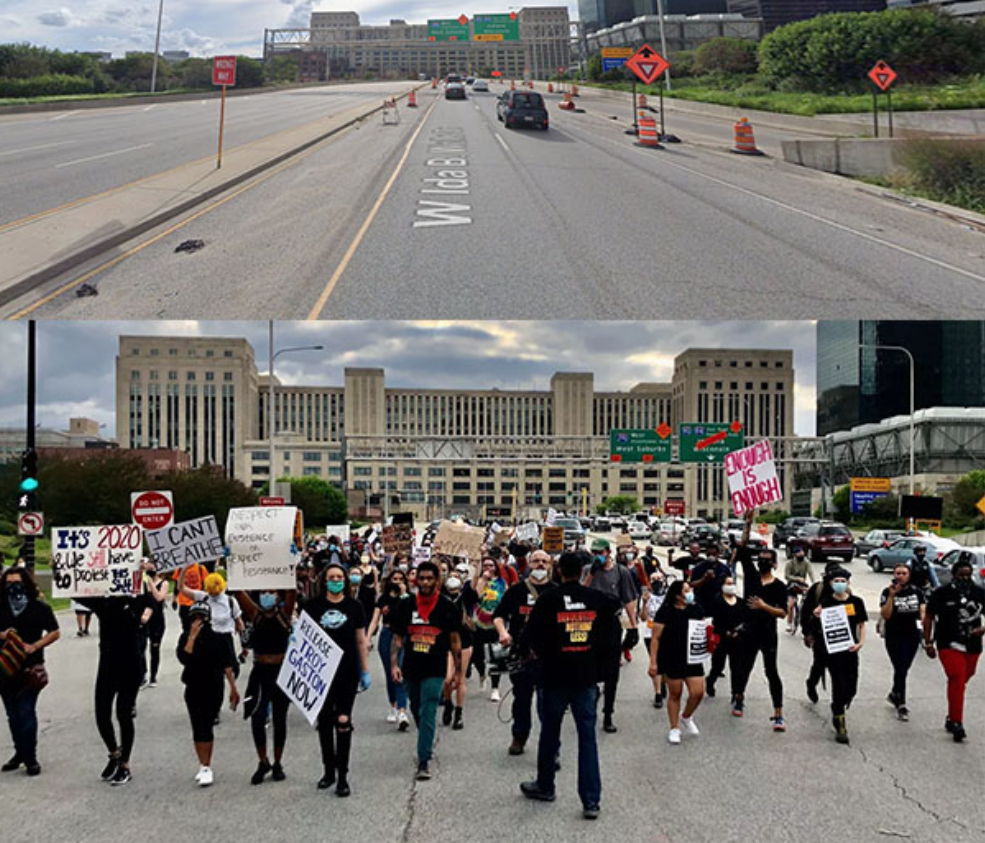

After the police murder of George Floyd, thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and to call for police reform or abolition, among other things. Although occupying the street during a protest is often meant as disruption, intended to inconvenience road users and halt mobility, maybe this kind of occupation can also act as a roadmap for public space and street design. We are seeing two distinct modes of street reclamation in the wake of George Floyd’s death: road repurposing and placemaking.

Road repurposing, the idea of using streets for activities other than driving cars, is not new. Cities like Bogotá and Mexico City run weekly Ciclovías (Spanish for bikeway) where major thoroughfares are closed to motor vehicles and opened to pedestrians and cyclists. Chicago hosts a similar event each year, closing Lake Shore Drive to drivers and opening it to cyclists for Bike the Drive (although sadly the event was cancelled this year due to the pandemic.)

The Copenhagen Strøget, a former vehicle road, is a classic and successful example of street repurposing. Now fully pedestrianized, the central avenue sees heavy foot traffic year round. This is also demonstrated in events like street fairs or concerts, where roads are repurposed for human-scaled use and leisure. Walking in and occupying the streets in protest, too, is road repurposing.

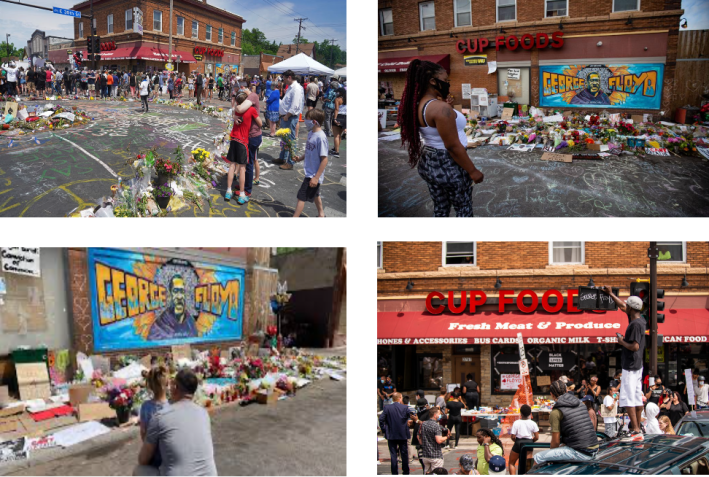

Placemaking is also not a new concept. Creating inviting public spaces through intentional urban design is a goal widely touted. A cheap, easy, and common method in placemaking is artwork. Simply by using paint, streets and facades can be transformed into welcoming, interesting destinations. Placemaking through artwork can now be seen throughout the country in murals and paintings to commemorate the lives the many Black people killed by police.

The most palpable and poignant example of this is seen at the intersection in Minneapolis where George Floyd lost his life. The pavement and surrounding walls have been filled with memorializing artwork and people are gathering in the street.

This placemaking comes from tragedy and pain. But it is placemaking. People are together. People have made this public space their own, what they want it to be. This corner is now a place.

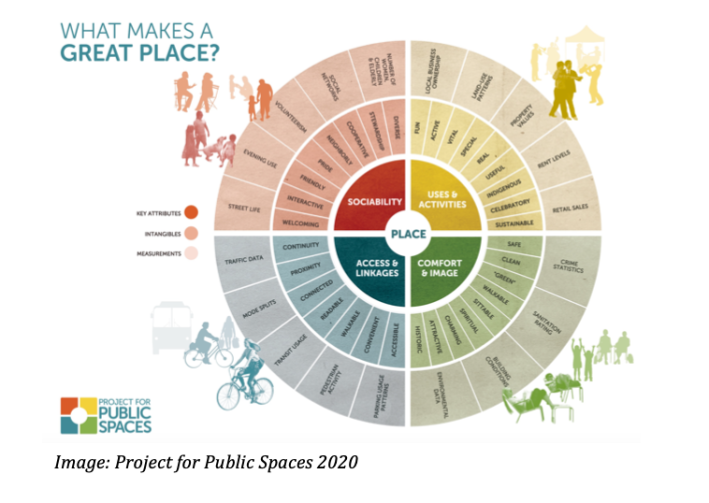

In the Project for Public Spaces guidelines for ‘What Makes a Great Place?’ we can see how locations have become, even if only temporarily, great places. Specifically the ‘intangibles’ of the categories of Sociability, Uses & Activity, and Comfort & Image are now seen in places where they weren’t present before. Newfound pride, neighborliness, activity, interactivity, vitality, celebration, walkability, sittability, attractiveness, and spirituality are clearly present.

Protesting is not new. The desire to reclaim the streets is not new. But these specific, massive, and distinctively widespread protests have happened during the COVID-19 lockdown, an event that in itself has caused many cities to rethink street use. Streets are being opened to increase the pedestrian space needed for social distancing, and make room for outdoor restaurant dining, and some cities like Paris are considering permanently converting roads from vehicle to pedestrian and bicycle use.

And now in the George Floyd protests, as with all protests, we see people asserting their right to be in the streets. To occupy and make use of that space. These protests are work; they are a necessity. No one is protesting because they’re trying to take back streets from cars or placemake, but they’ve inadvertently highlighted how much better it is to use public space in a more human-centered, non vehicle-dominant way.

On a fundamental level we are seeing people using streets in ways that traffic engineers did not have in mind: for uses other than driving. We are seeing placemaking and community building. Although reclaiming streets for human-scale uses is not really a novel idea, the George Floyd protests are one more example of people converting public space to their desired uses. As we reimagine cities during COVID-19, it’s time to redesign our streets and public spaces to better reflect the needs and wants of residents.

People have a latent desire to take back streets in their own way and for their own purposes. The response to police brutality and killings has been an example of people exercising that desire, as demonstrated in the common protest chant, "Whose streets? Our streets!" These instances of road repurposing and placemaking are born from pain and anger yet they have brought communities together and created beauty. Using streets and spaces shouldn’t just occur in the wake of tragedy—it should be intentionally planned and designed into our cities.

A note from Streetsblog Chicago assistant editor Courtney Cobbs: In an ideal world people would not need to protest in the streets, especially not protest to demand the end of state killings at the hands of police officers. Recent conversations around race and planning have highlighted the need to substantively involve residents in the planning of their communities. We must go beyond simply informing communities that there are proposed changes and work towards asking residents what they feel their communities need. Placemaking ideally wouldn't occur in response to a life that was taken too soon, but rather as as a way to create community and foster joy. Planning alone will not be enough to change Black and Brown folks' relationship to the built environment.