Electric Scooters may not be faster than cars -- or even bicycles -- but they can provide an important “first-and-last-mile” link to public transit routes and bike-share docking stations, expanding access to job opportunities in the process.

Those were the major takeaways from the recently released study "E-scooter Scenarios: Evaluating the Potential Mobility Benefits of Shared Dockless Scooters in Chicago," conducted by DePaul University's Chaddick Institute. The report was bankrolled by Bird, a Santa Monica-based scooter company that lobbied in Springfield this year for legislation that would have allowed people to ride scooters on sidewalks as well as bikeways.

Earlier this month C. Scott Smith, one the study co-authors, gave a presentation about the study and asked attendees to share their thoughts on scooters. Some of the major concerns that came up were whether riders would be allowed to use scooters on sidewalks or whether they would have to stick to roads, as well as how the scooters would be parked, and whether they would be usable by people with disabilities. Chicago Department of Transportation staffers present said CDOT is researching regulatory issues, with a stakeholder meeting expected to be held sometime in January.

The study looked at three study areas representing three sides of Chicago. the North Side study area included the Avondale, Logan Square, North Center, Lakeview, and Lincoln Park community areas. The West Side study area includes the West and East Garfield Park, North Lawndale, and Near West Side community areas. The South Side study area – the largest of the three in terms of size – included the Douglas, Grand Boulevard, Fuller Park, Oakland, Kenwood, Washington Park, Hyde Park and Woodlawn community areas.

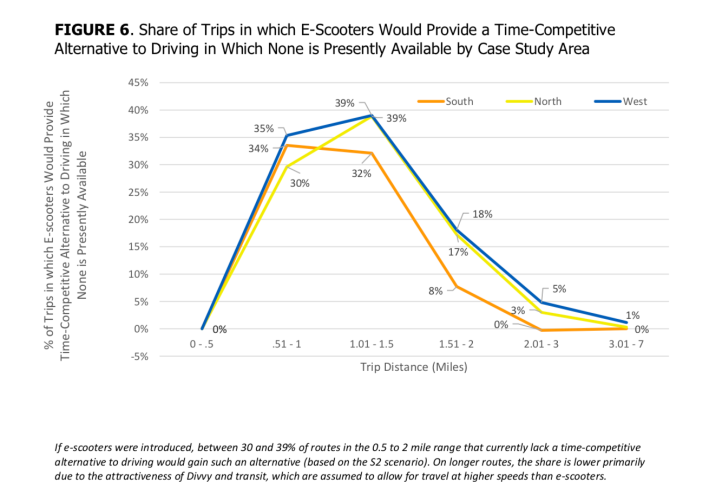

As the study explains, e-scooters' biggest advantage would be that they don't have to be docked and they're space efficient. On other hand, they typically don't travel as fast as bikes, cars, and trains. That's why the study suggests that they would work best for short-distance trips of a half mile to two miles, allowing riders to get to train stations and bus stops. This is especially true in the North Side study area, where car parking is more scarce than in the South and West side study areas. At the same time, because many neighborhoods in the South and West side study areas have fewer transit options, having scooters there would be especially useful for improving transit access.

The study also delved into how cost-effective scooters are. The researchers calculated that, when the costs of parking, insurance premiums and “other costs of having a car in a congested environment” are taken into account, the cost of driving a car you own is $2 per mile, if not more. Meanwhile, it calculated that using an e-scooter would cost between $1.47 and $2.06 per mile, depending on the speed and distance. And it determined that using ride-sharing services costs more per mile over short distances than long ones, “typically in the $4 -$9 per mile range.” So, for those who don't own cars, scooters could be a more cost-effective short-distance travel option.

“This analysis suggests that e-scooters, by offering time-competitive trips at rates per-mile-traveled at or below those of car ownership, could augment a car-free lifestyle that blends transit, carsharing, ridesharing, and Divvy,” the study stated. “Conversely, if a resident already owns a car and avoids significant parking costs, e-scooters could still provide an added value of a more hassle-free manner of arriving at their destination.”

The study went on to look into how this would affect other modes of public transit. Since, as noted previously, scooters are less useful for longer trips, the study estimates that they wouldn't hurt ridership for longer bus and train routes, as well as longer Divvy trips.

In addition the study argued that providing that last-mile link can go a long way toward improving access to jobs, especially in the Loop. It estimated that scooters would “increase access to about 16 percent more jobs within 30 minutes in the Loop business district compared to those accessible by public transit and walking.” This would especially benefit the South Side study area, where the e-scooters would increase access by 37 percent.

Alan Mellis, a long-time Lincoln Park community activist, said that he had two major questions – where e-scooters users would be allowed to ride and whether they would be able to accommodate the needs of people with disabilities.

Regarding the first question, David Smith, a project manager for CDOT's bike and pedestrian program, said that different cities regulate where e-scooters can go differently, and that this was something his department is looking into.

Ranjan Prabhakar from Mayor Rahm Emanuel's office said the city has looked into the second issue as well. “The city actually conducted an engagement sessions with vendors on scooters, and Mayor’s Office on People with Disabilities have spoken about accessibility uses.” One idea that has been bandied about, Prabhakar said, was three-wheeled e-scooters.

Steve Rudolph, manager of air transport policy at Chaddick, noted that, in Chicago, there was a relatively brief period in the 1980s when mopeds were very popular. He wondered how they were regulated, if they were regulated at all, suggesting that if there had been regulations, they could be used as jumping-off point for discussion of e-scooter regulations.

Another major issue that came up was where the scooters would be parked. Several attendees expressed concerns that they would clutter parking spaces and sidewalks. Mellis proposed only allowing them to be dropped off within 5-8 feet of bicycle parking.

John Burns suggested specialized e-scooter racks. “I would treat it parallel to bike parking, because it’s a one-person vehicle,” Burns said. “And I think it would be easier for scooter company [to] design that kind of rack.” he added that he was concerned that simply letting people drop scooters wherever they want would affect the “public aesthetic.” And he suggested another possibility. “I live in La Grange. They’re installing a new – I’d call it a bike shed. Many people commute to train station and leave their bikes all day.”

C. Scott Smith said that Chaddick institute will continue to research e-scooter usage and polities. The city and local transportation advocacy organizations are continuing to study how to manage and regulate the technology. Prabhakar said that the city will be holding “stakeholder engagement session, likely sometime in January.” Active Transportation Alliance is doing its own survey on the subject.

David Smith said that, whether e-scooter ride-sharing turns out to be viable in the long run, it’s a phenomenon worth studying. “I don’t know if scooters are going to stick around on long run, but if it’s not scooters, it’s going to be something else,” he said. “It’s good that we provide alternatives to driving.”