The future of progressive urbanism in Chicago hinges on how the city manages one specific type of infrastructure: parking. How we store private motor vehicles has and will continue to dictate the shape of the city’s mobility system. Yet Chicago has no dedicated office that plans, studies, or manages parking. Laissez-faire parking management has forced the city’s entire multi-modal transportation system into a state of arrested development. Without rethinking parking, the city is trapping itself into car-dependency. To reverse this, Chicago must start taking parking and curb management more seriously and actually invest the resources required to manage this important infrastructure.

Easy, free or cheap car parking is a "carrot" for car use; it encourages driving. Its mere availability, even at a cost, makes driving possible. Without a place to park, you can’t easily drive yourself to a destination. While perhaps this dynamic doesn’t play out as noticeably in truly car-dependent places, it certainly helps to maintain driving as a choice where alternatives are available in a city like Chicago.

Convenient car parking is also a "stick" that discourages sustainable transportation modes. Parking consumes an obscene amount of space. Whether it is spreading destinations out (like in sprawled suburban communities) or consuming limited street space (as in dense urban neighborhoods), parking greatly restricts any attempts to invest in making alternatives to driving like walking, biking, and transit safe, efficient, and appealing. That in turn cudgels many people into driving whether they really want to or not.

Thus, excess parking quickly becomes a seemingly unbendable force that just reinforces car-dependency. This is especially true in dense urban settings where street space is limited and on-street parking consumes high-demand curb space. How parking is managed, or isn’t – as is the case in Chicago – can radically shape what mobility looks like in a city. However, a well-managed parking ecosystem is about more than just removing parking. It means being strategic about where parking is located, how much it costs, and how well used it is throughout the day.

As Block Club Chicago's Ariel Parrella-Aureli reported last week, the city of Chicago's planning department is working to sell four lightly used city-owned parking lots in Portage Park, North Center, and Lakeview for redevelopment. The sales are expected to bring in more than $10 million for the city coffers. This plan provides an example of what the impact of non-management of city parking assets looks like in practice.

Although these lots are underused, it’s not because there isn’t demand for parking. Rather, between the off-street parking and the curbside spaces, there is excess available parking in these communities. Therefore, in some locations parking should be converted into more productive land uses, but in other locations it must be retained. The question is, does it really make sense to eliminate the parking lots rather than the on-street parking?

This is the type of question that doesn’t get asked, because the city of Chicago doesn't have an office of parking management. However, such questions are incredibly important to ask. If we really want to see the rapid development of bus lanes, or a protected bike lane network, or wider sidewalks, or pedestrian plazas, then we must also understand parking needs and manage parking more intelligently.

Removing metered parking is difficult in Chicago because of our awful 75-year parking contract that requires the city to compensate the concessionaire for any lost revenue from curbside parking removal. But what would happen if, rather than selling off the lots in Portage Park, North Center, and Lakeview, the city kept them and used the off-street parking spaces to compensate the concessionaire for the removal of nearby curbside spaces? There could be some significant positive ramifications.

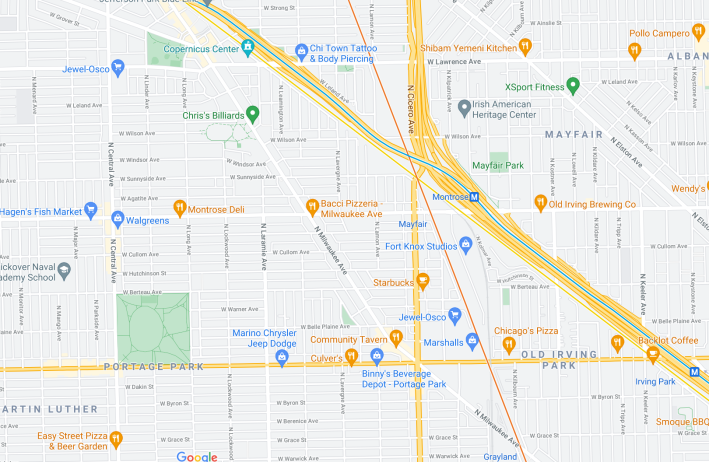

The Portage Park lot, at 4050 N. LaPorte Ave., has 111 parking spots. The three smaller lots in North Center and Lakeview have a total of 126 spaces. If stretched linearly along a street, at about 20 linear feet per curbside space, that equates to nearly a mile of curb that could be freed for uses other than parking cars. Even more curbside parking could be converted into other uses if these lots get redeveloped into housing and commercial space with multi-level public parking garages.

In Portage Park, that would mean all the on-street parking between the Irving Park/Cicero/Milwaukee intersection in the Six Corners area and Lawrence Avenue in Jefferson Park could be converted to more productive uses. In North Center and Lakeview, the number of spaces in the three lots is equivalent to more than enough linear space to remove of all the metered parking on Lincoln between Addison and Wellington.

[In practice, garage parking must be within a reasonable walking distance of one's destination for it to be an acceptable replacement for curbside parking near that destination. -JG]

In both cases, replacing the metered on-street spots with off-street ones wouldn't negatively impact parking capacity, because the lots are currently barely being used at all. Getting rid of the curbside parking would enable the construction of new protected bike lanes, or the full pedestrianization of several blocks of Milwaukee or Lincoln. This raises the question of whether the money the city will earn from the sales is really worth the opportunity costs.

This issue is bigger than those individual land sales though. Without understanding the city’s parking inventory and needs, the city can’t shape better policy to manage parking development in the future. How, for example, could Chicago's transit-oriented development ordinance be improved further, especially in areas more than a half-mile from a rapid transit stop?

What about parking that is little-used at most times, most days of the week and creates empty voids at most times? A parking management office could not only ask these questions, but also start offering material solutions that benefit all stakeholders.

The city must begin exploring ways to better manage its entire inventory of parking and in a way that serves all road users and stakeholders better. In practice this might look like making sure that parking is developed in a coordinated way. Business or institutions that experience parking demand at different times of the day and the week should be encouraged to share lots. Alternatively, private businesses or land owners and community institutions ought to have opportunities to have metered parking installed on their lots in exchange for some of the revenue. Again, this means existing off-street parking is more likely to be used at all times, while enabling the removal of on-street parking occupying valuable curb space.

This doesn’t even get into the potential opportunities that arise if the parking office is empowered to dynamically manage all curb space. As on-demand mobility and at-home delivery increases in popularity, it is vital that a single city office have the power adjust when and how different people and services use curb space. Dense areas require dedicated delivery zones on most blocks. Drop-off areas need to be designated to ensure ride-hail vehicles no longer block mixed-traffic lanes and bike lanes.

None of this can happen unless the city establishes an office of parking management. The impact of parking on all other mobility systems and the value of curb space demands this. The office must be given adequate powers and funded in a meaningful way.

As for a funding source for this new office, I'd recommend reallocating some money from Chicago's bloated police budget. A well-managed mobility system would do far more to positively impact the average resident on a daily basis than the police department does.