Transit oriented development stands as perhaps the most significant development trend in Chicago in recent years. Aiming to concentrate parking-lite, dense housing near public transit stations, proponents argue TOD best utilizes existing infrastructure and allows for sustainable growth. Despite one of the country’s most extensive rail transit systems, Chicago was a late adopter of modern TOD policies, passing its first ordinance in 2013.

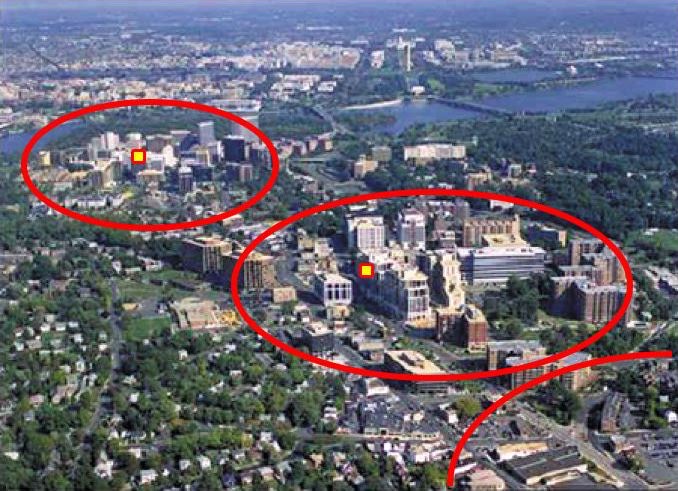

Arlington County, Virginia, is often cited as a national leader in TOD with dense development concentrated around metro stations.

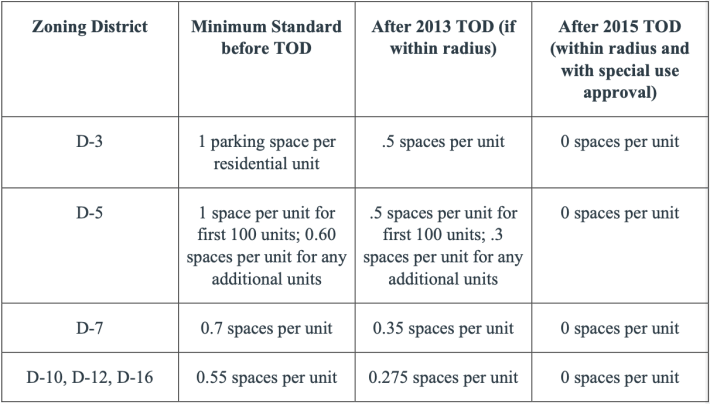

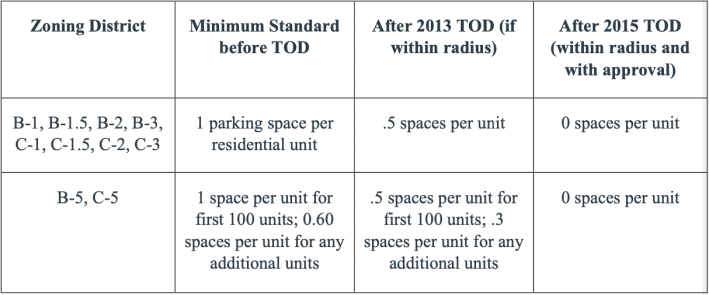

That first TOD ordinance let developers build 50 percent fewer parking spots than the usual 1:1 parking ratio requirements for many new residential developments within 600 feet of a CTA or Metra station, or 1,200 feet on designated Pedestrian Streets. In 2015, the city expanded the ordinance, allowing parking reductions for developments within 1,320 feet (a quarter-mile) of transit and 2,640 feet (a half-mile) on P-Streets. The 2015 TOD ordinance also completely waived the car parking minimums if developers receive special use approval.

I used the deregulation of minimum parking requirements created by these two TOD ordinances to assess how parking minimums impact the supply of parking in residential development. Others have tried to assess parking minimums by considering what happens when developers build the minimum amount required.

However, if developers choose to build only as little parking as allowed, then this suggests parking minimums may be holding them back from building less parking than that, or none, in cases where on-site car parking isn't needed, and may drive up the cost of housing units. I looked at how much parking developers opt to build after they were deregulated. I found that parking minimums have, in fact, been forcing developers to build more parking than they otherwise would.

First, I downloaded building permits dating from January 1, 2009 to March 25, 2018. Out of these, I created a “control” group of developments on parcels that would now be eligible for TOD parking reductions, but were built before the TOD ordinances made that possible.

For example, an apartment complex built next to a CTA station in 2010 would go into my “control” group, as would a development built in 2014 but 610-feet from transit. If built today, these locations would qualify for TOD parking reductions. Then I created two separate “treatment” groups: one for developments that could benefit from the 2013 ordinance when built, and the other for developments that could take advantage of the 2015 ordinances when built.

Next, I tried to gather data on the number of parking units offered on-site and the number of residential units at each development. The city’s permit often had information on residential units, but seldom for parking units. I used a variety of methods to get that info. If it was a planned development, the building plans were generally available. That was also the case if there was an associated rezoning. Other times I found the parking info in building marketing materials. For smaller developments, a few times I went to Google Maps and simply counted. In the end, I was able to find the number of residential units and parking spaces for 222 of 241 relevant developments, or about 92 percent.

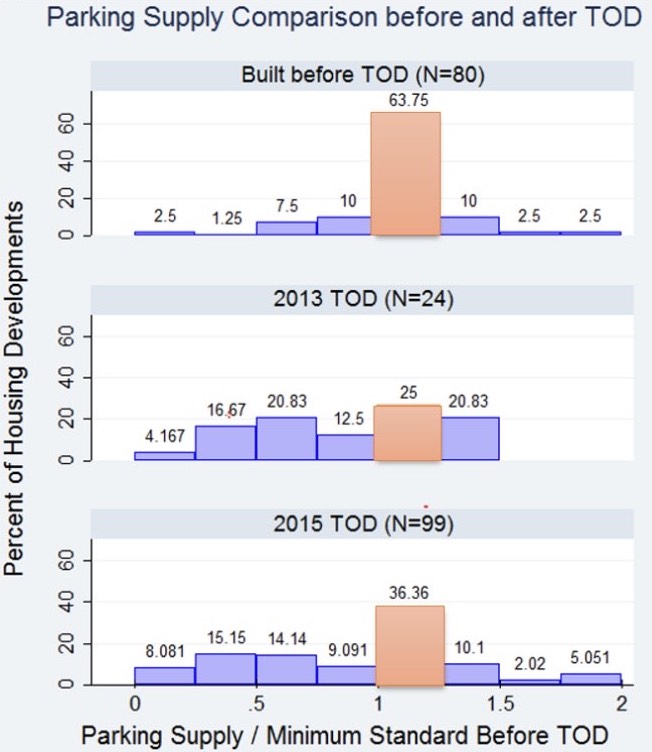

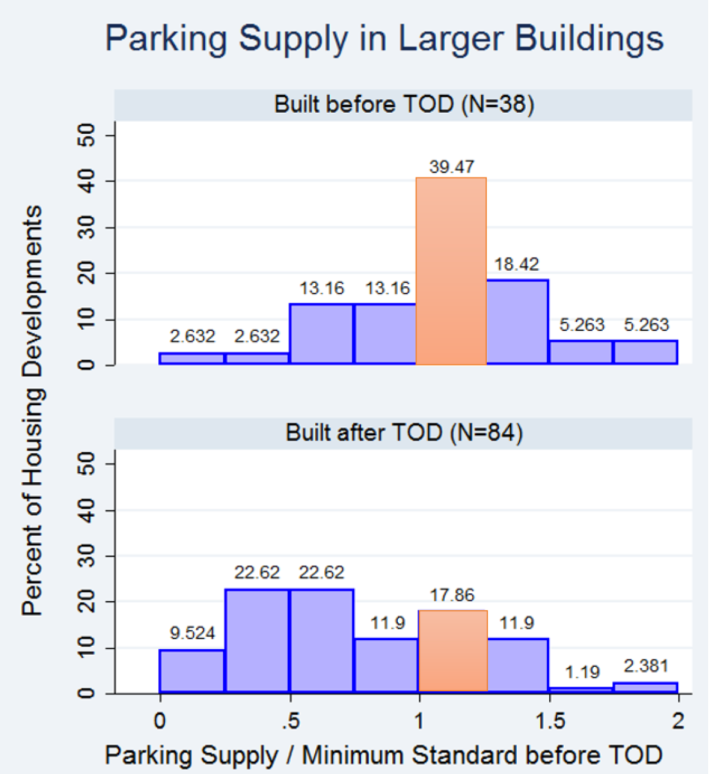

My analysis then looked at the ratio of parking spaces to residential units. I compared the spots-to-units rate that was actually built to what the zoning required to be built before the TOD ordinances were passed. In the pre-TOD developments, there were instances where developers were granted variances to reduce their parking. But, generally speaking, developers had to build as the code demanded, with 63.75 percent of projects building exactly as much parking as needed or just 1.25 times it.

Chicago urbanists generally applauded new TODs in the city’s neighborhoods. (However, many have since come to believe that there were an insufficient number of affordable units included in many of these these projects to mitigate the impact of new upscale condos and apartments on neighborhood property values, property taxes, and rents.)

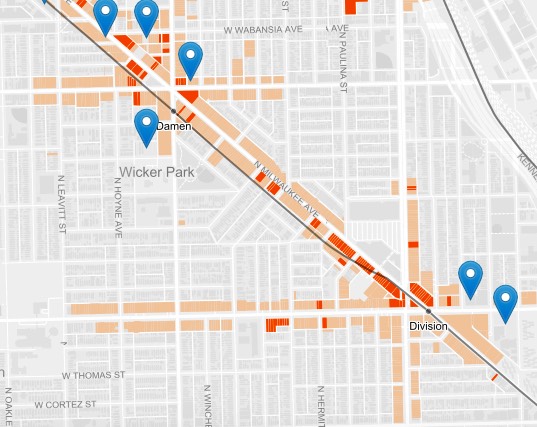

Milwaukee Avenue, for example, has seen a host of new developments along the Blue Line. Building off that, my analysis considered in which zoning districts developers were most likely to deviate from the old parking minimums (i.e., downtown versus neighborhood business/commercial districts.)

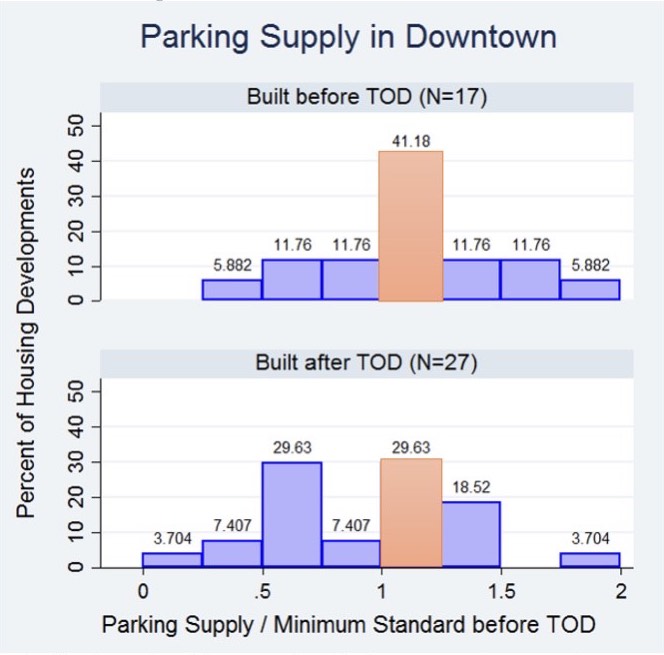

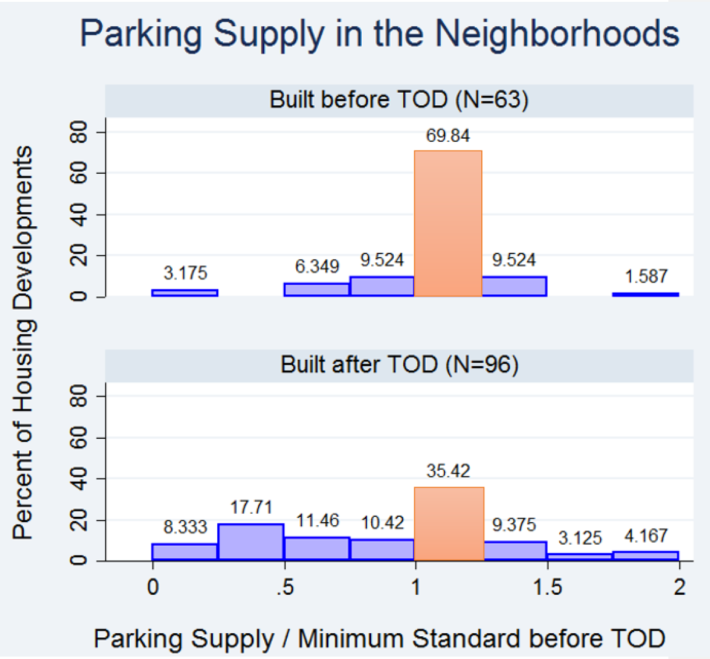

I found that developers in the neighborhoods were more likely to build below the old parking requirements than in downtown. That comes as little surprise given that downtown already had more relaxed parking requirements prior to the TOD ordinances. In addition, many downtown projects are built as planned developments, which gave them some leeway from the zoning code mandates pre-TOD.

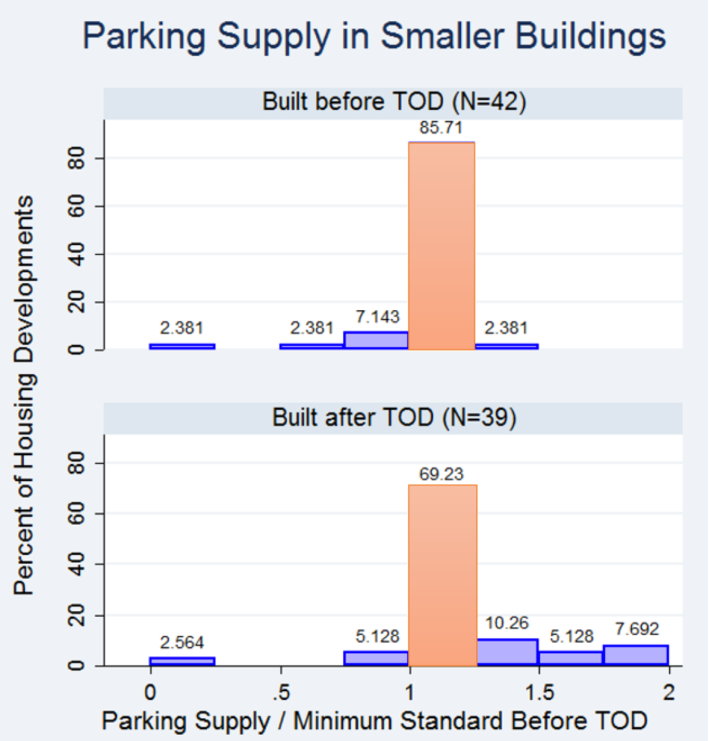

Finally, I considered in what types of projects developers were most likely to deviate from the prior parking requirements. I found that developers took advantage of the TOD ordinance most often for larger projects with nine or more units. Since larger developments are more likely to require built-in garages (with underground garages being the most expensive form of on-site parking), parking is a greater cost in bigger developments. A developer building a 3-unit walk up can likely fit parking for each resident in a backyard garage, while a developer for, say, a 100-unit building would need to build some structured parking to offer a significant number of residents a spot.

These first two TOD ordinances have shown that developers believe there is a market for dense, parking-lite housing near transit. The city expanded its TOD policy in January 2019 to include a handful of CTA bus corridors as well, so TODs will certainly continue to play a major role in Chicago’s future urban development. Unfortunately, so far much of the TOD has concentrated in wealthier and gentrifying parts of town. Aiming to tackle that geographic disparity, Chicago released its first-ever equitable TOD plan in September 2020. Perhaps, in time, developers will find that demand for TOD holds across the city.

I am happy to send a copy of the thesis this article was based on to anyone who is interested. Please email me at bornakhoshand[at]gmail.com to request one.