Yesterday the Active Transportation Alliance outlined four barriers to creating more protected bike lanes in Chicago and solutions to overcome those obstacles. Along with a blog post regarding the four barriers, ATA is asking residents to email their local officials urging them to support planning and funding for a protected lane network. Let’s dive into the 4 barriers:

Lack of dedicated capital funding

There are a number of existing city policies and plans to create safer conditions for biking and walking, such as CDOT’s Complete Streets policy, Chicago Streets for Cycling Plan 2020, and Vision Zero Action Plan, but these plans have fallen flat due to a lack of dedicated funding. Currently, city officials rely on limited, local discretionary funds and inconsistent, highly competitive state and federal grants to fund protected lanes. A dedicated local source of funding is needed to create high-quality biking and walking infrastructure.

ATA proposes an annual $20 million Chicago Safe Streets Fund with a focus on high-crash corridors on the South and West side. Mayor Lori Lightfoot actual committed to doing just this during her election campaign -- it was one of the planks in her transportation platform --but so far has taken no visible action.

Staffing shortage at CDOT

Protected lanes require design and engineering resources that are currently in short supply. ATA writes that the Chicago Department of Transportation “currently has one full-time city planner dedicated to advancing Vision Zero infrastructure projects and the city’s bike and pedestrian program.” Consultants that come and go are assigned additional work. The revolving door of consultants does not create an the environment necessary for long-term planning. As we look at other cities that are lapping Chicago when it comes to the creation of protected bike lane networks, those cities have well-staffed departments of planners and engineers who are committed to creating safer streets. Our spending priorities must match the rhetoric that we support safer and more sustainable streets. ATA’s solution to this problem is the funding of several new full-time positions at CDOT, including more bike, pedestrian, and transit planners, and at least two new traffic engineers.

Lack of cooperation from Illinois Department of Transportation on state-jurisdiction roadways

In Chicago, many of the major streets that connect to popular destinations are state-controlled. This results in many of the key routes identified in the Streets for Cycling Plan being essentially off the table for protected lanes, because IDOT has traditionally been loathe to make changes to streets that might cause any inconvenience to drivers. State-jurisdiction streets routinely top the list of high-crash streets, most of which are located in Black and Latinx communities.

The state of Illinois has a Complete Streets law but it lacks teeth. The Illinois Complete Streets Policy allows IDOT to use poorly defined “exceptions” to get around the rules. ATA also states the 2007 law has never been evaluated or reviewed to determine whether it’s leading to the construction of more safe streets infrastructure, including PBLs. Despite lobbying in 2019 that lead to protected lanes being added to the IDOT design manual as a recommended type of bikeway, the department rarely actually approves them.

This issue was apparent in the recent redesign of North Avenue in Humboldt Park. While the four-lane street got new crosswalks, pedestrian islands, and non-protected bike lanes, this was a missed opportunity to create a truly safe biking corridor by installing protected lanes. ATA proposes passing legislation to strengthen the state's Complete Streets law, and electing more state officials who support sustainable transportation in order to advance IDOT reform.

Community and political opposition

ATA acknowledges the perception among bike advocates that community opposition is the main reason more bike lanes don’t get built. In reality, structural barriers prevent most projects from reaching the final approval stage. However, opposition from residents, business owners, and aldermen does sometimes derail protected lane projects.The city’s outreach resources are limited so the people and organizations with the time and energy to speak out on their own have the most influence under the current process.

Often the voices of residents in high-need Black and Brown communities on the South and West side are overlooked. ATA sees community-centered planning as crucial to designing and building effective projects. They propose a number of solutions to ensure that the community input CDOT receives is reflective of the community:

- Strengthen the community outreach processes through the lens of a comprehensive plan focused on racial equity.

- Leverage existing community infrastructure like special service areas, neighborhood groups that serve as delegate agencies for the city, and park advisory councils.

- Conduct Racial Impact Equity Assessments for major capital projects, like road reconstructions.

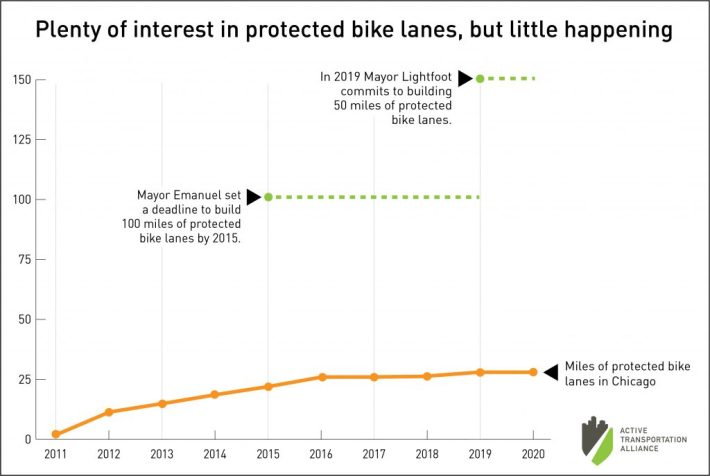

Together, the Emanuel and Lightfoot administrations promised more a total of 150 miles of protected bike lanes, but so far we haven't even broken 30 miles. We cannot expect to significantly increase the number of people biking for transportation or recreation without creating safer conditions to do so. Along with building more protected, we must ensure that they are equitably distributed around the city.

Click here to email your elected officials and ask them to support protected bike lanes.

Follow Courtney Cobbs on Twitter at @CourtneyCyclez.