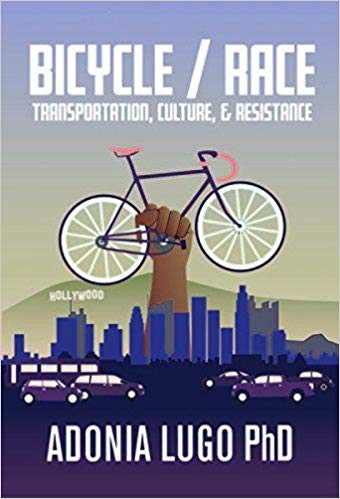

On Thursday, Dr. Adonia Lugo, an LA-based urban anthropologist and mobility justice strategist, gave a talk at IIT about the principles of mobility justice and her new book "Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, & Resistance." Co-sponsoring organizations included Muse Community + Design, Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, Slow Roll Chicago, Go Bronzeville, Equiticity, Active Transportation Alliance, and Streetsblog Chicago.

Lugo started her presentation with the important question, “What makes streets safe or unsafe?” This is a critical question, because the way we answer illuminates the various ways different people experience the public way. She gave the example of how, for an undocumented immigrant navigating the streets of Southern California, safety might mean avoiding police officers, and maybe not getting on a bike.

Lugo compared the transit justice movement, including groups like LA’s Bus Riders Union, and the bicycle advocacy movement. “In the bike movement, there’s a big focus on roads.” She said that in the transit justice movement, there’s more of a focus on people, which makes a difference with what the advocacy looks like. She calls the personal relations that help keep communities strong “human infrastructure.”

She discussed working at the League for American Bicyclists and the barriers she faced there. “I came to be frustrated working in bike advocacy trying to bring up safety issues beyond the roads.” This brought us back to the earlier question of what makes streets safe or unsafe.

“When someone moves through a space, you are going to feel a certain way depending on who you are,” she says. “The problem of driving while Black is the same problems as biking while Black.”

Lugo discussed the conversations that began at the first Untokening convening, which is a multiracial collective that centers the lived experiences of marginalized communities to address mobility justice and equity. The first gathering was held in Atlanta in 2016. Out of conversations there, the principles for mobility justice were developed. Lugo emphasizes the importance of developing new language for our experiences.

“There’s a lot of things important to community members’ lives that we don’t have a vocabulary for in the transportation world,” she said. “To work for mobility justice, you have to make the lived experiences of people a priority.”

After Lugo’s presentation, José Acosta of LVEJO offered remarks before introducing the next part of the program, a panel discussion with Lugo, Dan Black from Slow Roll, and Streetsblog’s own Lynda Lopez, moderated by Romina Castillo from Muse. Acosta emphasized the importance of acknowledging underlying issues in communities before imposing bike lanes or other transportation-related infrastructure. For example, there’s interest in creating bike and pedestrian paths along the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal in Little Village, but the neighborhood has terrible air quality due to industry, so some residents might question why it makes sense to encourage people to ride bikes there.

Castillo began the discussion by asking how residents can best leverage human infrastructure to shift political power. “We need to focus on the people who live in a community, rather than what we’re building there,” Lopez responded. She noted that residents of communities of color may be suspicious when the city wants to bring infrastructure like bike lanes and Divvy stations to the neighborhood, wondering if the amenities are intended for their benefit, or for more affluent newcomers.

Black, who has worked for both the Divvy bike-share system and JUMP, a dockless bike-share company, said that local residents and community organizations were crucial for helping to get the word out about opportunities like the Divvy for Everyone discounted membership program. “We need to do more in Chicago to make sure that kind of ‘soft infrastructure’ is strengthened and broadened,” he said. “We shouldn't allow people that care about helping their communities to have to leave that work. We need to get a budget for them.” He cited audience member Deloris Lucas of the Far South cycling group We Keep You Rollin’ as a great example of a resident who is using bikes for community development.

“Human infrastructure is the stuff that’s there in the community before the development happens,” Lugo said. “People know how to get things done [in under-resourced communities], but we don’t take advantage of that.” She cited Slow Roll Chicago as a great example of human infrastructure that brings people together via bikes. “So you all have that figured out.”

The panel discussed the planned citywide expansion of the Divvy system via a contract amendment with Lyft, the concessionaire. Lopez, who lives in Little Village and has worked in Brighton Park, outside of the Divvy zone, said a friend of hers has referred to the cycles as “gentrification bikes.” “Even if the system is expanded to new neighborhoods like Brighton Park, there’s the question of who would use them,” Lopez said. "Even with the discount, the roads aren’t bike-friendly there.”

“For me it’s about not being so quick to build, but slowing down and listening to what people want in their neighborhoods,” Lopez added. “Maybe it’s more lights.” She noted that street lighting is often subpar on the Southwest Side.

Castillo asked the panelists what they would recommend to the incoming Lori Lightfoot administration in terms of priorities for mobility justice. Lopez said she’d want to make sure that community groups, social justice, and environmental groups are at the table in making decisions about transportation.

Black said he’d like to see Chicago bring back the Department of Environment, which was eliminated under Rahm Emanuel, as well as creating a dedicated fund for mobility education and community engagement.

Deloris Lucas asked the panelists about ways to get residents from across the city to work together in a concerted effort. Lugo responded that the LA area is so spread-out and vast that it can be difficult for mobility advocates from different areas to meet up, so they often communicate via video conferencing or conference calls.

Lopez cited the recent BLK Panel, a summit for African-American cyclists at Blackstone Bicycle Works, as an example of advocates from different facets of cycling and parts of town getting together to brainstorm.

In response to another audience member about the increasing popularity of electric bikes and scooters, Lugo said, “In LA we have a whole micro-mobility ecosystem,” but added that while mobility solutions like these may have some benefits for a city, they might not work in every neighborhood.

Another attendee said he had doubts about the upcoming Lyft/Divvy expansion deal, which JUMP and its parent company Uber have been lobbying against because it would exclude other bike-share companies from operating in Chicago. “It sounds like the parking deal,” he said, referring to the city’s hated 75-year meter contract.

Black responded that Chicagoans should try to educate themselves about the deal, and hold the city accountable for making sure Lyft holds up its end of the bargain and operates the system in an equitable way.