The days of using transit and ride-hail, except as a last resort for essential trips, seem like years ago. Transportation agencies and ride-hail companies are struggling to stay afloat during the pandemic, as they see fewer customers and a drastic drop in revenue. Social distancing is basically impossible for Uber and Lyft drivers and passengers.

While those of us who can are mostly staying home and avoiding public places, the CTA, Metra, and Pace are continuing to operate so essential employees can get to work. On April 9 the CTA began requiring rear-door bus boarding to reduce drivers' viral exposure. Bus service is currently free, but the agency is currently installing Ventra card readers inside the back door, so within a few weeks riders will be expected to pay fares again. The agency has also added capacity to busier routes to prevent dangerous crowding, and allowing bus operators to run express once there are 15 people on a regular bus or 22 riders on an articulated vehicle.

Uber and Lyft have stopped offering pooled rides in the U.S. and Canada markets to reduce the chances of viral spread between passengers and drivers. But social distancing, maintaining six feet from others, inside most ride-hail vehicles, where you’re basically breathing the same air as the driver, is nearly impossible. So it's best to avoid this mode during COVID-19 unless you really have no other choice.

As transit and ride-hail companies are currently facing major revenue losses, the big question is, how will they bounce back after the pandemic is over? Working together can be a start.

According to a new study by the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Policy at DePaul University, transit agencies could benefit from partnerships with Lyft, Uber and Via for on-demand services to tap into new markets, which would help with recovering from the current crisis. The study, published April 14 and called “21 Key Takeaways from Partnerships between Public Transit Providers and Transportation Network Companies in the United States,” explores the risk and rewards of partnerships involving ride-hail providers.

Mallory Livingston Shurna, an independent consultant on shared mobility who co-authored the study with Chaddick Institute director Joseph Schwieterman, said the study’s goal was to look at the problems transit agencies are facing, see what new challenges have emerged, and find out what agencies have learned so that more collaboration can take off. “We are not advocating for partnerships in all cases, but [rather to] fill gaps in knowledge,” Shurna said at a public webinar about the study on April 16.

The analysis looked at two types of programs: Transportation-as-a-Service Programs, where transit agencies operate vehicles based on a the agency’s contractual requirements, and subsidies are typically paid either per ride or vehicle hour; and Software-as-a-Service Programs, in which an agency manages vehicle operation using technical resources provided by a ride-hail company. “These programs run the gamut from discounts for rides to bus or train stops to eliminating ‘transit deserts’ or catering to disadvantaged populations,” the authors wrote.

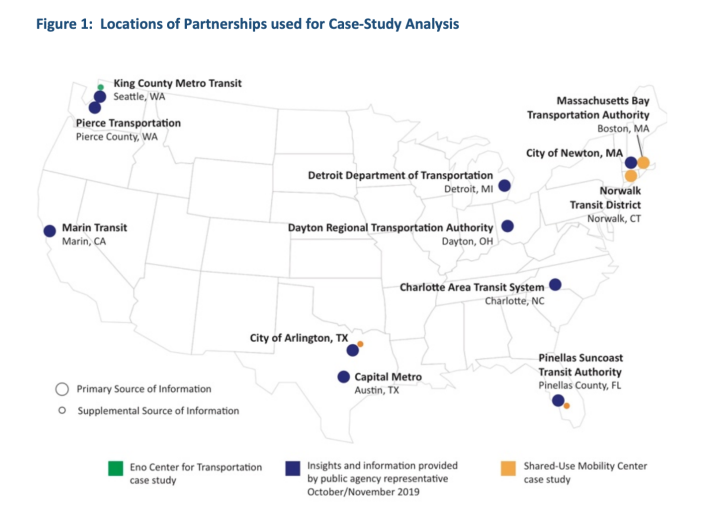

The study used 10 existing programs in smaller cities around the country directly involved in ongoing or discontinued partnerships, as well as discussions with Uber and Via representatives between October and December 2019, as case studies for better understanding this growing partnership option. Among the on-demand programs reviewed were the Greater Dayton Regional Transit Authority’s Connect On-Demand program, which offers free Lyft and Uber trips to residents affected by reductions in bus service; Detroit’s NightShift program, which offers discounted Lyft trips to certain transit stops at off-peak times; and Marin County, California's On-Demand program, which was primarily intended to serve the elderly and people with mobility challenges, but makes discounts available for all passengers traveling to and from certain transit stops.

Using these pilot programs, the study aims to address three key mobility problems: providing first/last mile service by closing the gap between bus stops or train stations and the traveler’s origin and/or final destination; responding to reductions in fixed-route service or complementing service on low-frequency routes; and improving mobility for seniors, people from low-income areas with less access to transportation, and people with disabilities.

Out of the 21 takeaways, Shurna said, a few stand out as highlighted trends among the case studies that can be pathways for new agency partnerships. On-demand programs are poised to become more common in rural and suburban areas because transit companies might see less demand post-pandemic. She added that paratransit options that match companies to customer capabilities will also become more popular in suburban areas. “Agencies are seeing opportunities for cost-saving for on-demand programs tailored toward paratransit.”

Another major takeaway was that the demand for wheelchair-accessible vehicles for programs not designed to serve people with disabilities was lower than anticipated. Shurna attributes that to the lack of trust and awareness between community members and agencies. The authors argue more communication, brand awareness and patience can lead to better serving people with disabilities and other marginalized communities. You can view all of the takeaways here.

The researchers found that when rides are subsidized by a fixed amount per trip — often a flat rate — it's easier for consumers to understand how the payment system works. Shurna said this model would be best for large cities. But while subsidy-only programs are often the lowest-cost option among public partnerships, they routinely come at the expense of access to driver and customer information, and the ability to set certain performance standards.

During the webinar, co-author Schwieterman said “there is a myth that agencies are fighting for data,” but added that some transportation experts with the pilot programs noticed that access to data was an issue. Stacy Matlen, a senior mobility strategist involved Detroit’s NightShift program, said getting route and user data from Lyft to improve the program has been a challenge. “It’s been an ongoing battle, but we were able to work around these challenges,” she said.

Penny Grellier, the community development administrator for On-Demand Limited Access Connections for Pierce Transit in Lakewood, Washington, said her program has seen some success. She predicts that these partnerships will grow and become more popular after the pandemic is over. “Post-coronavirus, we are going to see more [programs] because of the sheer financial realities for transportation services."

Update 4/25/20: The CTA provided the following statement.

While this study was made public a little over a week ago, any time new studies regarding mobility are issued, we examine them closely. We are always open to discussion with the [ride-hail] companies.

Public transit will always be essential to the City of Chicago. Like transit agencies across the country, we do not yet know what the ‘new normal’ will mean for public transit. As CTA has always done, we will continue to look for the best, most effective ways to provide public transit and serve the region’s transportation needs.