“I knew where I was,” muses Slimm, the 25-year-old road captain from the Los Ryderz Bike Club regarding his fateful decision to roll past 65th on Broadway – the heart of East Coast Crips territory, “but I was just riding by…”

Keeping track of whose territory you are in is key to survival for many young men growing up in South Central.

The area’s oldest gangs are rooted in a self-help spirit – pushing back against violent white incursions into their neighborhoods while instilling pride and a sense of ownership in young black men during a period in which they were aggressively denied so much. But the cumulative legacies of segregation, disinvestment, denial of opportunity, mass incarceration, and repressive policing since pushed them down a more destructive path.

While gangs still offer young men (and sometimes women) validation, a surrogate family, respect, a sense of belonging, a support system, a sense of security, and even a source of income for some, they also exact a high toll on communities.

The contested nature of public space limits everyone’s mobility.

Fear of getting caught in the crossfire or being mistaken for someone else can keep many from lingering outside in the open, even at playgrounds, or walking or biking around the neighborhood, to work, or to school.

Several people have been shot while biking over the last year, including a man in Lincoln Heights, a man near 41st and Main, two men riding near the Indiana Metro stop in Boyle Heights, a man and two women on 77th St. in Florence-Firestone, 39-year-old Jamel Lewis in Pico-Union just two weeks ago, and 17-year-old Jonathan Salas.

Salas, a beloved young man who was part of the police cadet program, was riding home from the dentist at 11:30 in the morning near Hooper and 92nd Street when he got caught in between two people who were involved in an altercation and a third party that had pulled up to fire at them.

More recently, youth just chilling in their neighborhoods have also been felled by bullets, including a girl sitting with her mother in a car just a block from where Salas was killed and 15-year-old Hannah Bell, cut down the other night while standing with her mother outside a popular burger stand at 78th and Western. Bell was killed just a block from where 21-year-old Justin Holmes had been executed while walking with friends last October – a story that only seemed to catch the city’s attention because the driver of the getaway car was a wealthy white teen from Palos Verdes.

The trauma of lost schoolmates, friends, and family members weighs heavily on entire neighborhoods. Not just because of the oppressiveness of the losses or the fear they instill, but also because of the way that their sheer numbers confirm what the community already knew all too well: that society does not value the lives of black and brown youth.

Young men feel this most acutely.

They often can’t move through their own streets without being checked, intimidated, or harassed by gang members and police alike, regardless of their affiliation. They may have to take circuitous routes to avoid particular corners. Local markets may be rendered off limits. Those who are trying to stay straight may have to change up their routes daily – including things like never waiting at the same bus stop twice in a row or getting a car – so they aren’t caught slipping.

Joining up is one way youth deal with the challenge of navigating contested public spaces – it’s easier to move through the streets knowing that homies will have your back. But most soon find that the more “work” they put in and the more they become known, the more likely it is that they will be targeted, meaning there are even fewer places they can go.

This was an ever-present concern for Slimm.

He had decided to stop banging after his last stint in jail. He’d been in and out of jail since he was 15, and just before he turned 18, he found himself looking down the barrel of an eight year sentence – juvenile life. An appeal got him out after three, and he was determined to turn things around.

But the streets never forget.

As he rolled past 65th Street, a guy from East Coast that he had done time with looked up from his phone and did a double-take, calling out, “Hey, hey, I know you, huh?”

“I knew who the dude was,” he says, “so I was like, ‘Nah, bro…I don’t know you.'”

Too late.

Two of the guy’s homies tumbled out of the house. All three piled into a car, and the chase was on.

Slimm says he rode to the burger stand at Gage and Broadway, leaned his bike up against the wall, and awaited his fate.

He wanted it to happen the right way, though. “I know y’all not about to jump me,” he said, offering to fight them one-on-one.

They weren’t about fairness. One took his bike. Another had a gun tucked into his sweater. “So, we got into it,” he says.

Next thing he knew, he was running up the middle of a busy Broadway at rush hour in the rain. They chased him all the way to Slauson – six long blocks north – before a girl he managed to call picked him up.

“After that day I put it in my head like, OK, I can’t go everywhere that I thought I could go,” he said. “And from that day forward, I limited myself. If I don’t feel comfortable or I know I can’t go in that area, I have no problem telling whoever I’m with, ‘Hey I can’t go in that area.'”

It comes up more often than you might expect.

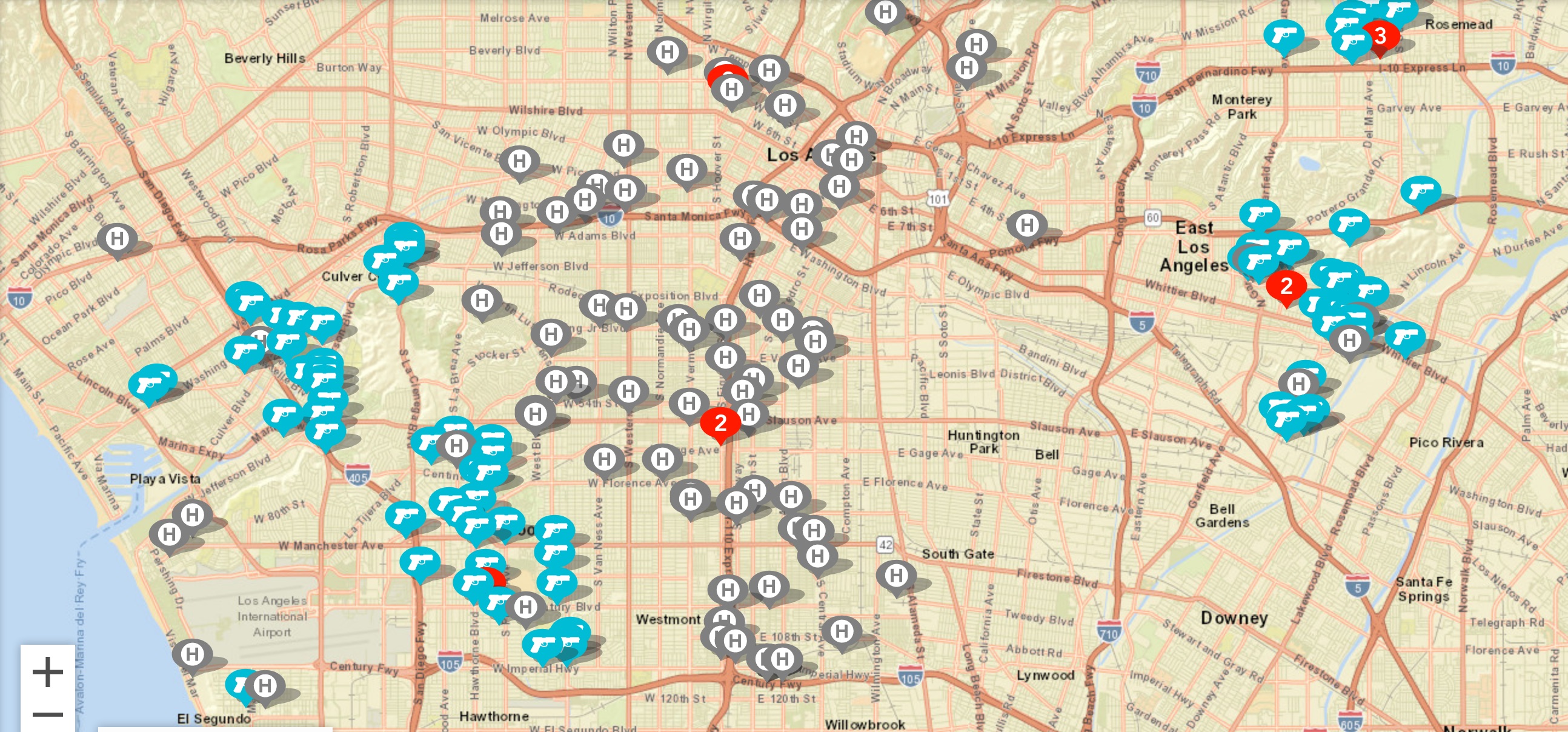

[The map above represents the piecing together of territories held by black gangs by gang researcher Alex Alonso. A partial map of Latino gangs is found here. Click on a territory to learn more about the sets within each of the territories. Please note: a) living within a territory does not equal affiliation and b) affiliation runs on a spectrum.]

Slimm loves to ride, though.

And his enthusiasm, quick smile, and commitment to community have made him well-loved in the cycling community in South Central. He’s also in high demand from other area clubs because of his skills as a road captain who takes the safety of group rides seriously. Which means he’s often rolling through former rivals’ territory. Being part of an organized ride on bikes insulates him somewhat – it’s part of the appeal of the Los Ryderz club for many of the Watts youth who would not otherwise be able to move through certain areas – but he says he still feels uneasy.

When he had to stop and block the intersection of Broadway and Gage while road captaining for a Lady Riders’ ride, he watched his back the whole time.

“I felt a little safer because I was with the bikes,” he says.

And because he had his club vest on – something he hadn’t been wearing the day he was assaulted.

He wears it almost everywhere.

“I still gotta worry about the streets,” he says of wearing the vest. But because it signals to gang bangers that he’s not about that life, it acts as a kind of hall pass. It also lessens the likelihood that he’ll be mistaken for someone else.

“When I have my vest on, I feel safe.”

It also provides a buffer against police harassment.

Normally when he walks, he says, cops look hard at him.

“They try to intimidate you. They look at you and they expect you to turn your head and look down or something.”

It is something that he feels is profoundly unfair – these are his streets, too.

An aunt that helped him learn about his rights gave him the confidence to not accept that state of affairs.

“Because I know I’m not on probation, I’m not on parole – I’m on gang file but I’m not on gang injunction – I look at them back. You mad-dog me, I’m gonna mad-dog you right back,” he says of exchanging looks with the police. “I’m not scared of you. You can’t just pull me over and mess with me because I’m not doing anything wrong.”

When he got stopped while walking down the street one day and they asked to search his backpack, he says he calmly told them, “No.”

“Am I being [put] under arrest? Do you have probable cause to stop me?” he asked. When they replied in the negative, he said, “Have a nice day officer” and went on his way.

“They was mad because it’s rare that a young black person knows the law,” he says with a smile.

“They get mad,” he says again, this time with resolve, “but they can’t just do that.”

When he’s got the vest on, they might not even bother to stop him in the first place.

There’s “a different atmosphere from me having my vest on and riding my bike to me walking down the street without my vest or my bike. It’s a big difference,” he says. “Big difference.”

“Police look at me and keep going.”

He doesn’t mind wearing it – he’s proud of his club and proud to represent it.

But the fact that he has to wear it at all in order to be seen as anything other than a “threat” or a “criminal” speaks to how deeply these barriers to mobility are embedded in the segregationist foundations of this city.

Despite the fact that so many in L.A.’s disenfranchised cores must navigate similar contexts on the daily, it’s still rare to hear the full scope of these issues raised in discussions around mobility. Instead, planners and advocates tend to assume that access to the streets is a given, freeing them to focus on decontextualized barriers to safety like infrastructure and traffic.

Even recent efforts to get Angelenos to care about street safety and Vision Zero (the effort to lower traffic deaths to zero) by city officials and advocates alike have reified that hierarchy by repeatedly pointing out that there are more traffic deaths than gun deaths.

Technically, it’s a true statement. There were 244 traffic deaths in 2017 and 239 gun homicides.

But it’s a troubling juxtaposition.

For one, it’s counterproductive. To put that argument in a Vision Zero framework (as I did in a twitter conversation with Vision Zero L.A. found here), if fear of gun violence means folks can’t be out in their yards, visit their local parks, walk to nearby amenities, jog around their neighborhoods, wait at bus stops, be out after certain hours, or go down certain streets, they’re going to drive more and walk and bike less, compounding the very traffic problems that planners and advocates are trying to curtail.

More importantly, such a comparison obscures and minimizes the extent to which gun deaths and the conditions that facilitate gun violence are both concentrated in particular communities and can paralyze and traumatize them across generations, limiting far more than an individual’s physical mobility. This is especially true for black youth.

For Slimm, what this translates into is a fear of fully evolving into the human being he knows he could be.

“What I’m mainly scared to do is change 100 percent,” he says of trying to walk away from being hyper-aware of ways he is seen or being talked about, defensive, or even aggressive when the situation calls for it. As someone who continues to stay in his ‘hood, he knows that, at present, he doesn’t have the luxury of ever letting his guard completely down. “I changed. I’m changing still. But what I’m mainly scared to do is change 100 percent.”

“I say that because there’s been a lot of people – ex gang-bangers – that did whatever they did. Soon as they have a kid and really start changing their life,” he muses, “they get killed.”

A new father himself, he says, “That’s been my fear…that if I [change] 100 percent, I’ll get killed.”

“Everybody that have a messed up life. Everybody that change they life, that have kids – they get killed. Every single person. This killing around here is getting close to home. It’s starting to be in areas where I ride. The shit’s crazy. They’re not asking no questions no more. They just shoot.”

One only need follow him on social media to get a sense of how pressing an issue this is for him. Every time he hears of an incident in the area, he posts it on facebook – a kid that got shot when the car he was in got caught in the crossfire, a shooting at a nearby fast food joint he’s visited, a homie that got dropped, even his own recent brush with flying bullets while waiting at a bus stop.

Like many at-risk youth from the area, he hadn’t necessarily thought ahead because he didn’t know that he’d make it to his mid-twenties. Now that he has and has a baby boy, a new job, a bike family that makes him feel good about himself, and a chance at a real future to boot, mortality weighs heavily on him.

“You can’t even ride down the street no more. It’s not even [about] being a target. You gotta worry about innocent bullets, ‘Man, was this meant for me?'”

“There’s a whole lot you got to look at,” he says of what goes through his head every time he heads out the door. “A whole lot.”

Many, many thanks to Slimm for sharing his story. A follow-up piece looking at Slimm’s club, Los Ryderz, will offer a window into what it takes to truly “reclaim” streets for youth in communities like South Central. That will drop in a few weeks. In the meanwhile, see some of our past coverage of Los Ryderz here, here, here, here, here, and here. A partial list of other stories on the intersection of disenfranchisement, repressive policing, gang violence, and mobility can be found below:

The impact of trauma:

How violence in a community shapes youth behavior

- “Invest in Us!” say South L.A. Youth in Response to Questions about How to Curb Violence at Town Hall with Garcetti

- It’s a Small World: How Gang Activity Impacts the Livability of Streets (part 1); Are You Ready to Rumble?: Street Fights Take More Violent Turns (part 2); Listening to the Streets in Order to Make Them More Livable: Part III in a Series (part 3)

- South Central Youth Assess Stasis and Change 25 years after the 1992 Unrest

Racial Profiling

- A Tale of Two Communities: New Security Measures at USC Intensify Profiling of Lower-Income Youth of Color (part 1); A Tale of Two Communities, Part II: LAPD Finds it Stirred Up Hornets’ Nest by Profiling USC Students of Color (part 2)

- Gardena PD Ticket, Harass United Riders of South Los Angeles for Taking Lane while the Case of the Hit-and-Run Victim They Were Honoring Remains Unsolved

- “You Don’t Belong Here:” Sheriffs Profile Reporter

- Are You Supposed to be Here?: Officer Harasses Black Cyclists during MLK Day Parade

- Filed Under: Ugly Things You Find on the Interwebs (an FB page claiming black people steal bikes)

- Days of Dialogue Opens Conversation on Police-Community Relations in South L.A., Gets an Earful

- Family of Man Crushed by Train During Altercation with Police over Fare Seeks Answers, Justice

Incorporating these issues into planning processes

- Webinar on Policing and Mobility Underscores Struggle of Urban Planning to Center Justice (2018)

- Equity 101: Bikes v. Bodies on Bikes (2016)

- Man is Shot and Killed by the Officers He Called to Help Search for Stolen Bike. Is it a Livable Streets Issue? (2015)

- Election Reflections: “Law-and-Order,” the Resilience of White Supremacy, and You (2016)

- A Case for the Incorporation of Questions of Access Into Planning for Complete Streets (2013)