As a teen I lived on a block of West Rogers Park with many African and Caribbean immigrant families, and I took the bus and ‘L’ to get to high school. Although I loved where I grew up, my block never felt bustling, Western Avenue felt unsafe to cross, and I did not feel as connected there as I did to Rogers Park or Uptown, where we originally lived when we could afford the rent. On my way to school on the Red Line, I would pass through many diverse neighborhoods and I became familiar with which straphangers got on at which stations.

When I take the Red Line back to my old neighborhood, I still sometimes see the same passengers I saw while taking the train in high school. Now though, people I used to see get off at Uptown stations, specifically Black passengers, now leave at Rogers Park, and people I used to see get off at Rogers Park now take the bus with me going west. I wondered if this was a coincidence or if this is reflective of how the North Side has changed since I left.

The Chicago Sun-Times recently analyzed how between 2010 and 2018, the growing Latino population on the Southwest Side coincided with the displacement of Latino residents from Logan Square and Pilsen. Christian Diaz of the Logan Square Neighborhood Association says that this is because “the most expensive places to live are near public transit and near public amenities like parks or bike lanes.” Compared to Logan Square and Pilsen, the Southwest Side is more auto-oriented and has fewer commercial streets, even after the Orange Line was constructed. “These are neighborhoods that often have poorly funded schools and lack access to any transportation,” Diaz said. “Who [gets] to live in a safe, desirable, and walkable neighborhoods? It’s white people and people with money.”

This made me wonder if a similar reason is why I’ve been noticing Black folks on the North Side moving further north. Chicago’s declining Black population has been discussed in the media for the past couple of years. More than 100,000 Black residents have left the city since 2010. As writer and urban planner Pete Saunders pointed out in the Chicago Reader, “Black Chicagoans aren't flocking to the suburbs so much as leaving the region altogether." I want to know though which specific neighborhoods are losing the most Black residents and if there a few neighborhoods gaining Black residents.

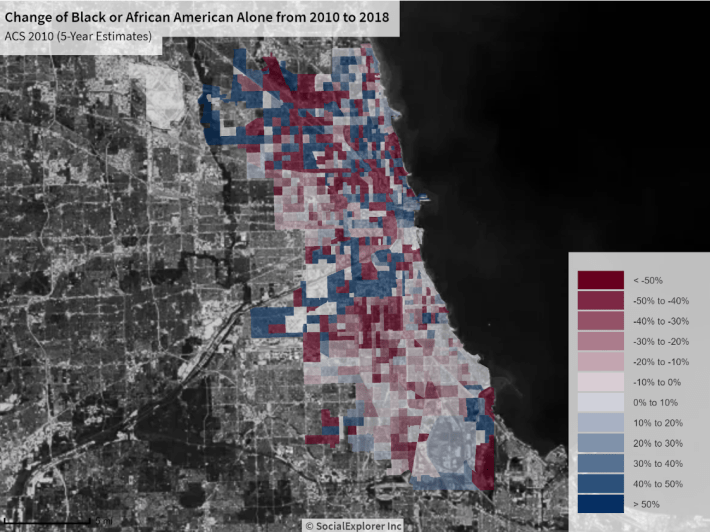

Using data from the recent 2018 American Community Survey, which estimates the U.S. population for that year, I made a map of census tracts showing the change in Chicago’s Black population. Areas in darker red indicate drops in the Black population, while those blue indicate a growing Black population, with a deeper color indicating a larger change.

Many population losses happened along formerly vibrant streets, and corridors that have been significant in Chicago’s Black history and culture. Madison Street has always been the center of life in Garfield Park. 63rd and Halsted in Englewood used to be Chicago's largest commercial center outside of downtown. 79th Street connected many working- and middle-class neighborhoods with miles of businesses. The people here mattered.

Many of these areas would be considered ideal examples of dense transit- and pedestrian-oriented communities. However, the legacy and perpetuation of segregation and disinvestment in Chicago’s Black neighborhoods, through racist housing policies, redlining, and demolition of parts of these communities, is causing many Black folks to leave.

The few neighborhoods that have an increasing Black population are primarily on the North, Northwest, and Southwest Sides, many of which had few Black residents in 2010. (Portions of Jefferson Park and Bridgeport had zero Black folks.) As such, percentages for these tracts are biased towards increases. If we then consider the total number of people instead, we see a starker picture.

Out of Chicago’s 77 community areas, only three grew by at least 1,000 Black residents: West Rogers Park (+2,970), the Loop (+1,278), and Riverdale (+1,169). There were only nine other communities that grew by at least 200 Black residents, such as Morgan Park, Dunning, and the East Side. Of these communities, only Riverdale, Morgan Park, Oakland, and Grand Boulevard are historically Black neighborhoods.

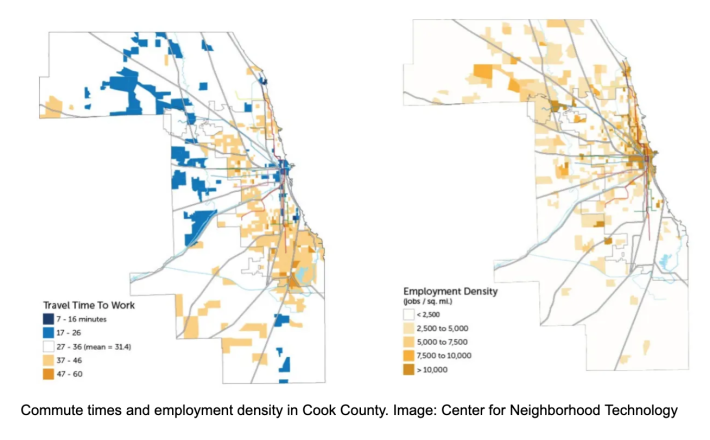

What is also striking is that many of these communities are at the edge of the city, where there are fewer businesses, commercial corridors, and transportation options. Especially in Riverdale, Dunning, and the East Side, traveling to other neighborhoods by transit can take an hour or more, and there is little bike infrastructure. Even Grand Boulevard and Oakland, despite being close to job centers, have longer commute times and had many significant cultural and commercial buildings demolished due to racist urban renewal policies.

The population loss in Black communities is connected to the movement of those communities to the margins of the city. Many of my friends say they no longer feel safe walking on their own block and want to raise their children in a safe and accessible neighborhood. However, many of the neighborhoods that have those qualities are unaffordable, so many of my friends have moved further out in the city, or plan to leave Chicago entirely. Safe streets and good transportation access should be the norm in all Chicago communities, not just majority-white and wealthier neighborhoods.

There are many short-term actions we can take to support population growth in Chicago's Black communities. Plans for bike lanes on the Far South Side and faster bus service on Halsted and Western, to support crosstown travel, should be expedited. The Active Transportation Alliance's Fair Fares campaign for reduced transit fares for lower-income Chicagoans would make transit more affordable for many Black residents, allowing easier access across the city. The south Red Line extension, which still isn't funded, wouldn’t start construction for several years, so Metra should move forward with the South Cook Transit Pilot to provide more frequent and affordable and Metra service on the South Side. Building affordable housing on city-owned land can provide retail space on the ground floors and justify increased transit investments in those communities.

There also need to be longer-term visions that will comprehensively support Black folks and Black neighborhoods across the entire city. The city’s INVEST South/West program is intended support many historically Black neighborhoods that have strong transit connectivity. In addition to supporting our neighborhoods, Black residents must be given the resources we’ve been denied support ourselves. The Metropolitan Planning Council released a report titled The Cost of Segregation which measured the impacts segregation has had on Black and Latino residents, and lists a roadmap to address the harm. This can only be done when the city recognizes disinvestment in these neighborhoods as a public health and safety issue, and as an act of injustice.