Update 7/20/21, 4 PM: Landmark Development provided the following statement. "There has been no partnership formed between the Bears organization and Landmark regarding ONE Central. Landmark has simply kept the Bears and other community stakeholder groups informed of key activities related to the development of ONE Central." This appears to contradict what Sean Huang stated during the presentation.

A meeting on One Central from last month shed light on a range of topics – from plans on the U.S. Steel site, to an agreement with the Chicago Bears, as well as state financing – but left attendees with more questions than answers.

The meeting was hosted by RSO Architecture, which is helping Landmark Development, the Wisconsin-based firm behind One Central, with the project. RSO reps said the firm believes in Landmark’s vision that One Central will serve as a nexus for Chicago. Although recordings of other meetings have been uploaded to RSO's YouTube channel, there’s still no publicly available recording, which I was hoping to include in this article.

Elizabeth Breitlow of Landmark was supposed to lead the presentation, but she and several colleagues had been busy throughout the week presenting their proposal to city departments before applying for zoning entitlements. Sean Huang of RSO took over the presentation and encouraged an active Q & A session.

Huang opened the presentation by claiming that the One Central transportation hub is now fully financed by the private sector, both from local and international investors, who he said have recognized the site as an exemplary model for transit-oriented development in Chicago. He said this initial phase will be known as the “civic build” and will hire 19,000 workers to complete the hub in about four years.

But if the transit hub is fully financed, why is One Central pursuing a public-private partnership (P3) with the Illinois legislature, in which the state would pay $6.5 billion over 20 years for the transit hub? If the transit hub is an attractive target for private investment, why bother pursuing state funding? I decided to save this question for the Q & A portion.

In May, State representative Kam Buckner moved to block the state financing for One Central, in response to what he characterizes as “underhanded” efforts in Springfield to get the subsidy approved.

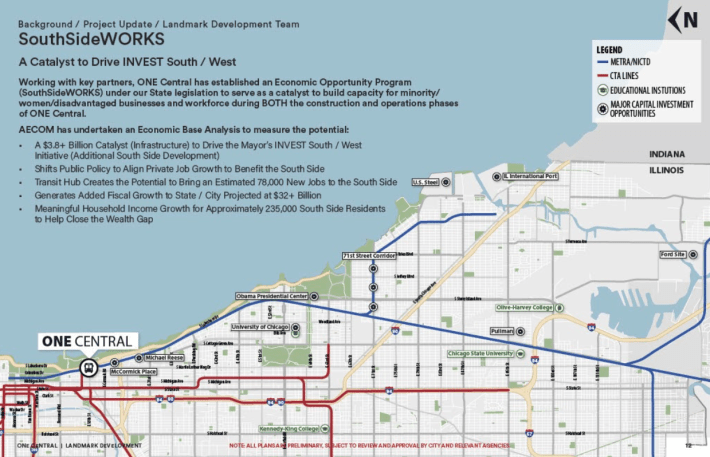

As discussed in previous meetings, the purported goal of the One Central is to link the Metra Electric District line, the South Shore Line, Amtrak, a new branch of the ‘L’, and a proposed autonomous vehicle network called the “CHI-Line” into a single hub. According to a transit study Landmark completed, they expect around 100,000 people passing through the station every day. They say the expected demand would significantly boost ridership across Chicago’s transit network, while expanding capacity across downtown, and providing a revenue stream for Illinois.

To justifying the location of the transit hub, Huang noted that the site was originally the location of the Illinois Central Station, which was one of the busiest rail stations in the world by daily boardings. The proposal has received support from a range of civic and community groups, such as the Chicago Chamber of Commerce, The Executives' Club of Chicago, and the Carpenter’s Union.

However, transportation advocacy organizations like the Active Transportation Alliance and the Metropolitan Planning Council are not endorsing the plan. ATA spokesperson Kyle Whitehead stated bluntly in a blog post, "The proposed One Central tower and transit hub on Chicago’s South Side is poorly conceived and wouldn’t increase transit access for the city’s highest need residents."

As a part of the P3 agreement, Landmark says it's creating an economic opportunity program known as SouthSideWorks to expand job and housing access to South Siders. With private financing, Landmark promises to develop workforce housing on vacant land along South Side transit lines, such as Metra Electric and the Green Line. One piece of land they’ve been eyeing is the old U.S. Steel site in South Chicago, where they say they are exploring options to bring back manufacturing jobs to portions of the land.

The planners say the transit hub would contain several million square feet of retail, which would be divided into four distinct districts. The northern portion, which will hold most of the development’s residential units, will be designed after a typical neighborhood retail corridor for small businesses. The area around the transit hub will be known as an “experiential district,” a reference to the notion that patrons will “experience” the Chicago "brand." This will include a welcome center to the city, Chicago-specific stores, as well as retail catering to transit riders

Since Soldier Field does not host retail establishments, One Central is partnering with the Bears to allow them to run several restaurants and memorabilia and gift shop for attendees and tourists. If Landmark Development is this far along in a partnership with the Bears, that calls into question the Bears’ supposed interest in relocating from Soldier Field to Arlington Heights.

Next to the transit hub would be a “lifestyle district”, which the planners say would be experimental by design. Huang said many big-name brands have recognized that large retail establishments are no longer the appropriate format to attract in-person customers. To cater towards changing consumer behaviors, the district’s retail stores would be there to primarily show off a brand’s catalogue and new merchandise. Customers would have the opportunity to browse and try out new goods but would purchase the items online. The belief is that allowing customers to experience their goods will give big-name brands a competitive edge over typical big-box retail formats.

Landmark said it recognized convention attendees have few businesses immediately surrounding McCormick Place that they can easily access. To fix this, the southern portion of One Central would become an entertainment district, which will directly connect to McCormick Place. The entertainment district would host nightclubs, comedy clubs, movies, and visual performances. For small establishments to thrive and create a vibrant cultural scene, certain venues would be reserved for them at affordable rents. Landmark expects an active nightlife scene and hopes to draw residents from across the city.

The commercial and housing portion of One Central will be known as the “private build” and is envisioned to be built over a 15-year timeframe. Towers would be in the 800-to-1,000-foot range to maximize site’s density and lower the cost of construction. After the developer hosted several conversations with residents in nearby high-rises, the designs of the towers have been reconfigured to be less imposing and preserve neighbors' views of the lakefront.

The Q & A portion is where more curious details about the development emerged. To get a sense of how RSO would respond to questions, I first asked if a route had been decided for the new ‘L’ branch, since planners have previously brought up concerns that the Loop will be overburdened. The planners said the branch will follow the St. Charles Air Line towards the Alley ‘L’, and the CTA will ultimately decide the final route.

I got bolder and then asked why Landmark is pursuing a P3 agreement with the state government, when the civic build is supposedly fully financed, and the money could be better spent on South Side transit projects. Huang responded that the partnership is not just a contract but is a part of state law and a finalized deal. As such, he said, neither party can back out of the deal and are legally required to follow through with the terms of agreement. This means that a bill, such as the one Kam Buckner introduced, is the only way to end the agreement.

Huang pitched the civic build as a revenue stream that will fill the state’s debt obligations and provide a long-term source of income. With regards to whether the funds should instead be spent on other transit projects, he said we shouldn’t view the issue through an either/or binary. He said he doesn’t see why both goals couldn’t be pursued. This point seemed half-hearted given that Illinois is constrained in its spending priorities, especially since Huang acknowledged Illinois’ debt in an earlier point.

One attendee expressed concern that One Central will continue segregating lakefront access, and another was worried that there hasn’t been enough community engagement. Huang responded by arguing that there's currently little infrastructure connecting the South Loop to the lakefront and that the development will provide pedestrian-only access to the lake, so that east-west car traffic doesn’t disrupt neighbors. He also reiterated that Landmark has attended and hosted several small community meetings to address resident’s concerns, and lead developer Robert Dunn has personally answered most of their questions sent over email.

Huang added that One Central will pilot new security strategies, which he didn't discuss in more detail, and advances in green infrastructure that will help the neighborhood’s storm drainage and net-zero goals. He said the developer is looking into the possibility of extending CHI-Line beyond its initial route to include other nearby developments, such as The 78 and the Bronzeville Lakefront, to better integrate them into Chicago’s transit network. One Central hopes to replicate the success of Streeterville by being a gateway to the South Side, and Huang said Landmark is confident the site will be dense enough to support all the retail and commercial uses.

One Central certainly fits Daniel Burnham’s “Make no little plans” ethos, but as yet it hasn’t stirred the public’s blood, largely because important questions are still unanswered. Rather than justify why they need state support if the project is already financially feasible, Huang deflected the question by saying how great One Central will be for Chicago. Given the city’s history of using public funds for private developments, One Central has not provided the confidence that Illinois has made a good deal with our money.