Active and sustainable transportation is often assumed to exclusively be the bailiwick of urban life. The importance of transit service and walking and biking infrastructure to the suburbs—connecting residents to jobs and cultural activities in the city, as well as providing healthy and safe recreation in their own backyards—can get short shrift. The Active Transportation Alliance put a spotlight on communities outside the Chicago city limits last week with Suburban Action Week, an impressive lineup of twenty-five virtual workshops, advocacy talks, and county updates covering transportation issues relevant to the six million Chicagoland residents living outside the city.

Saturday’s programs included a training and action plan worksheet on advocacy basics; a workshop on strategies for inclusive community engagement; and “Ask an Engineer: How Projects Get Built,” an illuminating look at the process, players and timelines involved in creating bike and pedestrian infrastructure improvements.

Michael Kerr of Christopher B. Burke Engineering, a large local firm that serves provides engineering services for 27 municipalities, led the “Ask an Engineer” session. Kerr walked through the steps of road improvement projects that fall under local jurisdiction, from concept to construction—a four-step process that can take anywhere from three to five years or more. Pre-Phase I is initial planning: identifying the location, funding sources and lead agency on a project. Phase I is the evaluation of environmental impacts, coordinating public involvement, and obtaining design approval from the appropriate agencies: the most critical part of the process according to Kerr. Phase II is the development of design specifications, budget, timeline and bidding—a process Kerr said could take up to a year alone. The final phase, the one most visible to the public, is construction and closeout.

Kerr noted that projects on major roadways that are overseen by the Illinois Department of Transportation might be subject to more strict design criteria and more extensive agency reviews than ones that aren't. On the bright side, Kerr said IDOT recently updated bicycle and pedestrian policies, adding accommodations for bikeways and pedestrian infrastructure and making it easier to include these improvements to future road projects.

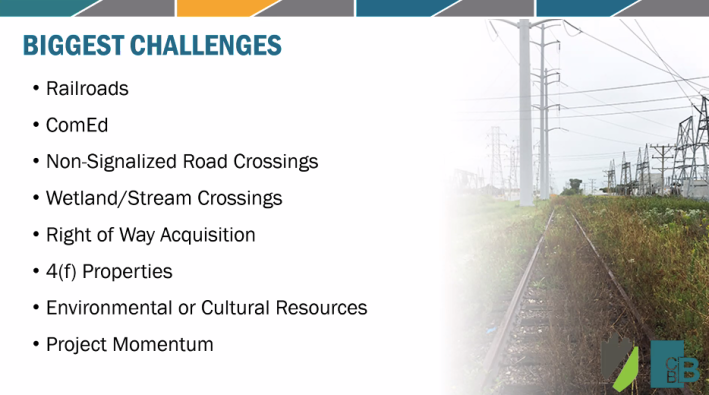

Kerr walked through the biggest challenges that come up during the multi-phase, multi-year process of improving bike and pedestrian accommodations on roadways. Topping the not-short list was railroads, which Kerr said are “not progressive” and are unlikely to go beyond baseline requirements; and ComED, “a good partner,” according to Kerr, but that “their process takes a long time.”

Another big speed bump is obtaining necessary right-of-way acquisitions, which Kerr said can take up to 18 months. Other unforeseen delays like environmental or cultural clearances—for instance cultural artifacts uncovered during construction—can crop up well into a project.

All these challenges feed into the last item in Kerr’s list: Momentum. “This is where advocacy helps,” he said. “Our biggest interaction with the public is in Phase I. Then we get design approval and then we go away for two years. It’s almost unfathomable to the public that we’re still working on this thing. A lot of these projects last through multiple administrations. If advocacy groups can step up it really helps the project momentum.”

In a lively Q & A, Kerr fielded questions that ranged from general inquiries about the cost of road modifications to specific concerns of session attendees. One attendee asked how much more expensive it is to modify plans to accommodate bikes and pedestrians. Kerr said that road projects have often been in the works for years before the public hears about them, and making revisions for bikes and pedestrians is cumbersome at a late stage. Kerr recommended developing complete streets plans in advance, so that compelling arguments for bike and pedestrian improvements are on hand when IDOT is ready to update a road.

Another attendee asked if initial contact with engineering firms needed to come from municipalities or if local bike clubs could make the first call. Kerr encouraged advocates and bike clubs to reach out to engineering firms. He said bike clubs could have a big impact on project design, giving the example of the new two-way protected bike lane on Sheridan Road in Evanston, running along the Northwestern University campus. “I had recommended a one-way bike lane on each side of the road,” he said, “but the local bike club and student advocates said there was no way students should have to cross Sheridan. They wanted two lanes on the same side of the road, which was the right call. They changed the decision on how it was built.”

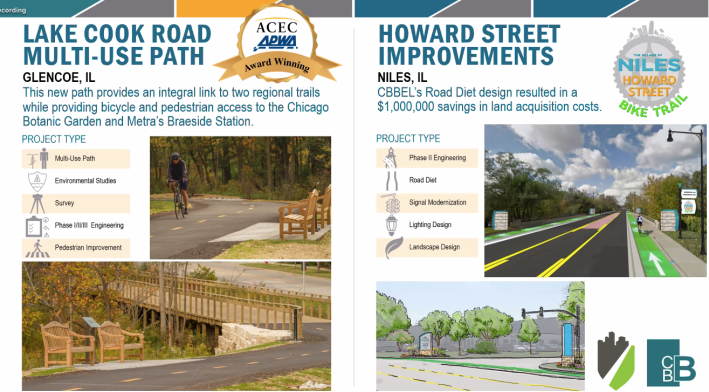

Kerr finished his presentation with about a dozen examples of projects led by Burke Engineering, including the Northwestern bikeway, the Lake Cook Road multi-use path in Glencoe, a pedestrian bridge replacement in Palatine, and the addition of bike lanes on Howard Street in Niles—a “road diet” that reduced a four lane road, with two lanes in each direction, to a three lane road with a center turning lane. The 12 to 14 feet freed up from the fourth lane is allocated to bike lanes on each side of the road.

Road diet treatments have benefits beyond creating safe paths for bikers. “You add a turning lane, reducing left turn [crashes] and make street crossing easier for pedestrians,” Kerr said. “Road diets make the road safer for all users. The tradeoff is there may be some delay [for motorists].” Of course, there's often a political backlash from drivers if they feel their commutes aren't convenient enough, which can make or break road diet proposal, so Kerr said traffic studies are necessary for these kind of projects.

Kerr encouraged advocates and bike clubs to contact him with questions, or to request assistance with an idea, at mkerr[at]cbbel.com.