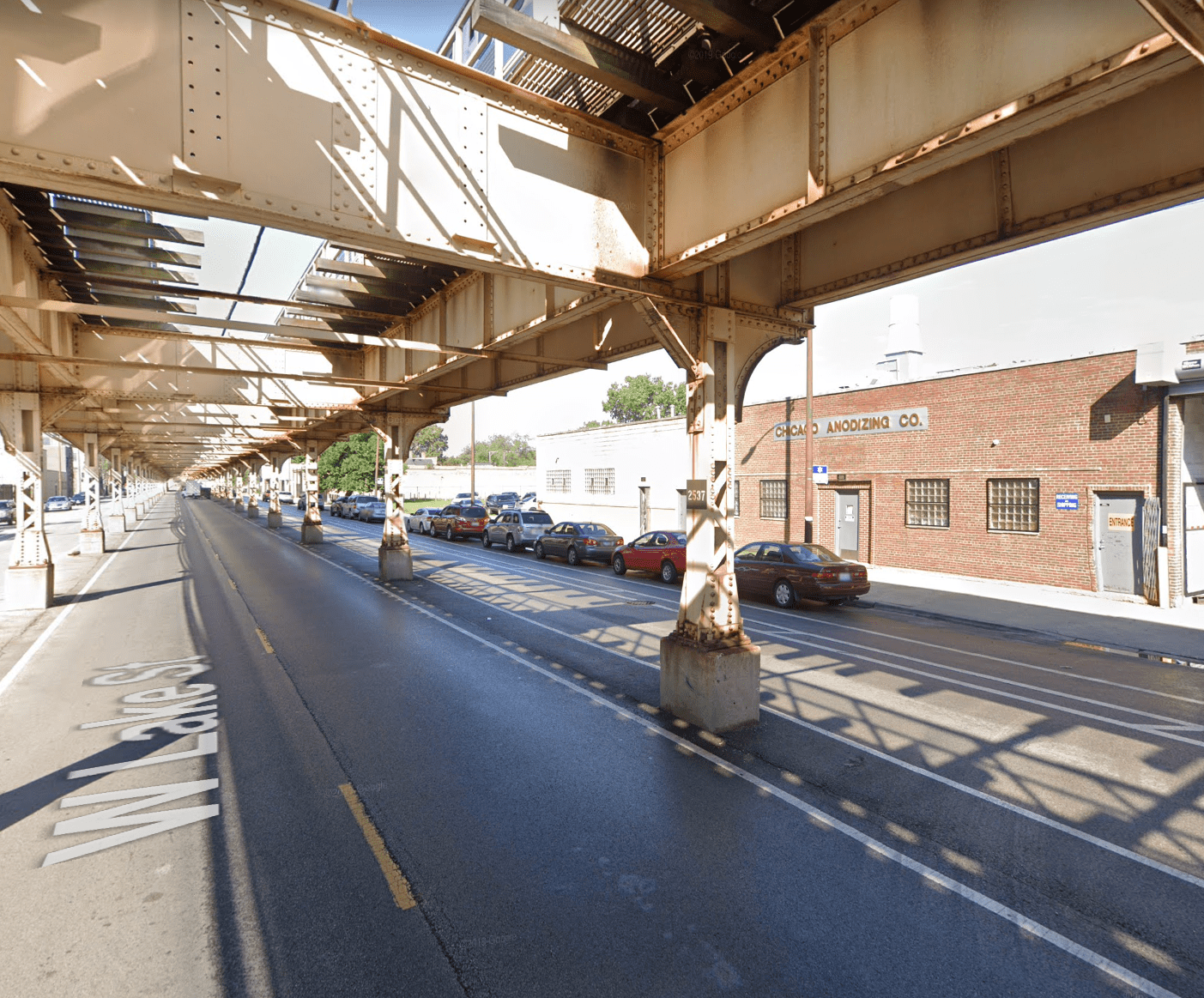

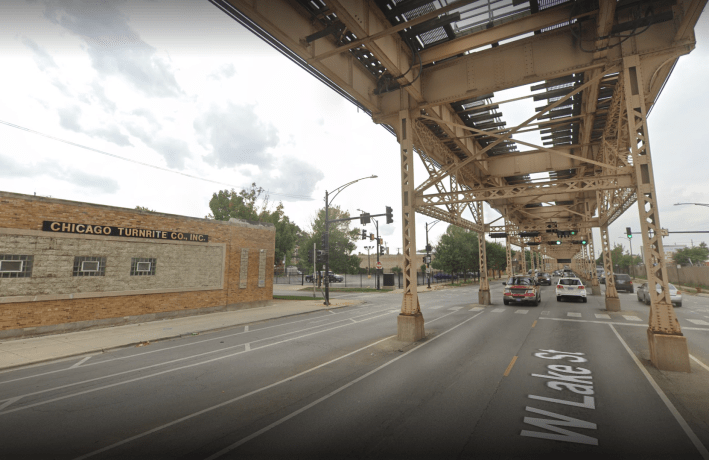

During a semi-public Zoom meeting on Tuesday hosted by Fulton Market Association director Roger Romanelli, Chicago Department of Transportation officials promised to look into the possibility of installing signs warning trucks drivers about low clearances under the Green Line ‘L’ tracks that run above Lake Street between Laramie (5200 W.) and Talman (2630 W.) avenues.

But even if CDOT does follow through with installing the signs, Romanelli made it clear during the meeting that he still wanted the CTA to use $1.8 billion of the roughly $15 billion Illinois expects to get from federal infrastructure bill to raise the elevated tracks and move the support columns to the sidewalk. He argued that this would revitalize the West Side and help industrial businesses located between Lake Street and Metra's Union Pacific West line tracks.

But transportation experts and advocates previously told Streetsblog that the proposed investment doesn’t make much sense given that the Green Line got a substantial rehab in the mid-1990s. Moreover, they argued the other projects, such as the long-awaited south Red Line extension, should take higher priority.

During the Zoom, Romanelli invited West Side industrial business owners, community activists, and CDOT officials to share their perspectives. The business owners echoed Romanelli's comments, arguing that the current elevated structure was hindering their businesses and posed a safety risk. CDOT planner Joe Alonzo and engineering consultant Jakob Boxberger didn't discuss the idea of raising the elevated structure, but they said the department would look into putting up warning signs. They added that CDOT would need to do a traffic study and design the signs and placement. They agreed to come back for another meeting within four weeks to report on their progress.

Streetblog readers know Romanelli as the activist who helped kill Chicago’s Ashland Avenue bus rapid transit proposal. Now residing in west-suburban Hillside, where he unsuccessfully ran for village trustee earlier this year (garnering less than 9 percent of the vote), he’s currently fighting a state project to improve safety on the Illinois Prairie Path.

In the first few decades of Chicago’s history, industrial businesses tended to cluster around rail corridors to take advantage of the freight rail access, and what is now known as the Union Pacific West line was no exception. The advent of commercial trucking changed the equation some, but the development patterns persisted. Many of the industrial businesses that are still located along the corridor have been there since the 1940s, if not longer.

John Serritella, one of the panelists at Romanelli’s meeting, owns Chicago Anodizing, which has been based in West Garfield Park, at 4112 W. Lake St., since it opened in 1947. As the name suggests, the company applies finishes to aluminum components for clients such as Ford, General Motors ,and Lockheed Martin. Last year, Chicago Anodizing built an expansion on a vacant lot to the west, at 4118-4136 W. Lake St.

The other business owner panelist, Ray Carlson, is a second generation owner of the nearby Chicago Turnrite precision machine parts manufacturer at 4459 W. Lake St.

Serritella said that his company “struggle[s] here on the West Side with truck traffic and getting people to and from [their facility] safely.” While he supported the warning signs, he said that it alone wouldn’t cut it. “Signs is not the only thing. We need infrastructure to [support] people who want to be on the West Side. We want to do something to get businesses coming to the West Side, because we're alone here. Aside from my friend Ray Carlson, there aren't many people left here.”

Notably, Chicago Anodizing has gotten aid from the city recently. Earlier this year, the company obtained the Class 6(b) Cook County property tax classification for the newly expanded property, which is expected to save it $172,494 in property taxes over the next 12 years. The company needed support from the city to get the classification, which the city council gave during its January 27 meeting.

Carlson said that his company couldn’t grow without truck traffic, which has become an ongoing issue for Turnrite. “I got two truck companies saying they won't pick up my product anymore, because it's too dangerous [to maneuver under the ‘L’ tracks],” he said. The issue, Carlson explained, is that trucks with 45-foot trailers simply don’t have enough room to maneuver under the tracks, so he has to pay extra to move the products onto smaller trucks.

Several panelists also complained about speeding and what they described as inadequate lighting along Lake Street. Anthony Waller, owner of Catering Out of the Box at 4300 W. Lake St., said that he personally witnessed and filmed several crashes that happened due to speeding.

Romanelli said that he's interested in the issue because what happens further west on Lake Street affected what happened in Fulton Market District. “I'm sure anyone can say here, no community, no other community in Chicago will tolerate dangerous, antiquated 19th century infrastructure, and neither would the West Side.” However, he didn’t acknowledge until later in the meeting that Fulton Market district has a similar elevated structure, although the support columns are located on the sidewalk. He also never mentions the Loop, which famously has elevated tracks above several of its streets.

With the type of hyperbolic flourish he’s known for, Romanelli said that raising the tracks would “bring hope, prosperity, and bring down crime on the West Side.” He touted the new Morgan/Lake ‘L’ station as a catalyst for development, saying that West Side could see something similar with improved elevated infrastructure. He didn’t mention that recent West Loop development has displaced food warehouses and wholesalers that relied on trucks for their business. For example, he mentioned Google’s Chicago headquarters as a sign of this new prosperity, but didn't acknowledge that it was previously a cold-storage warehouse.

Romanelli did point to one issue that may be responsible for so many trucking accidents. While signs on Cicero Avenue and Pulaski Road, two major thoroughfares, state that that the track clearance is 14 feet, the actual clearance is lower on some segments in between.

CDOT's Alonzo said the new warning signs are an idea worth pursuing. “There's a [sign installation] backlog, but we can prioritize this where we can look at this location or points of concern."

Jacob added that another hurdle would be figuring out exactly what the signs would look like, since it would be different from existing standard city signs. He promised CDOT will try to come up with something “clear and concise.”

As Streetsblog wrote last week, new signs are a reasonable, relatively affordable solution to the problem of truckers getting stuck under the Green Line tracks – as long as Romanelli doesn't get his way by wasting billions in transit funds on a trucking project.