About four months after the Chicago City Council overwhelmingly voted to rename Lake Shore Drive after Black city founder Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, officials and activists unveiled the first street signs today at a ceremony at Buckingham Fountain. Speakers hailed the name change, which makes the shoreline highway the first street in Chicago named after a Black person that spans both the South and North sides, as a step in the right direction towards acknowledging the contributions of people of color in building our city.

Tomorrow the Chicago Department of Transportation will start installing the 12 large highway and over 80 smaller street signs along the roadway from Hayes Drive in South Shore to Hollywood Avenue in Edgewater. According to a city staffer, due to a shortage of steel and other supplies, the rest of the signs will need to be added in the future. CDOT estimates its total cost at $500,000. The Illinois Department of Transportation will also change expressway signs, and the CTA will also be updating signs and other materials.

DuSable, traditionally said to have been born in Haiti, was a trading post operator who, along with his Potawatomi wife Kitihawa, established the first recorded permanent settlement in the Chicago area in the late 1700s, which eventually grew into our current metropolis.

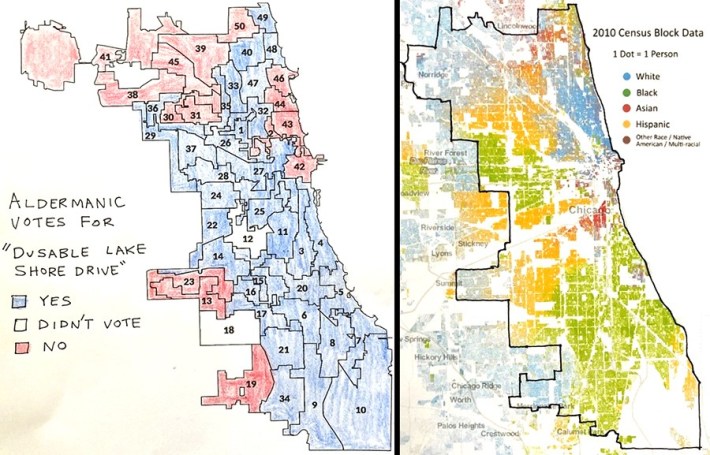

In the wake of last year’s police murder of George Floyd, the advocacy group Black Heroes Matter, along with African-American aldermen David Moore (17th), the "DuSable Drive" ordinance sponsor, and cosponsor Sophia King (4th) argued that it would be a powerful statement of pro-Blackness to rename the drive for the pioneer. However, there was fierce opposition to the proposal, largely split on racial lines. Black mayor Lori Lightfoot also opposed the plan, arguing that to jettisoning the "Lake Shore Drive" name would hurt Chicago's brand.

Downtown aldermen Brian Hopkins (2nd) and Brendan Reilly (42nd) even spent $12,000 in campaign funds on a survey in an effort to prove that most residents were opposed to renaming the drive. The poll instead showed that a majority of Chicagoans didn't have a problem with the name change. It also quantified the racial divide, finding that Latinos were 28 percent more likely to be in favor of renaming Lake Shore than whites were, and African Americans were nearly twice as likely.

Ultimately the proposal was changed to the rather wordy compromise name "Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable Lake Shore Drive." (There are various ways of spelling and punctuating DuSable's name.) 33 of the 48 aldermen voted for the name change. Of the 15 naysaying aldermen, none were Black, and 12 were white, representing two-thirds of the city’s white aldermen. While Lightfoot had the option of vetoing the ordinance, she chose not to, indicating that she was satisfied with the compromise, or at least wasn't willing to risk awkward optics from blocking the measure.

During today's event the mayor promised that, despite the renaming, she will follow through with her $40 million counterproposal to the measure, including the development of DuSable Park, a hump of land near Navy Pier; renaming the Chicago Riverwalk for DuSable, whose trading post was located on the north bank of waterway near present-day Michigan Avenue; launching an annual DuSable Festival; and installing three statues of the city founder.

"Those plans are in place, pending the approval of the various budgetary items by the City Council," Lightfoot said. "We've got most of the money for the park and some of that work is already starting... It is really important that people in the city know our history, and an important part of that history is understanding the significance of DuSable." She added that the Chicago Park District and the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events has a plan to use the riverwalk as a gathering place for tours and educational seminars. "There a lot of good that will come from this, but not the least of which is DuSable's name will never be forgotten in Chicago again."

Several of the speakers credited Black Heroes Matter leader Ephraim Martin for tireless advocacy on the issue, since he testified at virtually every meeting and public hearing. Martin told the crowd that he first heard about DuSable years ago from then-Congressional rep Harold Washington, who went on to become Chicago's first Black mayor, while Martin was a reporter for the Chicago Defender newspaper. "Following the death of George Floyd, we said enough is enough and joined forces with aldermen Moore and King to make sure that we fought and would never back down until [we achieved] victory for the founding father of this great city."

Moore told me that he thinks highlighting the fact that Chicago was founded by a Black person will give hope to local children and promote unity among adults. "That's what DuSable was about. He was about bringing people together at his trading post. That's why it was important that the whole drive was renamed: It's bringing the whole city together, not just one part."

King said that DuSable being elevated to his proper level of recognition brought her "joy." As for the arguments that the name change would damage Chicago's international reputation, she said, "the sky didn't fall. Part of that is ignorance. I think it was a journey for everyone, including our mayor, to get here."

King worked with Alderman Reilly a few years ago to get Congress Parkway renamed to honor Chicagoan Ida B. Wells, an investigative journalist, anti-lynching activist, and suffragist. Asked whether she thinks Reilly and Hopkins have come around on the Lake Shore Drive rename, she said she hasn't discussed the matter with them since the June Council vote. "But I do hope that, like others have come around, they now see that this is how our founder should be celebrated... It's not only worth it, but long overdue."

Another fight regarding the coastal highway is on the horizon, as the city and state prepare to reconstruct North DuSable Lake Shore Drive. Transportation advocates are arguing that, at a minimum, two of the eight lanes should be converted to bus-only corridors. Some are saying we should go further by radically transforming the roadway into a four-lane surface boulevard with bus rapid transit and a new commuter bikeway, which would help fight climate change and reconnect the city with the lakefront.