While Metra has regained some of the ridership it lost since Illinois' Stay at Home order kicked in on March 21, ridership is still nowhere near normal. It won’t be normal for quite some time.

That was a major takeaway from the August 19 meeting of the Metra board. The mid-year ridership and financial reports, which are normally routine, have taken on a whole new significance in light of the pandemic. At the moment, ridership seems to have plateaued at around 10 percent of the 2019 numbers, while CTA and Pace ridership has been closer to 20-30 percent of their respective 2019 ridership numbers. And Metra expects that, even after a vaccine or an effective treatment for COVID-19 is found, it could take as long as three years for ridership to return to last year’s levels.

At the moment, Metra is still trying to reduce expenses and optimize services to get as much as it can out of declining fare and tax revenues. The transit agency is doing market research to figure out the best way to get more riders on board.

As Lynnette Ciavarella, Metra’s Senior Division Director of Strategic Planning & Performance, explained to the board, the transit agency was actually doing better than last year until March. “All indicators were that we would be on track for another positive year,” she said.

But as March rolled on, Metra started seeing the effects of the pandemic as conventions were cancelled and many Chicago companies had their employees worked from home. The Stay at Home order shut down all businesses that weren’t considered essential. Over the next few months, Metra cut back the schedule on all lines. To reduce conductors’ risk of infection, Metra stopped having them collect fares in April.

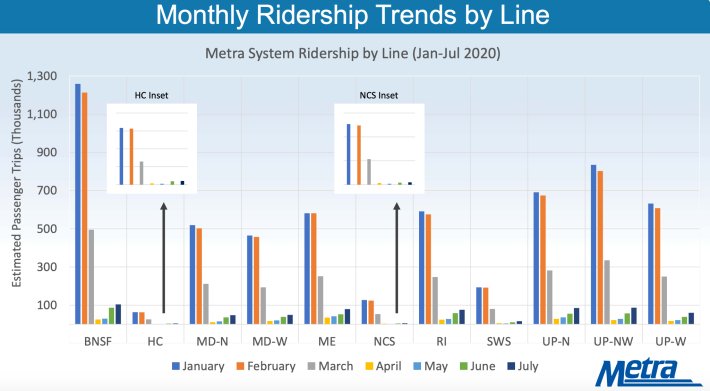

Ciavarella noted that, while ridership plunged on all lines, the Metra Electric District line fared slightly better than others, becoming the highest-ridership line in April and May, ahead of the usual first and second-place holders, the BNSF and Union Pacific Northwest lines. The MED stands out because of how many of its stations serve the city, and because it's the only line with an entire branch that lies completely within the city limits. If the service wasn’t twice as expensive and far less frequent than the ‘L’ and buses, it would been a much more popular transit option.

In April and May, CTA buses were free, while ‘L’ lines still charged fares. The MED’s schedule was reduced, but not quite as much as the other lines. That may have made the line a more attractive option than before. The fact that the MED serves many working-class South Side communities where residents are more likely to have to show up to work in person than in more affluent areas probably didn’t hurt, either.

During the same period, the Union Pacific North Line was doing relatively well coming in second place in May. The line serves Kenosha, Wisconsin, where most statewide COVID restrictions were lifted mid-May after the Wisconsin Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional. It’s hard to say whether that had much of an effect on ridership (since it wasn’t doing that much better than the rest of the line), but I couldn’t have been the only Chicagoan who took the line to Kenosha back in late May out of sheer curiosity.

Another factor that may be a factor in why UP-N ridership didn't drop quite as much as other lines is that the Ravenswood, Rogers Park, Main Street, and Davis Street Metra stations are all located within walking distance of ‘L’ stations. With Metra being free while the ‘L’ wasn’t, it may have become a more attractive alternative (I used Metra to get from Rogers Park to Evanston on a number of occasions for precisely that reason).

As the state and the city relaxed some restrictions in early June, Metra began reversing some of the service cuts, and conductors started checking tickets again. (However, conductors on the three Union Pacific lines still aren't doing much fare-collecting to this day thanks due to the ongoing legal spat between Metra and the Union Pacific Railroad). The ridership increased, with BNSF and Union Pacific Northwest retaking first and second place, but it was still at around 10 percent of what it was pre-pandemic.

Under the Restore Illinois plan, the state will remain in Phase IV until a vaccine or an effective treatment is found. Assuming Chicagoland doesn’t get rolled back to Phase III due to a jump in cases, Ciavarella said that the agency expects the ridership to gradually reach around 30 percent of the 2019 ridership by the end of 2020.

Thomas Farmer, Metra’s chief financial officer, emphasized that, even with ridership rebounding, the transit agency “was still running largely empty trains.” And he warned that, even after the vaccine and/or treatment is found, it may take 1-3 years for ridership to return to 2019 levels.

“After the restrictions are lifted, we have to understand the new realty of who is our potential Metra customer,” Farmer said. “We have to figure out what people want. We have to figure out what safety measures they believe they need.”

He noted that, even before the pandemic, Metra has been concerned about how increased telecommuting would impact ridership. After the pandemic, some of the new telecommuting may be here to stay. And Farmer said that his conversation with large Chicago employers suggest that, whenever happens with the infection rates, “at the year end many people will still be working from home.”

Another factor that may impact ridership is that, as offices reopen, lighter traffic and cheap gas may lead commuters to take their cars to work instead.

For now, Farmer said, Metra ridership depends on several factors it can’t control: whether more schools and colleges have some in-person learning later this year, whether there will be more hiring, and whether some companies bring employees back to the offices.

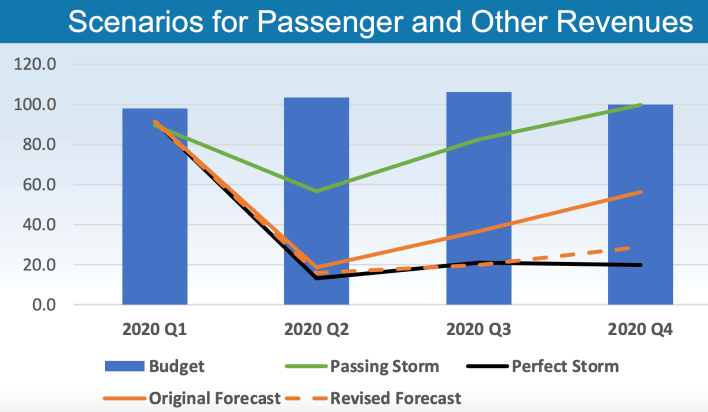

Farmer also touched on Metra’s finances. The transit agency estimates that its sales tax revenue will be down 20-25 percent this year. As of June 2020, revenue from fare collection, leases, and advertising was down by 20 percent, and Farmer said that he expects passenger revenue to decline by 67 percent before the end of the year. In 2020-2021, he expects Metra to lose $464.9 million in passenger revenue and $217.6 million in sales tax revenue. While he expects the passenger revenues to increase in 2021, the sales tax shortfall would actually be worse that year.

Federal CARES Act transit funding and Metra's running fewer trains helped to mitigate these losses, but, Farmer emphasized that the CARES Act funding will run out by mid-2021, assuming revenues and expenses stay at the same level. Along with the Regional Transit Authority, the CTA, and Pace, Metra recently published an open letter calling for $32 billion in new federal transit funding to be distributed nationwide.

If there is any upside of the current crisis, Famer said, it’s that Metra has the opportunities to “experiment with optimizing labor force, service patterns and fare collections.” He said that Metra is currently doing market research to figure out the best way to regain old riders and gain new ones. And the railroad will be looking to better respond to ridership demands during the pandemic, including looking at ways to get commuters to suburban workplaces, whether they are coming from Chicago or other suburbs.

“[To make the funds last], we need to do everything we can to move revenues up and costs down,” Farmer said. “That means focusing on increasing ridership and being more efficient.”

While Metra Executive Director Jim Derwinski readily acknowledged that the transit agency has tough times ahead, he tried to end the meeting on an upbeat note. “COVID will be behind us someday,” he said. “We will play a key role in recovery of our region And we will rebuild confidence in our service.”

Follow Igor Studenkov on Twitter at @istudenkov.