Fifty years ago, Charlie Roche, an Irish immigrant who loved growing roses and working with his hands, got a flier on his front porch warning him that his house might be destroyed to build a freeway.

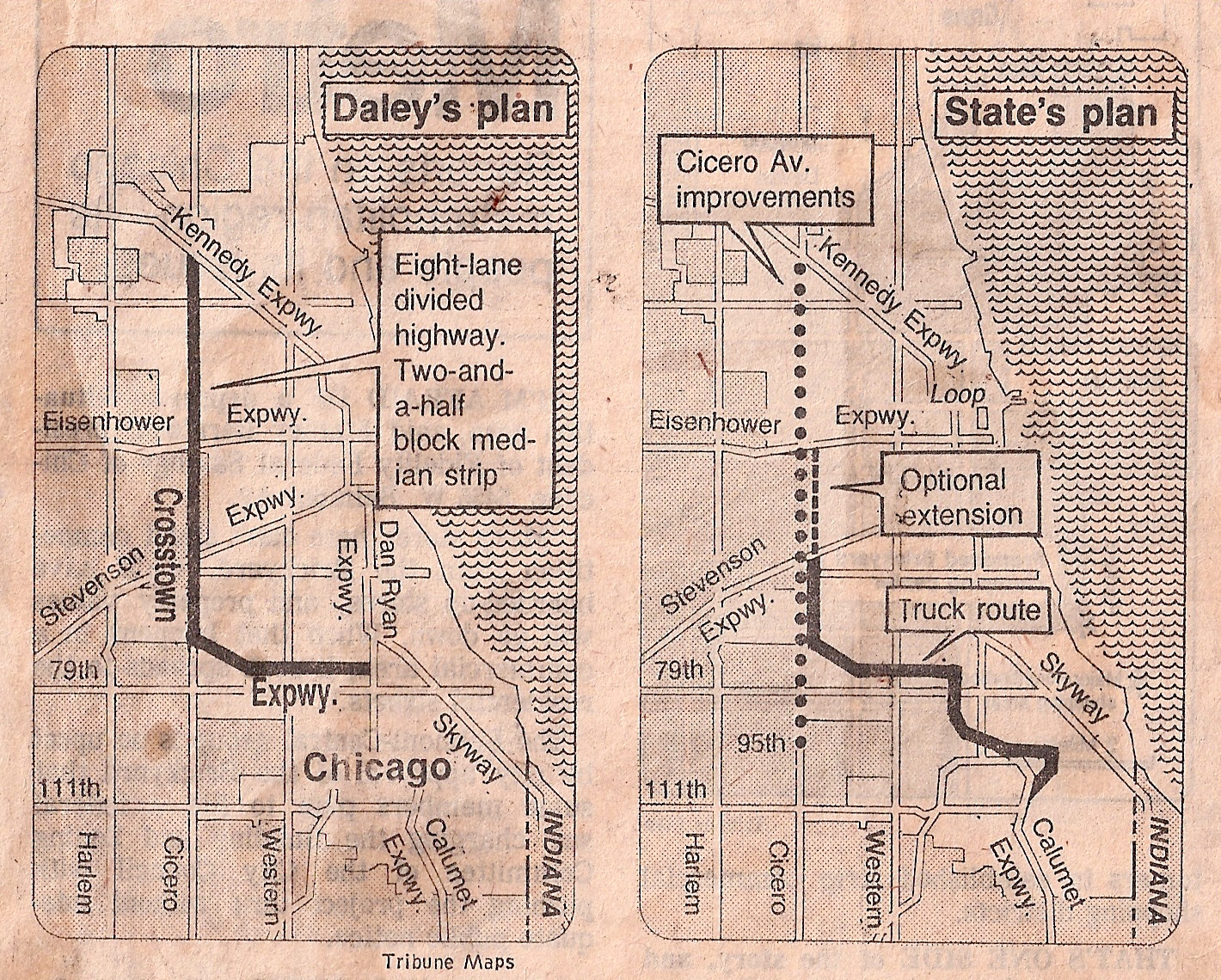

The flier said that his two-story home on a graceful, tree-lined Irving Park block, which he had just bought two years ago and was fixing up, could be in the path of an eight-lane, 22-mile highway that would run east of Cicero Avenue from the Kennedy Expressway south to 75th Street.

“It was a disaster about to happen to him, after all his work,” said Marian Roche, Charlie’s widow, who still lives in the same house.

Charlie Roche went to an organizational meeting at a local Catholic church, and became a leader in one of Chicago’s most unusual protest movements – the fight to stop the Crosstown Expressway. A group of middle and working-class white, Black and Hispanic families, rallied by Protestant ministers, Catholic priests, and Saul Alinsky-trained organizers, fought a big dream of the late Mayor Richard J. Daley, and ultimately won.

The Crosstown battle is unknown to most Chicagoans under the age of 60 – but is vividly remembered by seniors in the neighborhoods the highway threatened – from Irving Park to Humboldt Park, and from Little Village to Garfield Ridge. It showed that ordinary people, working together, can help stop destructive projects and bring about positive change – funds for the Crosstown instead went to other road work and the CTA.

The fight to stop the Crosstown, around with other anti-freeway revolts across the country, also helped mark the end of the inner-urban highway construction that had destroyed neighborhoods and divided cities around the country during the 1950s and 1960s.

“It was a major national turning point,” said Bob Creamer, partner and founder of Democracy Partners, who worked on the “Citizens Action Program” to stop the Crosstown. “Everyone thought the Interstate highway system was a way to solve every problem, but it was the cause of so many problems – suburbanization and dividing people in the inner cities.”

“There was definitely community outrage,” said transportation consultant Steve Schlickman. “They had the hindsight of all the other communities affected by the Interstates.”

A crosstown, north-south route was in highway plans for Chicago from 1939 on, according to transportation historian Andrew Plummer. In the early 1960s, the Chicago Automobile Club, the local affiliate of the American Automobile Association or AAA, began to advocate for the construction of an expressway running north and south, and the Chicago Plan Commission announced endorsement of the proposal in the summer of 1966.

Governor Richard Ogilvie announced the release of state funds for the Crosstown in late 1971, said Plummer. A transit line was supposed to be part of it.

Promoters talked up how the expressway would relieve congestion, help business and create jobs. But it threatened to displace 10,000 to 30,000 residents, and hundreds of businesses. Marian Roche recalled that one of the sore points is that officials wouldn’t explain exactly where the road was supposed to go.

A big problem with the design of the proposed project is that it included a four-block gap in the middle, between the north-bound and south-bound sections, said Luann Hamilton, a retired Chicago Department of Transportation deputy commissioner.

“Who’d want to live there, even for better transit?” Hamilton asked. “You create this huge area that’s a no man’s land.”

A lot of initial interest in stopping the expressway came from organizations affiliated with Catholic parishes along the route, who did not want their congregations carved up by the highway, said Creamer, who is married to Illinois Congresswoman Jan Schakowky. Pastors were ready to engage with the Anti-Crosstown Coalition, part of CAP, “because their parishioners were up in arms,” Creamer said.

CAP planned and conducted demonstrations about every week. “We’d invite the TV cameras and they’d show up,” said Creamer, who noted wistfully that there were more newspapers in those days. The actions included both big rallies and smaller demonstrations in which ordinary citizens would walk up to government officials to ask questions.

Neighbors would call neighbors to turn out crowds for actions, and support got bigger, Roche said.

“A neighbor used to tell me, ‘You can’t fight City Hall,’ and then she became active,” Marian Roche remembered.

One of the demonstrations in 1972 involved an Irving Park resident’s pet duck – protesters claimed that Milton Pikarsky, the head of the organization designated by the city to oversee the expressway’s planning and construction, was “ducking” questions. The duck was all over the news – both vaudevillians and political activists know that nothing beats kids and animals for getting attention.

Plummer said the vigorous local opposition reflected the growing “anti-highway sentiment” across the country, fueled in part by demonstrations across the country to protest the Vietnam War and support Black civil rights. Citizen opposition also stopped other urban expressway projects in the 1970s, including in Seattle, Los Angeles and New York City.

The coalition benefitted from organization, energy, and luck, because the Crosstown had become a campaign issue in the gubernatorial battle between Ogilvie, a Republican, and Crosstown opponent and Democrat Dan Walker. Roche remembers going out in miserable weather on Election Day in 1972 with voter education handbills listing every candidate’s position on the Crosstown.

Walker won, but the Crosstown wasn’t quite dead yet. Mayor Richard J. Daley kept pushing for it, though he considered giving up the northern leg. After Daley’s death, his successor, Mayor Michael Bilandic, did not have “the same allegiance” to the project, said Plummer. Also, the costs kept growing, making it a harder sell.

When Jane Byrne took over the mayor’s office in 1979, she and Governor Jim Thompson finally killed the Crosstown, and the approximately $2 billion in federal funds earmarked for both the highway and a proposed Franklin Street Subway were reallocated to transit agencies and road projects. The transfer was made possible by a federal law that allowed federal money allocated for Interstate highway construction to go instead to almost any highway or transit project.

The “Interstate transfer funds” supported the extension of the Blue Line to O’Hare International Airport and the construction of the Orange Line to Midway Airport, according to Schlickman who was at the CTA at the time.

“The deal was fantastic,” Schlickman said. He noted that Byrne got criticized because half the money went to other Illinois road projects outside of Chicago. But the money made significant improvements to the CTA system, and Byrne couldn’t have done it without the governor’s help, Schlickman said.

In the first decade of this century, Mayor Richard M. Daley floated a vision of a truck-only Crosstown along a railroad right-of-way, but it didn’t materialize.

Creamer said that the Crosstown history teaches that ordinary people can successfully fight for less destructive, less-polluting transportation projects.

“Transportation infrastructure in the United States is well behind that of other countries in many ways,” Creamer said. “A lot of that has been driven by the fossil fuel industry. If ordinary people organize, they can make a lot of difference.”