A consultant by day, Richard Day (@richsday) serves on the board of Renaissance Social Services, an affordable housing provider in Chicago (the opinions expressed here are his own.) He lives in Logan Square and is on a mission to find the best hot dog in the city.

In the coming months, the City Council’s Zoning Committee has the chance to weigh in on a proposal that could change the future of affordable housing in Chicago. At first, the development in question, 8535 W. Higgins Rd. in the O'Hare community area, might seem like a slam dunk. A ten-minute walk from the Cumberland Blue Line Stop, the proposed 297-unit development would include 59 onsite affordable apartments, in keeping with the city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance.

According to the Metropolitan Planning Council’s TOD Calculator, a development at that size and location can be expected to support the CTA with over 53,000 transit trips a year, and generate $4.9 million in property and sales tax revenues over a ten-year period (note that the calculator is an estimate, and does not represent an MPC endorsement of the project.) And even the market-rate units would help reduce displacement pressure in other neighborhoods. No surprise then, that the project has been endorsed by the Chicago Federation of Labor, Chicagoland Chamber of Commerce, Neighbors for Affordable Housing, and the Chicago Plan Commission.

But one individual who hasn’t endorsed the development is the local alderman, Anthony Napolitano (41st.) And that’s what makes the Higgins Road development unique. Napolitano originally supported the development, but reversed course after neighbors objected to an affordable housing development in nearby Jefferson Park. In a 2018 letter to constituents about the Higgins Road development, he wrote that “Planned Developments (PDs), although beneficial to the city of Chicago, do not always have the best interests of our neighborhoods in mind,” and that “my priority as your alderman is to always advocate for your interests above else.”

Napolitano has said that he doesn’t object to affordable housing, but rather has concerns over school crowding, and is simply reflecting the wishes of his community that the area remained zoned for commercial uses. According to the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, a school impact study found that the proposal would add only 5 to 16 school aged children, and the Chicago Public Schools reports excess capacity in the region.

But if recent (and ancient) history is any guide, the Zoning Committee is almost certain to reject the application. That’s because the City Council has long defended the principle of aldermanic prerogative – the idea that aldermen have near-complete veto power over development proposals (among other things) within their wards. In return for being able to run their ward as an individual fiefdom, aldermen sacrifice their ability to influence developments across the rest of the city.

When the proposal came before the Z0ning Committee a month ago, only council and commission members Tom Tunney (44th) and Maria Hadden (49th) voted for it. The other 11 members (see if yours is on the list), all closed ranks behind Napolitano. Alderman Brendan Reilly (42nd) argued that it was “highly irregular” that the developer would even attempt to apply for a zoning change without Napolitano’s support.

A problem of local “costs" vs. citywide benefits

Local communities often have the best perspective on what should happen in their neighborhoods. And aldermen can be effective advocates for the priorities of the neighborhoods they represent. But as former 47th Ward alderman Ameya Pawar is quick to point out, a serious problem emerges when the perceived costs of a policy are local, but the benefits are citywide. “Local control matters, and it makes aldermen more responsive to the needs of their communities," he told me. "But local control over a citywide problem just empowers the mob.”

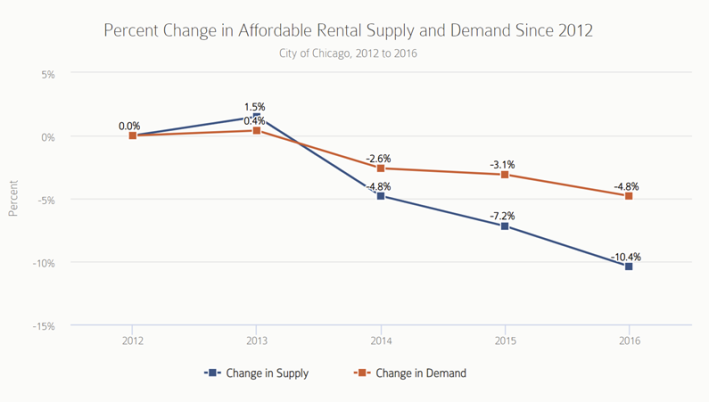

And projects like Higgins road are only the tip of the iceberg. Pawar notes that the barrier of aldermanic approval likely prevents many more projects from even being proposed. The requirement that aldermen sign off on the use of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, for example, can kill projects before they even secure financing. As a result, Chicago’s affordable housing shortage continues to worsen.

Not only does this set of local veto points reduce the amount of housing built in Chicago, it also influences where that housing gets built. When communities in wealthier, whiter areas want to block affordable housing, they know they can rely on their alderman to kybosh the project. As a result, instead of Chicago using affordable housing to help knit our city back together, our policies tend to force lower-income renters to live in lower-income communities of color. It’s no surprise that Chicago remains one of the most segregated cities in the country. As the Chicago Affordable Housing Alliance noted:

Aldermanic prerogative necessitates the continuation of the status quo, as aldermen rely on the preservation of neighborhood dynamics and demographics to secure their political longevity. Powerful and predominantly white neighborhood interest groups, in turn, have relied on aldermen to assist in the preservation of neighborhood racial makeup. This is historically rooted in a desire to explicitly restrict Black access to white neighborhoods.

Let’s strike a better balance between local input and citywide equity

There will always be tension between local control and centralized decision-making. But Chicago’s 120,000-unit affordable housing shortage is a critical emergency. Residents in every ward have an interest in more affordable housing units being built at Higgins Road (not to mention the millions of dollars in tax revenue.) But instead of other alderman sticking up for the interests of their ward on this issue, they’ve ceded their power to Napolitano. As this pattern plays out across the city, new affordable housing projects are shouted down by local residents who (often incorrectly) believe that they will face local "costs" from new developments, but only see a small share of the benefits they bring.

Fortunately, there are reforms that could preserve local influence while still allowing the city to build the housing it needs. Pawar suggests exempting approvals that include affordable housing from the purview of the Zoning Committee and City Council. Instead, zoning changes for developments that meet their full ARO requirement through on-site units, or are funded through Low Income Housing Tax Credits, could be approved by Chicago's housing commissioner, currently former Metropolitan Planning Council staffer Marisa Novara. While Pawar notes that that reform carries the risk that a future mayor could stall affordable housing production across the city, decision makers at the city level (including Novara), are generally much more likely to value the city-wide benefits of more affordable housing.

But even as legislation could solve this problem over the long run, aldermen on the Zoning Committee could send an important message in the short term. Approving the Higgins Road project would send the message that aldermanic prerogative isn’t ironclad. (After all, on her first day in office, Mayor Lori Lightfoot signed an executive order that supposedly eliminated aldermanic prerogative, but in reality did no such thing.)

It might even prompt other developers to come forward with similar proposals in other neighborhoods that have traditionally shunned affordable housing. Instead of entrenching segregation, a new set of developments just might help reconnect Chicago, strengthening the city’s affordable housing stock and tax base at the same time. Aldermen can decide to approve more affordable housing units and millions of dollars in future tax revenue. Or, they can continue to defer to the demands of a single alderman. Let’s hope they make the right choice.