[Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield publishes a weekly transportation column in the Chicago Reader. We syndicate the column on Streetsblog after it comes out online.]

In November 29, Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced the latest step in his grand scheme to create luxury high-speed express service between downtown and O'Hare. His office had issued what's known as a request for qualifications (RFQ) for concessionaires to plan, finance, construct, and run the route. Emanuel addressed reporters from within the empty shell of the partially completed, roughly $250 million "superstation" his predecessor Richard M. Daley built underneath Block 37, a symbol of that mayor's failure to achieve the same dream.

Emanuel said the multibillion-dollar initiative is crucial for Chicago's future, and argued that fortune favors the bold. "More than a century ago, Daniel Burnham encouraged Chicago to 'make no little plans,' " the mayor said in a statement, adding that the express "will build on Chicago's legacy of innovation and pay dividends for generations to come."

But after reviewing the details from the RFQ, local transit experts aren't so sure. They wonder whether building the route could be practical and profitable for a private company without requiring a subsidy from taxpayers. Tech guru Elon Musk's recent announcement that he will compete for the opportunity to dig a tunnel for whisking passengers to O'Hare in "electric pods" isn't raising their confidence in the project's viability. And transportation advocates question whether the express, geared toward well-heeled travelers and business people on expense accounts, represents an equitable use of city resources.

The new document states that the goal of the project is to cut the time of the Loop- airport trip from the current 40 to 45 minutes via the CTA Blue Line to 20 minutes or less, with service every 15 minutes during most of the day (the el generally runs every four to ten minutes). The express fare is supposed to be cheaper than a cab ride, which the city estimates at around $60, or a ride-share trip, estimated at roughly $40. Chicago aviation chief Ginger Evans has previously projected that an express ticket would cost between $25 and $35 compared to the current fare of $2.25 to O'Hare and $5 from it.

The request for qualifications stipulates that the project must be financed entirely by the concessionaire, but Evans has previously acknowledged that public funds will likely be used for building the stations themselves. RFQ responses are due on January 24, after which the city will select a handful of candidates to move forward with a request for process, the next step in a Hunger Games-like competition to come up with the winning bid.

Created by the engineering firm WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff as part of a $2 million planning contract, the RFQ identifies three potential routes and four potential downtown terminals for the service, although the city remains open to other ideas.

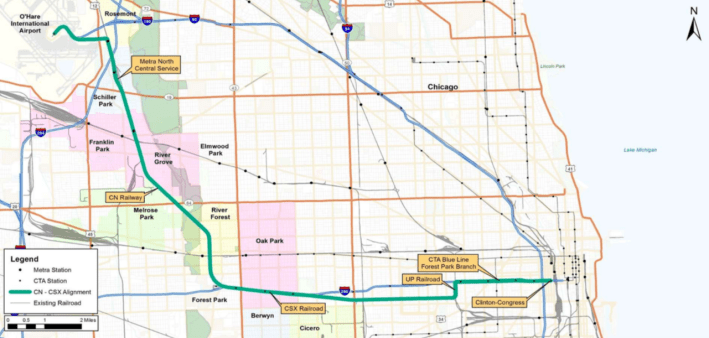

The first route, the CN-CSX Corridor, would run southeast from O'Hare on Canadian National Railway tracks to west-suburban Forest Park, where it would use the Eisenhower Expressway Corridor and CSX tracks to head east to a downtown station at Congress and Canal.

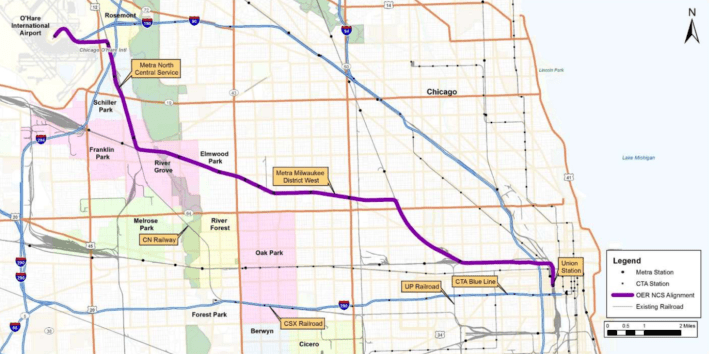

The second option, the NCS Alignment, would use Metra's North Central Service line with either a downtown terminal at Union Station or a new facility southwest of Kinzie and Canal.

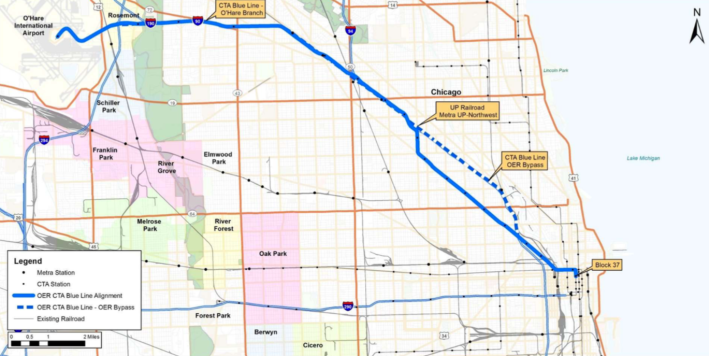

The third route, the CTA Blue Line/Kennedy Expressway/UP-NW Corridor, would parallel the el line in the Kennedy median as it leaves the airport, bypass to the Union Pacific- Northwest Metra tracks north of Belmont (where the Blue Line goes underground and then becomes an elevated route), and meet back up with the el corridor downtown, ending at the Block 37 superstation.

"The initiative will no doubt make many unexpected turns before know we whether or not it is a feasible," says DePaul University transportation expert Joe Schwieterman. "Like many others, I’m skeptical it can be done with strictly private financing, but I also feel the effort could spur a larger discussion about better cross-town connectivity and modernizing our transit system... It faces long odds, but testing the waters could force us out of our comfort zone and produce surprises."

Rick Harnish, director of the Midwest High Speed Rail association, has eagerly endorsed the O'Hare Express in the past. He contends his group's CrossRail proposal, which would connect the North Central Service route to Metra's Electric District line on the southeast side via a freight route along 16th Street, would add value to the project. Harnish says both the CN-CSX and NCS options seem viable, but the Blue Line scenario isn't realistic because it would require building above or tunneling below the el tracks.

That's where Elon Musk comes in. Musk claims his cheekily named Boring Company has proprietary technology that can dig a tunnel 14 times faster than conventional methods, at perhaps a tenth of the cost. In June then-deputy Chicago mayor Steve Koch met with Musk in LA and returned impressed.

After the RFQ was released, Musk tweeted that "The Boring Company will compete to fund, build & operate a high-speed Loop connecting Chicago O'Hare Airport to downtown." (He subsequently clarified that, unlike his much-hyped Hyperloop scheme to shoot vehicles at more than 600 mph between cities, the roughly 20-mile passageway from Block 37 to O'Hare wouldn't require the use of vacuum-sealed tunnels.)

Harnish is highly skeptical of Musk's claims. He notes, for example, that while the inventor plans to save time and money by digging a much narrower tunnel than a typical subway, the Boring Company hasn't addressed the issue of how to evacuate passengers in an emergency.

"I always reserve the right to be proven wrong," Harnish says. "But certainly [Musk's proposal] is a very high-risk endeavor for something that's such a high priority for the mayor."

Center for Neighborhood Technology director Scott Bernstein says he's also "a bit dubious" of Musk's claim of revolutionary digging technology. Moreover, he's doubtful that enough travelers would be willing to shell out big bucks for the premium airport service, which could include nicely upholstered chairs, work tables, and beverage service: "How much luxury do you need in 20 minutes?" But even if the express were to get sufficient use, Bernstein wonders if it would cannibalize Blue Line revenue. "Would they be raiding ridership from one part of the system to support another part?"

The Active Transportation Alliance is concerned about the city's focus on high-end airport service. "Time and attention are being commanded by this project, and these resources could be directed to more efficient and equitable transit solutions," wrote ATA director of government relations Kyle Whitehead in a blog post last month. He argues that Chicago should concentrate on improving transit access from Chicago neighborhoods to jobs and other key destinations.

Oboi Reed, a leader of the mobility justice groups Slow Roll Chicago and Equiticity, agrees that the express plan, as outlined in the RFQ, wouldn't be a wise use of public resources. However, he said he would support a Blue Line-based route that includes improvements to the line's Forest Park branch, which serves lower-income black neighborhoods like Garfield Park, North Lawndale, and Austin.

As for Musk's potential involvement, Reed says he's willing to keep an open mind, adding that it's crucial for residents to have a say in how this tech is delivered to their communities. "Tell Elon to call me, let's talk."