How do we promote efficient and equitable transportation during and after the pandemic?

8:46 PM CDT on April 24, 2020

Walking and biking in Chicago’s Douglas community area. Photo: John Greenfield

Yesterday the Illinois Environmental Council presented the webinar "Walking and biking during COVID-19," featuring Audrey Wennink, transportation director at the Metropolitan Planning Council, and Lynda Lopez, advocacy manager at the Active Transportation Alliance (and a former Streetsblog Chicago reporter.)

Obviously the pandemic has had huge impacts on the way Chicagoans live, work, and travel. The rules of Illinois' Stay at Home order are evolving based on what researchers learn about the disease, as well as the rising or falling number of cases. For example, yesterday Governor J.B. Pritzker announced that all residents two and over who are medically able to do so must wear face masks or coverings while visiting indoor public spaces like stores.

Many Chicago residents have stopped commuting to an office and are instead working remotely. On top of that, due to the possibility of viral exposure, many people are avoiding transit altogether. As such, CTA ridership has plummeted by a staggering 80 percent from its typical 2 million rides a day, and Metra and Pace are seeing similar drops. The agencies have taken steps to try to protect workers and riders, such as extra sanitation measures, and rear-door boarding on CTA buses.

Because walking and biking offer an option for socially-distanced transportation, they're more important modes than ever. That's doubly true because they're an opportunity to get fresh air and exercise, and take a mental health break, at a time when so many people are cooped up in their houses. But we need to make accommodations for pedestrian activity and cycling so that people can do them safely, with the required six feet of space from other people.

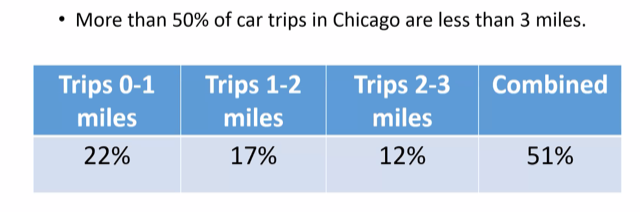

"How do we make biking and walking more safe and appealing?" asked Wennink. "Should there be considerations for temporary shared streets, temporary bike lanes, more space for bike parking, including in offices, slowing down automobile traffic, or plans to convert parking lanes to expanded pedestrian paths?" She added that Chicagoans often rely on cars for relatively short trips: More than 50 percent of local car trips are under three miles and 22 percent are less than a mile. Many of those journeys could easily be done on foot or bike, if conditions for walking and cycling were safe and pleasant.

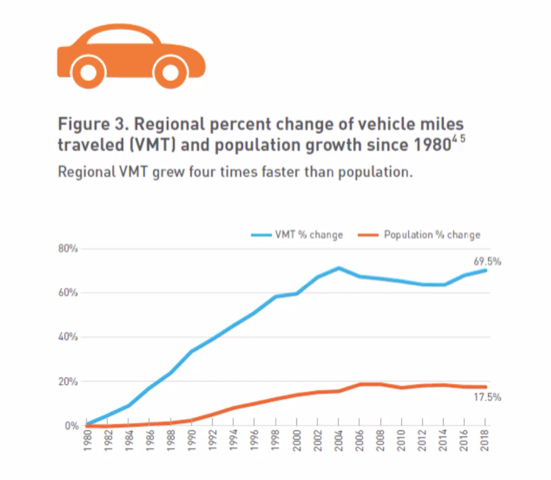

However, between 1980 and 2018, when the population of the Chicago region grew by 17.5 percent, the number of vehicle miles traveled by motor vehicle in the region rose by a whopping 69.5 percent. About 77.4 percent of Chicagoland residents currently drive to work. The increase in driving has been largely driven by land use policies that lead to suburban sprawl, as well as decision-makers' focus on road expansion, rather than encouraging sustainable modes.

Wennink noted that SUV ownership is popular in the U.S. partly due to the low cost of gas in our country compared to other nations. However, she added that "about 25 percent of Chicago households and 13 percent of regional households do not own a car due in part to the $8,500 yearly maintenance vehicle costs reported by the American Automobile Association." In addition, she said, road maintenance costs are running at $28,000 per mile nowadays.

Our region's car-dependence has major impacts on safety, Wennink said. About a 100 people a year are killed in motor vehicle-involved crashes in Chicago, and roughly 40 of them are pedestrians.

While driving is down about 50 percent in Chicago during the pandemic, Wennink asked, "What will happen when we are allowed to move around again?" She noted that even after the Stay at Home order is lifted and workplaces reopen, many people may be apprehensive about riding transit, which could lead to more driving than ever -- if we aren't proactive about encouraging walking and biking as alternatives.

Cities all over the country, from New York to Salt Lake, have been experimenting with opening up streets for walking and biking during the pandemic, with varying degrees of success. Wennink noted that Oakland's "Slow Streets" program, which involves banning through traffic on 74 miles of side streets but allowing local traffic, at a low cost, with no additional policing, has promise. However, Chicago has no plans to do any kind of open streets program.

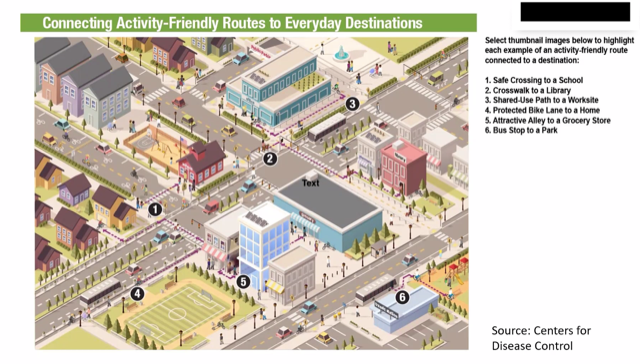

According to Wennink, Chicago currently has about 200 miles of bikeways, including physically protected lanes, painted lanes, and streets with "sharrows," bike-and-chevron symbols. The goal of the city's Streets for Cycling Plan 2020, released in 2012, was to create a 645-mile bike network by -- right about now -- which obviously didn't happen. Meanwhile, the city has 4,000 miles of streets. Wennink we need more protected lanes, and other "8-to-80" pedestrian and bike facilities, "so people of all ages feel comfortable walking and cycling."

Wennink noted that the costs of expanding pedestrian and bike access is a fraction of the expense of car infrastructure. She said the estimated price tag for the planned reconstruction and expansion of I-294, I-290, and I-55 is $7.4 billion, while 100 miles of bikeways cost a mere $12 million. She added that walkability will become increasingly important as Baby Boomers age and Chicagoland has a larger population of residents who don't drive.

Lopez discussed the “Mobility Justice and COVID-19” statement recently published by The Untokening. The group calls itself “a multiracial collective that centers the lived experiences of marginalized communities to address mobility justice and equity.”

"History plays a significant role in the way cities are developed and in considerations for different policies," Lopez noted. For example the role of policing had historically had a huge impact on the freedom of Black and Latinx residents to move freely about cities, and that issue is an ongoing problem.

Lopez argued that our top transportation priority during COVID-19 should be to support essential workers. She noted that these people are often putting their lives on the line to keep our society functioning.

"There have been calls all around the nation, in Chicago to keep trails open for recreation" during the pandemic, Lopez stated. "Some people might see this as tone-deaf if we are not considering that there are still a lot of people dying from this pandemic."

Here in Chicago Kyle Lucas, an essential worker with HIV, who can't risk viral exposure on transit, has launched a petition to reopen the Lakefront Trail for bike commuting and open streets for walking and biking, which has garnered over 1,000 signatures.

"How are we approaching this conversation honestly?" Lopez asked. She noted that about 70 percent of people who have died from coronavirus in Chicago have been Black.

During the webinar Lopez said that the Active Transportation Alliance is not opposed to open streets. But she argued, "It is a challenging concept to want to fully advocate for because of the [Stay at Home] mandate and what are the equity implications for supporting these policies."

Lopez discussed how the issues of environmental justice intersect with transportation access. For example, the recent demolition of the Crawford coal-fired power plant's smokestack in Little Village raised a thick cloud of irritating dust in nearby POC communities, exacerbating respiratory issues during the pandemic and making walking and biking risky.

Lopez also talked about what's needed to encourage more people to walk and bike, including considering barriers to bike ownership and use. She noted that safety means different to different people. For example, people in Chicago's lower-income communities of color may make decisions about travel based on issues that may be off the radar for wealthier and/or white residents, such as the potential for police harassment, immigration crackdowns, or street crime. Therefore, we need to prioritize getting diverse points of view on transportation planning and policy issues.

The Untokening plans is hosting a program called "Community Resilience and COVID-19" on a bi-weekly basis as part of its ongoing "Transformative Talks" series. The webinars will take place on May 1, May 15, May 29, June 12, and June 26 at 2 p.m. CST. According to the website, participation by BIPOC (Black and Indigenous People of Color) is prioritized, and people from other marginalized demographics, such as women, LGBTQ folks, and people with disabilities, are also encouraged to attend.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Chicago

Since COVID, Pace ridership has fared better on major corridors and in north, northwest suburbs than in south, west ‘burbs

The suburban bus system's top five busiest routes largely maintained their ridership rankings.

Due to incredible support from readers like you, we’ve surpassed our 2023-24 fundraising goal

Once again, the generosity of walk/bike/transit boosters is fueling our reporting and advocacy.