A consultant by day, Richard Day (@richsday) serves on the board of Renaissance Social Services, an affordable housing provider in Chicago (the opinions expressed here are his own.) He lives in Logan Square and is on a mission to find the best hot dog in the city.

More than 300,000 Chicagoland residents have applied for rent relief during the pandemic. The state’s eviction moratorium expired on August 1, and enforcement may start at the end of the month, so tenants across the region are at risk of displacement even as businesses have reopened and the economy starts to rebound.

While the pandemic has brought this crisis to a head, the city has long faced a chronic shortage of affordable housing, including both inexpensive units offered at market rates and subsidized units. As rents rise, neighborhoods become steadily more exclusionary. Streetsblog’s David Zegeye wrote last year:

The population loss in Black communities is connected to the movement of those communities to the margins of the city. Many of my friends say they no longer feel safe walking on their own block and want to raise their children in a safe and accessible neighborhood. However, many of the neighborhoods that have those qualities are unaffordable, so many of my friends have moved further out in the city, or plan to leave Chicago entirely.

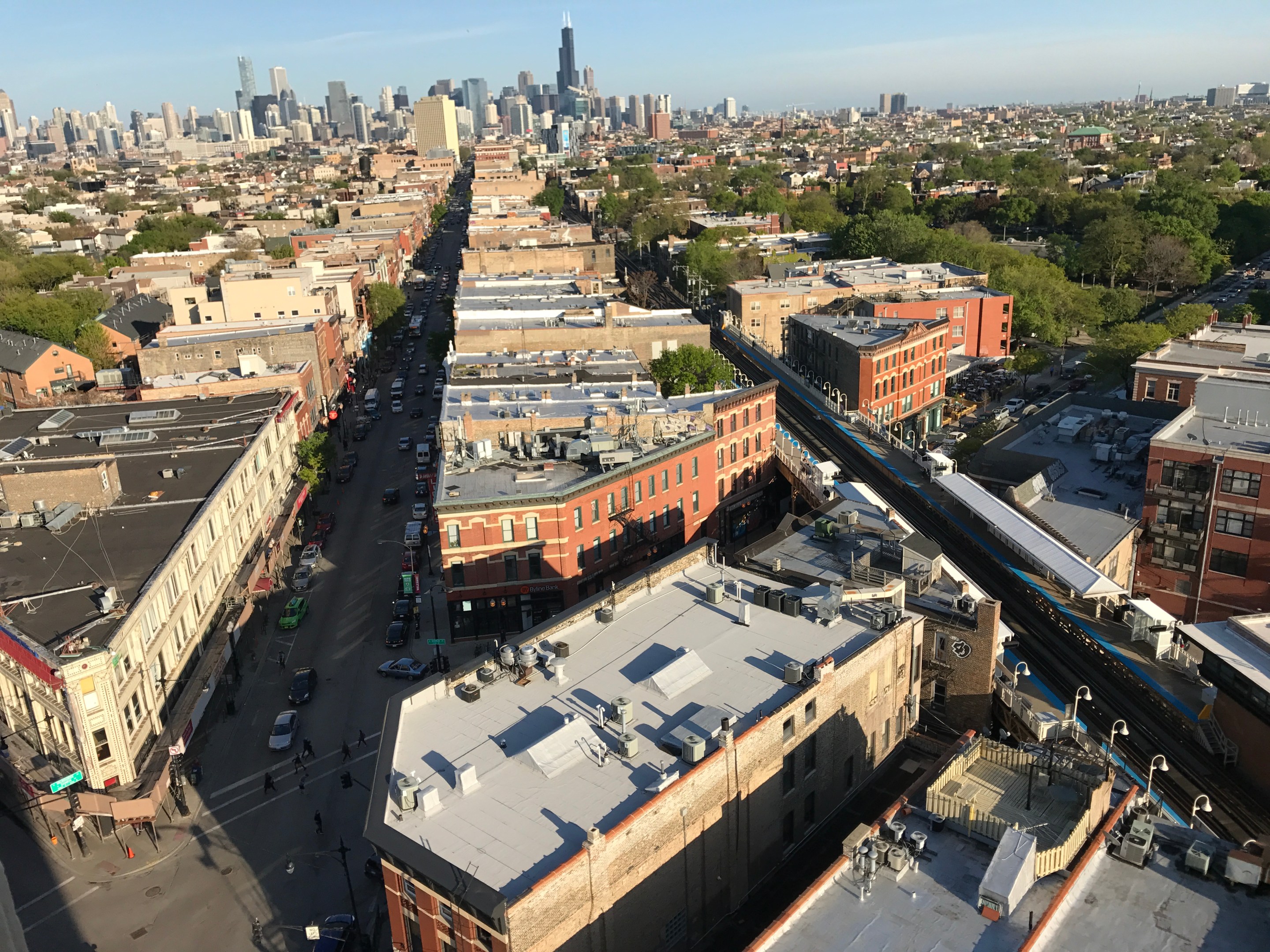

Efforts to address this crisis have often focused on fights over specific developments in gentrifying areas of the city, such as Logan Square where higher rents and property taxes have pushed many Latino residents out of the neighborhood. But even as community leaders, developers, and aldermen wrangle over specific developments the larger trend is unmistakable: lower-income Chicagoans (who are more likely to be Black or Latino) are priced out of the highest-opportunity neighborhoods in the city.

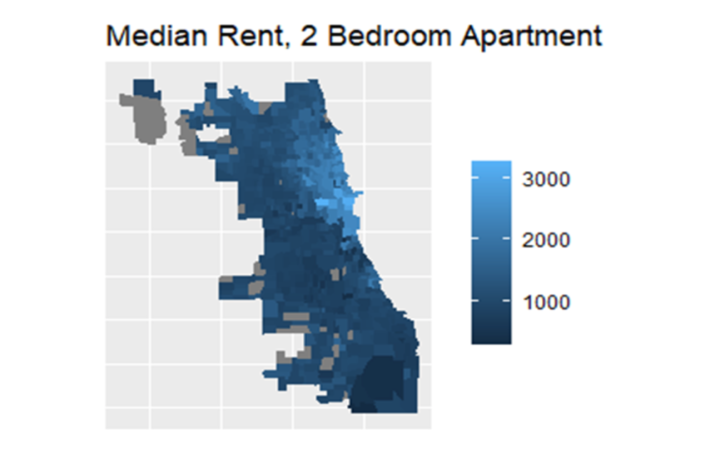

But while media attention often focuses on specific developments, the crisis is actually far more insidious. High rents across the North Side continue to push renters to look for cheaper apartments further west. Here’s what the median monthly rent looked like for a two-bedroom apartment in 2019.

I'd argue that recent upscale developments in Logan Square and Humboldt Park aren’t the cause of rising housing costs in those neighborhoods. Rather, they’re a symptom of higher housing demand in those communities from renters who’ve been priced out of neighborhoods further east. With sky-high rents in communities like Lincoln Park and Lakeview, renters and first-time homebuyers are pushed west. In the process, they’re forced to bid against existing tenants for a limited supply of units and prices rise.

The result? Chicago faces an acute shortage of low-cost housing—and now needs 120,000 new units to make up the gap.

Why is Chicago so unaffordable?

Chicago is relatively affordable place compared to many peer cities. For example, rents for comparable properties are about three times as high in New York City as Chicago. However, housing costs in Chicago neighborhoods that offer public safety and amenities like convenient transit and retail are out of reach for many residents.

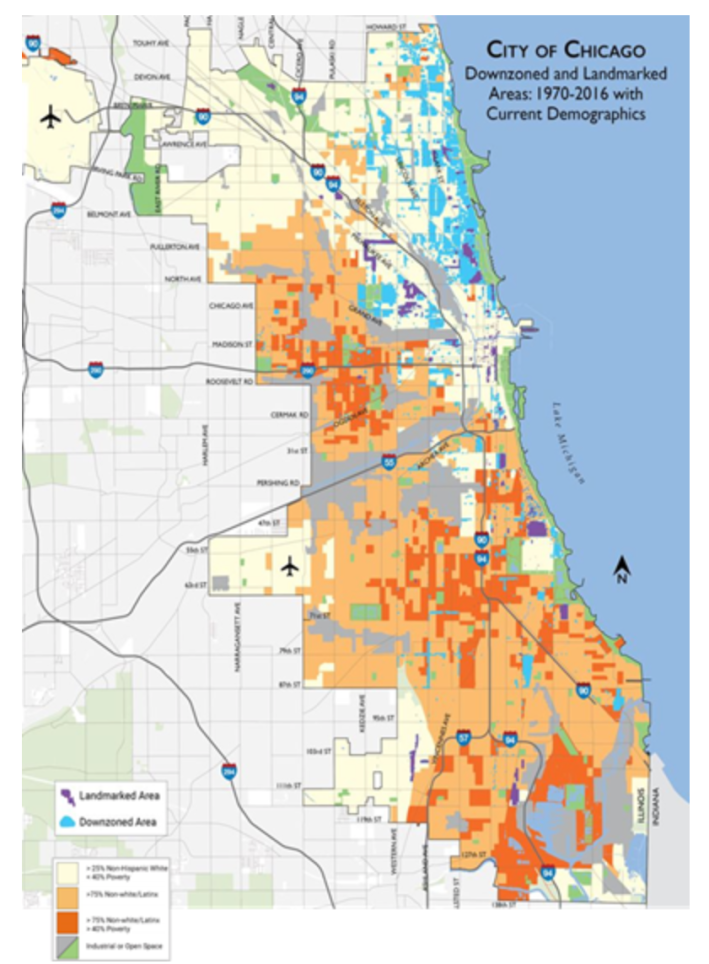

Many of the most desirable, highest-opportunity communities have closed themselves off to new development. On the map below, notice the neighborhoods across the North Side that have been systematically downzoned (in blue), making it illegal to build new courtyard apartment buildings or 2-4 flats.

At the neighborhood level these down-zonings might not feel like a big deal. Construction can be a nuisance; car owners worry about increased traffic and parking hassles from higher-density buildings; and exerting local control over development feels like a standard part of civic participation. But when you add them up, these down-zonings are driving our affordable housing crisis in two ways.

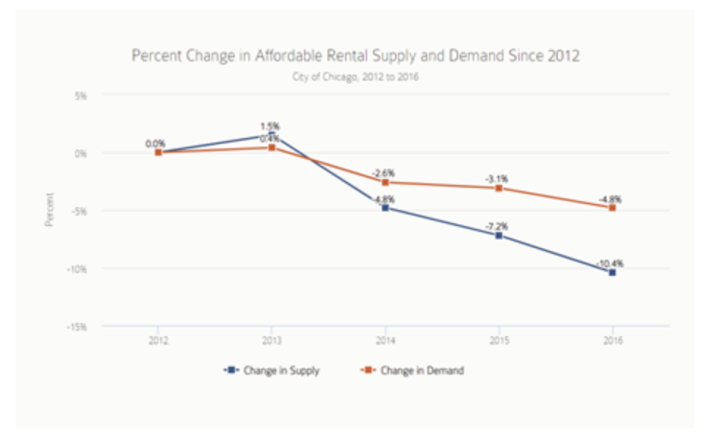

First, downzoning creates housing shortages by reducing the number of homes available. Thanks to aggressive downzoning, along with other efforts to restrict development, the population of Lincoln Park fell from 102,000 in 1950 to 67,000 in 2018. As tens of thousands of Chicagoans were pushed into other parts of the city, they had to bid against other renters for homes, sending prices higher everywhere. This shortage has continued to worsen – between 2012 and 2016 the number of affordable units in the city fell by 10 percent.

And it gets worse. In addition to cutting the amount of housing available, down-zonings also increase housing costs by changing the type of housing available to renters. Single family homes tend to be far more expensive than denser types of housing because they require more land per unit. It’s not a coincidence that Chicago’s most affordable type of housing, 2-4 flats, is disappearing fastest across the north and northwest sides. Not only do our zoning rules cut the supply of units available to renters, but they also make it illegal to build the types of housing that low and middle-income renters could actually afford.

How we got here: a legacy of exclusion

As is true on so many issues in Chicago, our land use decisions reflect a troubled history of exclusion and racism. In 1917, the US Supreme Court struck down explicit, race-based zoning in Buchanan v. Warley. But in 1926, the Court allowed communities to use exclusionary zoning to restrict development based on the characteristics of development, such as restricting development to single family homes, or requiring minimum lot sizes. It was illegal to use zoning to bar non-white residents from living in a neighborhood, but it was perfectly fine to ban the sorts of housing that they could afford to rent.

While communities would continue to use other explicitly race-based efforts to keep neighborhoods segregated, ranging from restrictive covenants to federally supported redlining, they also seized on this new, 'race-neutral' tool to exclude black and brown residents. Between 1916 and 1936, the number of communities with exclusionary zoning rules rose from 8 to 1,246.

Chicago followed a similar pattern. Initial efforts by the Chicago Real Estate Board to define an explicitly race-based zoning code were halted by the Buchanan decision and activism by Black leaders, but white residents fought aggressively to keep the city segregated. In 1923, the city’s first zoning law began to disproportionately limit density in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Over the years, the language changed but the outcomes persisted. In the '60s and '70s communities on the North Side attacked mid-sized apartment buildings as “blighting time bombs,” while fighting for ever-more restrictive zoning codes that shrunk the population of Lincoln Park. In 2016, the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance found that the city’s majority-white wards were twice as likely to be downzoned as other parts of the city.

Of course it wouldn’t be fair to simply ascribe historical motives to contemporary residents. There are lots of reasons why residents are wary of denser development, and these concerns aren’t limited to white neighborhoods on the North Side. Plenty of people may genuinely want to have more integrated neighborhoods, even as they oppose denser development. But we should be honest about what happens when wealthy neighborhoods ban apartment buildings: Those neighborhoods become whiter and more exclusionary.

This history should also make us suspicious of claims that restricting development will help curtail rent hikes. Across the city, the neighborhoods that have made it hardest to build more housing are the very areas with the highest rents. And a review of the academic research shows that building more homes helps keeps housing in the immediate neighborhood more affordable, because it allows renters to move into new buildings rather than simply bid against existing tenants for the same housing stock.

Finally, it’s important to note that not only does exclusionary zoning make Chicago more segregated and unequal, but it also makes the whole city worse off. High rents leave tenants living paycheck-to-paycheck and pull resources out of local communities. High housing prices make it more difficult for new homebuyers to start families. A weaker tax base worsens our pension challenges, and reduces the resources available to invest in underserved neighborhoods. And across the city it becomes harder for people to access the communities, job opportunities, and schools that they need to thrive.

We can do better

Chicago’s housing shortage isn’t an accident or an inevitable consequence of big city life. It’s a choice. If we really want to add more affordable housing we can choose to do so. And if we want to ensure that every Chicagoan has access to neighborhoods with good transit, safe streets, and strong schools, we can choose to do that too. We can start by reversing down-zonings that have rendered much of the city unaffordable and exclusionary.