My interest was piqued when I came across a San Jose Spotlight article in Streetsblog USA's daily headline stack announcing that San Jose, California is looking to add more mileage to its current 400 miles of on-street bike lanes. I was surprised to know that San Jose, the largest city in the San Francisco Bay Area, with a population about a third the size of Chicago's, has that much bike lane mileage.

The Chicago Department of Transportation's website states that Chicago currently has more than 200 miles of on-street protected and buffered bike lanes, plus streets with shared-lane markings ("sharrows.") But a recent Active Transportation Alliance’s analysis calculated that Chicago has a little less than 30 miles of barrier-protected bike lanes, the type of bikeways that are most effective for encouraging more people to bike, thereby reducing emissions. I was motivated to do more research on San Jose’s bike plan and found it to be a great model that CDOT would do well to emulate in order to reboot our existing Chicago Streets for Cycling Plan 2020.

San Jose’s Better Bike Plan 2025 acknowledges that the vast majority of San Jose’s on-street bikeways are not comfortable for most residents, given that many people would prefer to not ride without physical protection from cars. According to city-collected data, 75 percent of San Jose residents do not feel comfortable using bike lanes without barriers. Back in 2018 San Jose created the Better Bikeways initiative, an effort to rapidly build low-cost, low-stress bikeways that “appeal to a wider audience” and include more separation from vehicles.

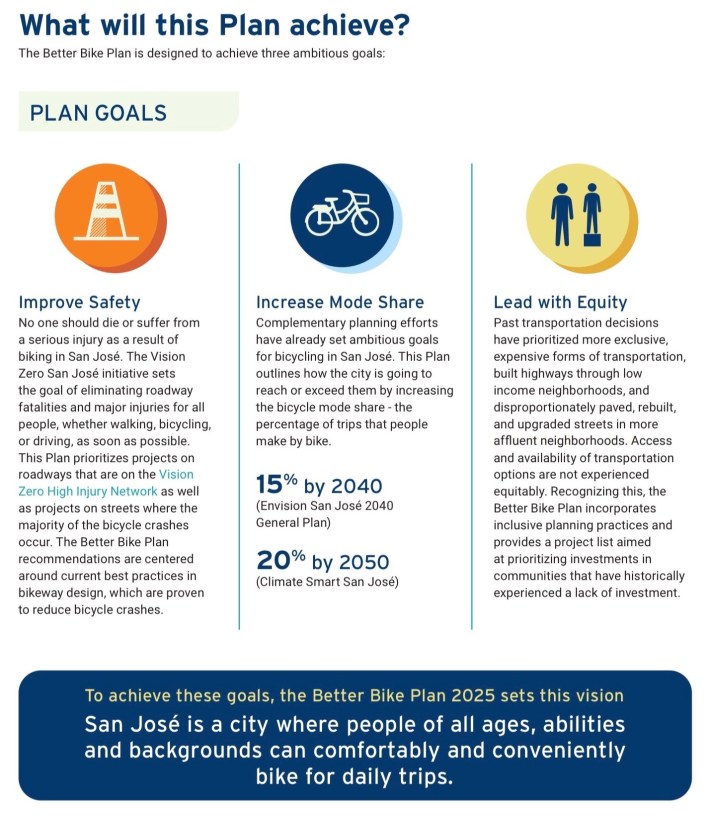

The 2025 Better Bike Plan aims to increase the Better Bikeways initiative to neighborhoods surrounding downtown (which benefited from the first iteration of Better Bikeways) and other areas of the city. The Better Bike Plan is also aligned with the city’s efforts to have 15 percent of all trips be made by bike by 2040 and the city’s Vision Zero Action Plan. Just as important, the plan acknowledges past transportation planning decisions that have harmed low-income communities of color.

Many Chicago sustainable transportation advocates are aware that the city’s Streets for Cycling Plan 2020 didn't come anywhere close to its goal of providing "a bicycle accommodation within a half-mile mile of every Chicago resident" by the year. Less than half of the 645-mile proposed network has materialized.

And I could help noticing that almost everyone in the photos of the community input meetings for the Streets for Cycling plan published in the document was white, and most of them were men. While the plan didn't mention the demographics of the attendees, that made me wonder whether the documents really reflects the needs of the larger Chicago population, which is about two-thirds POC.

I’ve always wondered how representative a plan the Streets for Cycling 2020 plan was given the outsized representation of White males in the photos. I am unsure of the demographics of folks who participated since it was not mentioned in the plan. I appreciated the fact that San Jose made a point of soliciting feedback from “historically underrepresented groups” and made it a priority to “focus on identifying communities that exist at the intersection of limited mobility and barriers to public participation.” These groups were listed as:

- Lower-income residents and workers

- Communities of color

- People with limited English proficiency

- Youth

- Seniors

- People with physical disabilities

I often wonder how different our streets would look if we were designing with the needs of these groups at the forefront of planning priorities. City and neighborhood planning processes should required to be representative of the demographics of the larger population, with a commitment to soliciting input from groups that are traditionally not engaged by the city.

I appreciated that the initial phase of San Jose’s Better Bike Plan started with gathering input from residents through neighborhood events, community group meetings, business group meetings, and pop-up events. They asked residents which streets should be improved first, where people like to bike, what bike-related issues could stand to be improved, and what would help them bike more? Targeted engagement with underrepresented groups asked what policies were important, preference for bicycle facilities, and what destinations were important when it comes to biking access.

Chicago's outreach for the 2020 Bike Plan kicked off with an open house meeting that took place downtown in December 2011. Reported attendance was 160 people. According to the plan, public meetings were held in early 2012 at 3 locations; attendance numbers were not reported. Community Advisory Groups, led by two or three volunteers, were formed "to identify the best streets for future on-street bikeways" in their respective location. Over a six month period, the volunteers were able to engage 200 Chicago residents.

In comparison, I couldn’t help but be impressed by San Jose listing their community engagement numbers: over 600 people engaged in person (pre-COVID), 270 online comments, and over 3,5000 people reached online via digital meeting. Clearly there’s room for improvement when it comes to the community engagement process for developing a better bike plan for Chicago. There's also been a lot of great development in the past few years in terms of best practices to engage underrepresented groups who typically face barriers to public engagement. In order to create a truly inclusive bike plan and one than can gain political support, it must be crafted by a large and representative sampling of Chicago residents. A bike plan impacting the lives of millions in Chicagoans should have consulted more than hundreds of people. San Jose has a fraction of the population and managed to create what I think is a great bike plan.

In addition to robust community engagement, San Jose analyzed their streets in terms of stress experienced while biking and connectivity via bike. I was impressed with this analysis because many of Chicago’s streets that have painted bike lanes are quite stressful to bike on, especially if they’re on a major street. There are also frustrating gaps in what could be a cycling network and a lack of continuity when it comes to design. San Jose acknowledges they must do more to make biking comfortable and safe. I would love to see Chicago do the same and develop an enforceable plan to create a low-stress citywide biking network.

A lot has changed since in our city's bicycling environment since the Streets for Cycling 2020 Plan was released. Most significantly, the Divvy bike-share system launched in 2013 and has expanded greatly since then. And just during the last seven months, the COVID-19 pandemic we've seen a large increase in bike sales; a huge increase in Divvy ridership as e-bikes were rolled out and the system was expanded to the Far South Side; and an increase in women cycling according to Strava data.

If CDOT was a well-funded, responsive, and nimble agency, it could be engaging with new riders and responding to their needs. CDOT and the Illinois Department of Transportation could be asking new riders about their experiences, and what they need to feel safe and comfortable on the road. CDOT could be rapidly installing quick-build projects and soliciting feedback as it goes. Along with robust engagement, the political will to build the type of biking infrastructure and invest in creating a cycling culture necessary to keep people riding and grow cycling numbers is critical. We can build public support by putting forth a bold vision for biking informed by truly engaging with Chicagoans at the intersection of a climate change, mobility justice, and COVID recovery.

Unlike the Chicago bike plan, San Jose’s document has a follow-through section. Wow, a plan to ensure the feedback received is actually implemented! Along with a strategy to fund the identified improvements, San Jose states they are “committed to growing the diversity of people that bike.” To that end, the city commits to ongoing efforts to develop a multi-faceted public relations campaign to share the benefits of cycling, organize car-free "ciclovia" events and social rides, and support individuals or organizations to build a bike culture for underrepresented groups.

At some point it seemed Chicago was on track to create a more diverse cycling community through neighborhood-based sustainable transportation outreach and encouragement programs like Go Bronzeville. As I looked into Go Bronzeville, I learned that it was a federally funded program. As advocates urge the city to invest in sustainable transportation, we must also envision the type of programs necessary to grow cycling ridership. Infrastructure is a huge part of the path forward but so is programming to educate and empower new riders. Los Angeles’ CicLAvia comes to mind as programming that can provide a safe environment for new riders and an opportunity for people to experience the benefits of car free spaces. While Chicago's ciclovia program, organized by the Active Transportation Alliance, failed due to lack of financial and organizational help from city officials, Chicago would do well to properly fund and support a new one, plus other programming that can help make cycling accessible.

There’s more I could say about the San Jose Better Bike Plan and I encourage you to check it out for yourself and consider how we can create a better bike plan here in Chicago. CDOT hasn't announced that it will be updating its 2020 plan, but I am cautiously optimistic that the department can equitably increase sustainable mode share if it gets serious about doing so. It is somewhat encouraging that CDOT is creating surveys to collect resident input, and I would love to see efforts to increase outreach in Black and Brown communities.

In September CDOT cancelled their quarterly Mayor's Bicycle Advisory Committee meeting. In an email to MBAC partners, CDOT shared that they are "undertaking a strategic plan to revisit and realign the agency’s values, mission and delivery processes. The entire agency is involved in this plan, which will touch every aspect and role that CDOT engages in. CDOT also wants to make sure that the plan sets the tone for and advances equity," creates closer relationships with communities, and creates long-term strategies for mobility justice. It will be interesting to see how the city's budget supports or doesn't support this vision coming to fruition in the near future.

Follow Courtney Cobbs on Twitter at @FullLaneFemme.