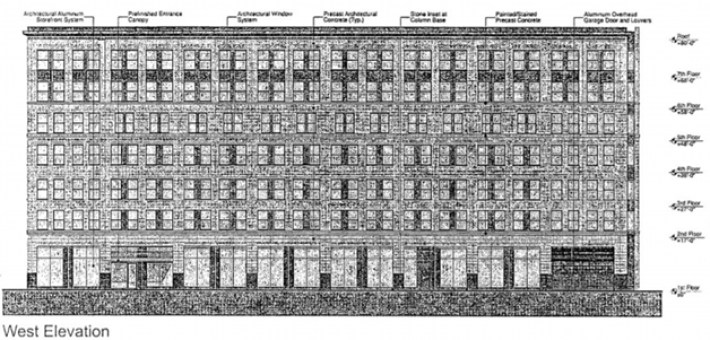

Image above: Rendering of the first phase of 901 Halsted Point on Goose Island, one of the developments approved at September’s City Council Meeting.

September’s City Council meeting approved zoning changes that will create a significant amount of affordable housing, including units at several transit-oriented developments. In total, the council approved zoning changes permitting approximately 6,074 new housing units, including 760 units that are required to be affordable. But while the approvals represent important steps forward, they also highlight just how far Chicago must go to address the city’s affordable housing shortage.

For the purpose of these approvals, there are two important pieces of legislation that help support affordable housing production. The first is the City’s Transit-Oriented Demand Ordinance. Since 2015, the ordinance has loosened development restrictions within a quarter mile of train stations and selected high-frequency bus corridors. Those include up to a 33 percent increase in the number of dwelling units, and essentially waiving the usual off-street parking requirements.

In addition, any zoning change, including a project that qualifies as a transit-oriented development, is subject to the city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance. In September, when the zoning changes for the following developments were approved, this required least 10 percent of apartments in rental buildings with more than 10 units to be affordable to individuals making 60 percent of the Chicago region's area median income. That comes out to $1,100-$1,200 per month for a two-bedroom unit. While at least a quarter of those affordable units had to be located on-site, developers have historically had the option of covering the rest of their affordable housing commitment by paying in-lieu fees that the city uses to support other affordable housing developments in the city.

Unsurprisingly, those in-lieu fees have attracted significant controversy. While they may allow for additional affordable units to be built in other neighborhoods, they also allow developers to avoid renting to residents of various income levels.

However, revisions that strengthened the ARO kicked in on October 1. The ordinance now requires 20-percent affordable set-asides in high-cost neighborhoods, and increases the portion of affordable units that must be provided onsite from one-quarter to one-half. And recognizing that the 60-percent AMI threshold can still render "affordable" units out of reach for many residents, the new rules will also encourage developers to produce ARO units that are affordable to people at lower income levels.

So let’s see how these ordinances played out in regards to some of the developments approved last month:

Image above: The proposed development at 835-861 E. 63rd St.

835-861 E. 63rd St.: Steps from the Cottage Grove Green Line station, this 56-unit development will include 41 affordable apartments and 32 parking spots. The developers plan to exceed the requirements of the ARO (and a more stringent local displacement ordinance) with financing from low-income housing tax credits. In addition to directly addressing housing needs, the development is part of a broader set of complementary investments in the area, including a Jewel-Osco and the new headquarters for Friend Health.

Image above: The 901 N. Halsted St. development is set to include new bike trails and integrate with Chicago’s ‘wild mile’ along the river.

901 N Halsted: This mega-development on Goose Island will create 2,650 dwelling units including 530 affordable apartments, along with 300 hotel rooms. While the project is roughly a half-mile north of the nearest 'L' station the Grand Blue Line stop, it will include relatively limited parking (1,400 units, or roughly 1 for every two units). The development will also offer 700 bike storage spots, eliminate on-street parking, and include new bike trails around the site.

Image above: rendering of 547 W. Oak St. Source: Pappageorge Haymes Architecture via Chicago YIMBY.

547 W. Oak St.: Currently a lot owned by the Chicago Housing Authority as part of the Cabrini-Green site, this development will create 78 new units, 39 of which will be affordable. It qualifies as a transit-oriented development thanks to the nearby high-frequency Chicago Avenue bus route, which is why the developer isn't required to provide the usual 1:1 car parking ratio.

These developments represent important progress. ARO-required affordable units can directly help reduce displacement. At the same time a larger supply of market units, especially in expensive neighborhoods, will help soak up housing demand that would otherwise bid up prices elsewhere in the city. Finally, new development near transit can help ensure a stronger post-pandemic recovery in CTA ridership.

One step forward, two steps back

But while the developments mentioned above can help address important needs, the pace of approvals also highlight just how inadequate Chicago’s current planning approach is. Some simple math makes this clear. As of last year, the Chicago Department of Housing calculated that the city had an affordable housing shortage of almost 120,000 units. Even if those 760 new affordable units were built today, it would take 13 years of equally productive monthly meetings to close the gap. And sadly, because the ARO production numbers have historically been much lower than the 760 new units approved last month, the housing department forecasts that across all programs this year the city will only create or preserve 5,787 affordable units. At that rate, it would take more than 20 years to close the affordability gap.

And even this calculation dramatically underestimates the city’s affordable housing crunch. According to new research from DePaul’s Institute of Housing Studies, as market rents rose the supply of units affordable to individuals at 150 percent of the poverty line fell by 5.2 percent between the periods of 2012-2014 and 2017-2019. Chicago can and should add funding to support the creation of more affordable units. But if more isn't done to prevent market-rate rents from rising so rapidly, the city’s affordable housing programs will have to run ever faster just to stay in place.

It’s clear that restrictive zoning on the North and Northwest sides that blocks the construction of larger apartment buildings and 2-4 flats is a key part of the story. As the DePaul study notes, the biggest decreases in the affordable unit supply were in fast-gentrifying Northwest Side neighborhoods like Logan Square and Portage Park. But the neighborhoods outside of the Loop with the lowest share of affordable units are in areas further east such as Lakeview, Lincoln Park, Lincoln Square, and North Center, which have made it progressively harder to build new apartment buildings and pushed renters further west. This reflects a consistent pattern: When neighborhoods become more desirable but new apartments can’t be built, rents rise and displacement accelerates.

Structural problems need structural solutions

Each additional affordable unit approved by the Council represents progress over the alternative. But rather than simply fighting a rearguard action as prices rise, Chicago needs to both produce affordable units faster and change the underlying conditions that are driving rent increases across the city. That opportunity exists. We Will Chicago, the city’s first effort to update its comprehensive plan since 1966, presents a chance to reverse some of the down-zonings that have contributed to rising market rents. An updated, comprehensive effort to boost affordability, housing supply, and equitable transit-oriented development would have a much better shot at holding down rents and halting displacement across the city.