Last March the Chicago Tribune’s Mary Wisniewski uncovered a massive discrepancy in the number of tickets being written to bicyclists in Black neighborhoods compared to other communities, especially majority-white ones. For example, Wisniewski found that over a roughly nine-month period in 2016, police issued 321 citations to people on bikes in the Austin neighborhood. But during the same time frame, a mere five tickets were written in Lincoln Park, even though it has one of the highest levels of biking in the city.

In the wake of the report, community members and bike advocates have said the tickets, mostly written for biking on the sidewalk, appear to be an excuse for stop-and-frisk policing to search for illegal guns and drugs, which would otherwise be unconstitutional. Some of them vowed to fight this inequitable enforcement practice.

However, Wisniewski’s latest look at ticketing numbers, published this morning, suggests that little has changed in the past year – police are still issuing most of the bike tickets in Black communities. She found that in 2017 roughly 56 percent of the bike citations were written in majority-African-American neighborhoods, with only about 24 percent written in Latino communities, and a mere 18 percent issued in majority-white neighborhoods. This is despite the fact that Chicago’s population is split roughly equally between the three demographics, and many of the neighborhoods with the highest bike mode share are majority-white.

These neighborhood percentages percentages are similar to those for tickets written between 2008 and 2016. However, Wisnewski found that that the total number of bike tickets written dropped 14 percent between 2016 and 2017, from 4,158 total tickets to 3,577.

Once again there were some absurdly lopsided ticketing numbers. Last year officers wrote 397 bike citations in North Lawndale while – for the second year in a row – only five citations were issued in Lincoln Park. I encourage you to read Wisniewski’s article for a full breakdown of the data, plus commentary on the numbers from local authorities, advocates, bike shop owners, and community members.

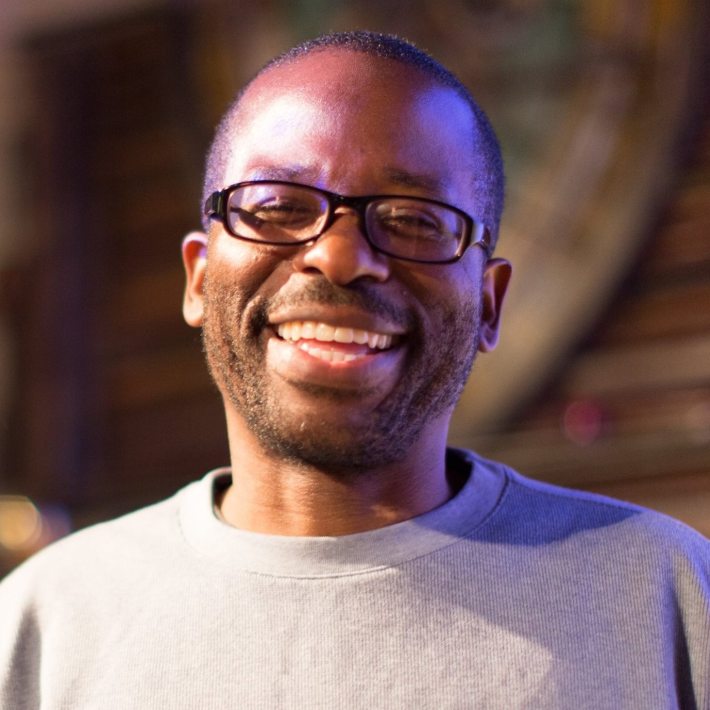

Oboi Reed, the former head of the bike equity group Slow Roll Chicago who currently leads the mobility justice organization Equiticity, is briefly quoted in the Tribune piece, stating that he believes the bike ticketing is an excuse for stop-and-frisk policing. I checked in with him earlier today for his full reaction to the news.

Reed said he “was really quite shocked” by the new numbers, especially because he and other Black advocates met last year with representatives of the mayor’s office and the Chicago Department of Transportation, which is leading the city’s Vision Zero efforts, to discuss the ticketing issue and other Vision Zero-related matters.

Joining Reed at the sessions were Ronnie Matthew Harris, from the transportation advocacy group Go Bronzeville, and public policy consultant Amara Enyia. Representatives for the city included deputy mayor Andrea Zopp, deputy policy director Cara Bader, deputy chief of staff for public engagement Roderick Hawkins, and CDOT commissioner Rebekah Scheinfeld.

The advocates presented the officials with a list of nine “Vision Zero Asks” to make the crash-reduction plan more equitable. For example, they requested that additional traffic policing be taken off the table as a Vision Zero strategy in light of the Chicago Police Department’s documented issues with civil rights abuses. They also asked that the leadership of the Vision Zero program be transferred to one community organization on the South Side and one on the West Side, since the city is focusing its efforts on high crash neighborhoods in these parts of town. Reed said that, disappointingly, the officials tuned down both of these requests, although they committed to creating more ownership of the program on the local level, which he said was encouraging.

At last year’s meetings, the advocates also brought up the bike ticketing issue. “The mayor’s office said they were taken off guard by [the ticketing numbers] and would take steps to change this,” Reed recalled. “But despite their promise, this inequity is still taking place.”

“There will be a full-throated response [from advocates] to the city’s continued racism, inequity, bias, and paternalism, which continues to harm, and in some cases kill, Black, Brown, and Indigenous people of color in our city,” Reed added. “These tickets are financially harmful, and socially harmful, and any police interaction in our neighborhoods comes with a risk [of police violence.] We’re bearing the brunt of this policy.”

It’s certainly disheartening that little has changed since Wisniewski’s last report on unfair bike ticketing practices. The city is under intense pressure to address the issue of racially biased policing, and part of the response includes plans for a new $95 million training academy on the West Side. Solving the problem of unfair bike ticketing practices seems like a relatively simple matter – commanders should be able to order their officers to ease up on ticketing in parts of town that are currently getting a disproportionate number of tickets. While it’s possible that more sidewalk riding is occurring in North Lawndale than Lincoln Park, surely it’s not 80 times as prevalent there.

Moreover, the CPD should have expected that if it didn’t change its ticketing practices, it would once again be embarrassed by a news report on the issue. The fact that the force still didn’t bother to take action on this relatively cut-and-dried matter doesn’t bode well for its ability to solve much more complex and challenging police abuse problems.