vice president of business development at Innova EV, an electric vehicle car-share company. Riley O’Neil, was part of the founding team and the head of operations at shared scooter company Ridy and currently manages the CDOT Bike Parking Program, arranging the installation of thousands of bike racks throughout Chicago.