In July 2018, the CTA unveiled its All Stations Accessibility Program (ASAP), which outlines a plan for making Chicago transit 100-percent Americans With Disabilities Act compliant by 2038. At the time of the program launch, about 70 percent of the system’s 145 rail stations were accessible, leaving 42 remaining stations to be upgraded within the next two decades. The total cost is estimated to be $2.1 billion over four phases. Given the political realities of how this project will be funded, this schedule is reasonable, according to Adam Ballard, housing and transportation policy analyst at the Chicago based disability rights group Access Living. “Of course, I would like to see it done sooner,” he said. “Twenty years is a long time. But I’ve gotten to know how the funding sources work well enough to know that there’s only so much the CTA can do, and they’ll need a lot of help from the state and especially the federal government to get this job done.”

However, Ballard feels that certain portions of the system should be addressed earlier than what the plan lays out. “The Oak Park area is almost completely unserved by any accessible stations aside from Harlem and Lake,” he said. “The Austin Green Line station is next up so that will change things a little bit, but every other station in the area is still without an elevator. If I was in charge of the prioritization, I would have moved that up. I don’t even live in Oak Park, but access across the West Side and into Oak Park is important.” ASAP has scheduled the Oak Park Green Line station for Phase Three and Ridgeland for Phase Four.

Ballard also notes that most of ASAP’s missed opportunities involve the Blue Line. “The O’Hare branch still has long stretches without accessibility and some of those stations are pushed back until later in the plan,” he says. “I understand their rationale for putting certain stations in different tiers. They’re trying to do stations that are readily achievable first -- ones that won’t take as much work and that seem to have either higher ridership or more connections to bus or other train lines -- so that’s the criteria I would use, but there are some areas of the city that I would like to see addressed a little quicker.”

And while several Red Line stations on the North Side are in the works as part of the $2.1 billion first phase of the CTA's Red and Purple Modernization Program, the Harrison stop won’t be accessible until Phase Four of ASAP. “I think that downtown stations are important, but again underground stations are going to be a lot more expensive so I understand why they emphasized things that are more readily achievable,” Ballard said.

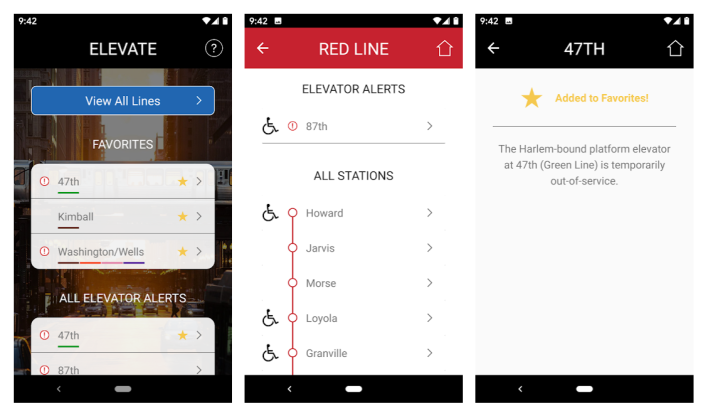

In the meantime, transit riders with disabilities can use the new Elevate Chicago app developed by Loyola students that sends push notifications about elevator outages throughout the train system. Currently only available for Android phones, Elevate Chicago allows users to favorite specific stations and track elevator status in real time. “I helped with beta testing over the summer, and it’s a really good app,” Ballard says.

Another issue that people who use wheelchairs and other mobility devices often face in Chicago are broken sidewalks, missing curb cuts, and other barriers in the built environment. “I think it’s another case where we’d like to see more done, but a lot of it comes down to resources,” Ballard said. “We meet with CDOT at least a handful of times a year to check in on the progress of sidewalk repair and either putting in or replacing curb ramps so I think there’s definitely a concern within the city to get it right. But again there’s only so much money in the budget every year so they have to prioritize certain projects over others.” An app called Chi Safe Path, which aims to provide information about hazards on public walkways and offer alternative routes, has been in the works for a few years but is still under development. Read more about that project here.

Along those lines, Access Living recently worked with the Metropolitan Planning Council on the recently released "Toward Universal Mobility" report, featuring strategies to make the Chicagoland transportation network accessible for all. “Universal mobility is this idea of how to use all the various modes of transportation to provide a pretty seamless and equitable transportation system that works for people with disabilities like it does for everybody else,” Ballard explained. “It also includes walkability or 'rollability' and making sure that sidewalks and curb cuts are accessible and kept in good repair.”

In an effort to better accommodate wheelchair users who travel via Lyft or Uber, the Chicago’s new ride-hail tax structure, which kicked in last week and raised the city fees on most private Uber and Lyft trips, lowered the total tax on trips their trips from the previous $0.72 to $0.65. However, this reduced cost doesn’t apply to those with “invisible” disabilities. “People who are blind or deaf are getting hit with higher taxes and that’s still a hardship for them,” Ballard says. “We appreciate the overall goal of trying to reduce congestion downtown, but we want to make sure that it doesn’t hurt anybody, and right now it’s being applied unevenly because only riders with obvious disabilities are getting the benefit.”

Ballard noted that the growth of ride-hail services not only cuts into ridership for traditional transit, but it also has a direct affect on paratransit. “As mass transit shrinks, so does paratransit coverage, because where ADA paratransit goes is dependent on whether there are fixed routes in an area or not,” he says. “We’re already seeing lost routes -- not so much in the city yet, but in the suburbs -- which means that people aren’t able to sign up for paratransit either. These people can’t use mass transit in the first place and paratransit is their lifeline. So losing mass transit isn’t just bad for the environment and pollution and congestion, but it’s also bad for people with disabilities because the service they receive is entirely tied to the existence of buses and trains.”