After former 44th Ward alderman Bernie Hansen, 76, passed away last Sunday, local politicians and news outlets have, understandably, been highlighting his positive attributes. Hansen served the Lakeview community from 1983 to 2002. Supporters noted his advocacy for LGBT equality, including cosponsoring the Human Rights Ordinance, which expanded protections against housing and work discrimination against lesbians, gay men, and people with disabilities; as well as measures to provide benefits to same-sex partners of city workers. Hansen also selected current 44th Ward alderman Tom Tunney, Chicago's first openly gay City Council member, to replace replace Hansen when he stepped down from the position.

Very sad to announce the passing of former 44th Ward Alderman Bernie Hansen yesterday. Bernie served as Alderman from 1983 until 2003. He oversaw transformational changes in our neighborhood and helped build the thriving community we share today.

— Tom Tunney (@AldTomTunney) July 19, 2021

Notably, in the 1980s Hansen generally aligned himself with the notorious Vrdolyak 29, the bloc of almost exclusively white aldermen who fought Chicago's first Black mayor Harold Washington tooth-and-nail during the racially charged Council Wars. Chicago Reader music critic Leor Galil also noted that Hansen tried to rein in the legendary Lakeview all-ages club Medusa's.

In the mid-80s, Hansen cosponsored a proposal to limit the hours on juice bars, partly due to neighborhood complaints about Medusa’s, one of the most important and influential Chicago nightclubs of the past 40 years https://t.co/QCJcpWsxL1

— Leor Galil (@imLeor) July 20, 2021

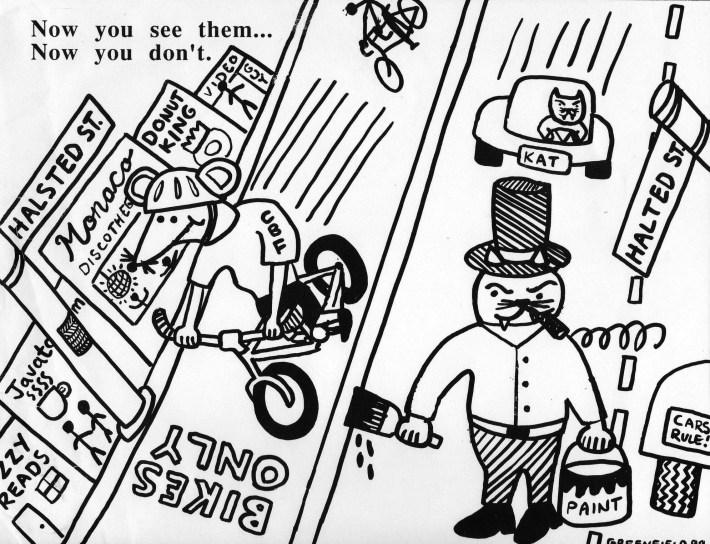

But old-school Chicago bike planners and advocates will remember Hansen as the alderman from one of the the most colorful or, rather, monochromatic episodes in our city's cycling history, the time in 1998 he had the Halsted Street bike lanes painted black.

As detailed in a contemporary article in the Reader by Todd Savage, that November local bike riders were puzzled to see that the bikeways the Chicago Department of Transportation had installed on Halsted in Boystown a month earlier had been covered with black paint.

A nearly-completed streetscape project on Halsted, which included the installation of Boystown's famous rainbow pylons, had widened the sidewalks but narrowed the roadway width to 44 feet. CDOT experimented by installing the bike lanes on Halsted, which was narrower than any other Chicago bikeway street at the time, although the department noted bike lanes had been installed on 44-foot-wide roads in cities like Philadelphia and Portland.

But Hansen claimed he and the community groups hadn't been notified about the bike lane plans, and some motorists found the 10-foot travel lanes, which are fairly commonplace in Chicago nowadays, to be uncomfortably narrow. Some neighbors argued that Halsted, which had plenty of bike traffic even back then, wasn't wide enough to be safely shared by people driving and cycling. Ironically, some of the same folks who didn't want people biking on the street also complained about people riding on the sidewalks of Halsted.

The alderman had city crews paint over the lanes before the streetscape ribbon cutting with then-mayor Richard M. Daley, who ironically had a reputation for bike-friendliness.

"Most people in the city see riding a bicycle as a brave thing to do," Randy Neufeld, then-executive director of the Chicagoland Bicycle Federation, now the Active Transportation Alliance, told Savage at the time. "I can't think of a more important, more critical [area] where you could put lanes than on this section. You have a high use of bicyclists, a very busy commercial area. If it's going to work anywhere, this is where it's going to work."

Bike advocates who met each other via the recently-launched Chicago Critical Mass bike parade like Todd Sperling and T.C. O'Rourke canvassed the neighborhood to win support for bringing back the bike lanes. "There are a few people who think that the street is too congested or too narrow, and the professional traffic engineers at CDOT disagree," O'Rourke told Savage. "That's a key point: letting people who don't really know, who aren't professionals, decide what is safe and what is not safe."

Savage wrote that when he contacted Hansen about the bike lanes, the alderman initially hung up on him, and later sounded irritated about having to discuss the issue again. "Mr. Whatever His Name, Mr. Bicycle Man [then-CDOT bike coordinator Ben Gomberg] decides he's going to organize some of the bicycle riders and start aggravating me," Hansen told the Reader. "He did, and I don't have enough time to get aggravated with his nonsense."

After the advocates presented Hansen with hundreds of petition signatures in favor of reinstating the Halsted bike lanes, the alderman eventually relented. One positive byproduct of the bike lane battle was that it was a gateway for advocates like O'Rourke and fellow campaigner Mark Counselman to take jobs as bikeway planners at CDOT. “I wrote so many damn letters that Ben Gomberg essentially said, let’s just put this kid on the payroll,” Counselman later told me.

In fairness, Hansen eventually came around to being somewhat more bike-friendly, and a couple years after the lanes were reinstalled, when I was working at CDOT getting bike parking racks installed, he attended a ceremony for the installation of Chicagos 10,000 rack outside a tavern in his ward.

But despite his redeeming qualities, I'll always remember Hansen as Chicago's second-least-bike-friendly alderman named Bernard.