[Streetsblog editor John Greenfield publishes a weekly transportation column in the Chicago Reader. We syndicate the column on Streetsblog Chicago after it comes out online.]

The late 50th Ward alderman Bernard "Berny" Stone was a colorful character, to say the least. Elected in 1973 under Mayor Richard J. Daley, he presided over the far-north-side West Ridge community for nearly four decades. Throughout his career Stone was famous for his feistiness.

In the 1980s he was an original member of the Vrdolyak 29, the nearly all-white aldermanic bloc that tried to thwart Mayor Harold Washington's every move during the racially charged Council Wars. Stone reportedly relished the many verbal battles he got into at City Hall during this period. In 1986, for example, he mocked compact then freshman alderman, now congressman Luis Gutierrez as a "little pipsqueak."

In 1993, angered by plans for a new Evanston shopping center that he argued would lead to more car traffic in his ward, Stone had a nearly three-foot guardrail, nicknamed "Berny's Wall," installed in the center of Howard Street between Kedzie and California Avenues to block drivers from crossing between the suburb and the city. A judge ordered him to remove it the following year.

During his later years in office, Stone sometimes fell asleep during council meetings but was no less fiery. In 2011 he lost an acrimonious runoff election to Debra Silverstein, an ally of Mayor Rahm Emanuel. Stone passed away in December 2014 at age 87.

Earlier this month, Silverstein showed good sportsmanship when she joined Emanuel and members of Stone's family to cut the ribbon on Bernard Stone Park, a memorial to her former foe. Located by the west bank of the North Shore Channel, just south of Devon Avenue, the 1.8-acre green space replaces what was the weed-strewn parking lot of a defunct movie theater.

Silverstein says naming the park after her onetime rival was her suggestion. "Given that he was one of the longest-serving aldermen, I felt like that would be a nice tribute to his service." That's big of her, considering that during the election Stone reportedly dismissed Silverstein, whose husband, Ira, is a state senator, as "nothing but a housewife."

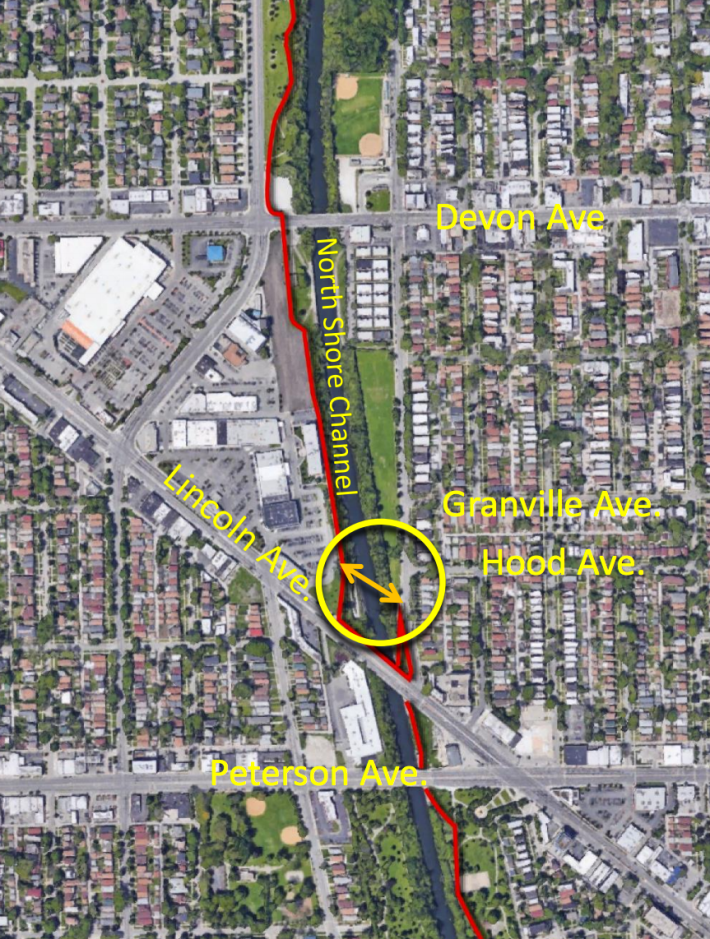

It's also ironic that the park that honors Stone will be served by an upcoming bike-and-pedestrian bridge the alderman put the kibosh on while he was still in office, for reasons that remain somewhat mysterious. More than a decade after the bridge was originally planned, the Chicago Department of Transportation is finally moving forward with building the 180-foot-long weathered steel structure over the channel, just south of the new green space. Construction is slated to begin in early 2018 and wrap up a year later.

Officially called the Lincoln Village Pedestrian Bicycle Bridge, it will provide the final missing link in the North Shore Channel Trail, which runs nearly seven miles from Albany Park to Evanston. Most of the path's Chicago portion hugs the east bank of waterway, but north of Lincoln Avenue the trail shifts to the west bank. As it stands, people strolling, running, and biking are forced to make the crossing via Lincoln or Devon, busy four-lane highways.

By 2005, CDOT had designed a bridge near this location and secured funding for it. But Stone, who'd originally endorsed the project, pulled his support, forcing the department to put the initiative on ice. (I was working as CDOT's bike parking czar at the time but wasn't involved in bikeways planning discussions.)

According to CDOT deputy commissioner Luann Hamilton, who worked on the project back then, Stone claimed his opposition was based on feedback from neighbors east of Kedzie, which parallels the east bank. He said residents were worried about people parking on their streets and using the bridge to access the Lincoln Village Shopping Center, west of the channel. But Hamilton says the alderman provided no documentation to support this claim.

Not long after Stone gave the thumbs-down on the bridge project, the Lincoln Village Senior Apartments were constructed just west of the trail, near the proposed span site. "An alternative theory was that the developers . . . were concerned that the bridge would impact or detract from their site," Hamilton says.

A handful of bike advocates held a meeting with Stone to discuss the matter, according to Bob Kastigar, a retired WTTW technician who lives in the neighboring 39th Ward. "It started out friendly but soon degenerated as it became clear he wasn't going to change his mind," Kastigar says. Stone claimed he was concerned that cyclists coming off the bridge might be struck by drivers in the shopping center parking lot. "But there was a large distance between the path and the parking lot, so that didn't make any sense. We were trying to find out what his [real] concern was."

Former Active Transportation Alliance executive director Rob Sadowsky, now living in Portland, Oregon, claims that, as with the Vrdolyak 29's resistance to Washington, there was a racial element to the bridge opposition. Sadowsky says that while he was working for the Jewish Council on Urban Affairs in 2001 he attended a meeting on affordable housing in the 50th Ward during which Stone referred to African-American and Latino youths as "little blacks and browns." The alderman implied, according to Sadowsky, that the ward should avoid measures that would bring more young people of color to the neighborhood.

Sadowsky adds that when he was leading Active Trans in the mid-2000s, CDOT staffers working on the bridge project indicated that there was racially motivated NIMBY resistance to the span from white homeowners and merchants as well as from Stone. "They believed that nonwhites would travel in hordes through the ward. But no one would say that in public—they would talk about 'gangs.'"

"That infuriates me," responds Stone's daughter Ilana Stone Feketitsch, who served as the alderman's chief of staff during the last 18 years of his career, in response to Sadowsky's statements. "Never did he ever dismiss anyone of any race, color, and creed. He was a great man who lived his life for his community, including people of every race and religion." Asked about her father's involvement in the racially charged anti-Washington resistance, she responds, "He got caught up with what was going on and what he believed in."

Feketitsch, who has lived in Arizona for the last two years but attended the park ribbon-cutting, says her recollection of the bridge issue is spotty. But she says she believes the alderman's main concern was the opposition from the residents east of Kedzie, which she doesn't think was racially motivated. "He always stood for what the community wanted—they came before the bicyclists." Feketitsch adds that she currently supports the project. "It's a good thing that people from other parts of the city will use the bridge."

"That's utter nonsense to say it was a racial issue," echoes Stone's son, Jay, a hypnotherapist who in 2003—contrary to his father's wishes—unsuccessfully ran for 32nd Ward alderman against machine incumbent Ted Matlak. The younger Stone notes that the 50th Ward is home to a wide range of groups, including "Jews, Muslims, Catholics, Indians, Pakistanis, Assyrians, and African-Americans. It's such a melting pot. The biggest thing I was proud of my father for was his ability to bring people of different races and religions together." He adds that, as a cyclist himself, he was in favor of building the bridge back in the mid-2000s, but he respected his father's position on the issue.

In 2007 aldermanic challenger Naisy Dolar used the missing bridge as a campaign issue. Berny Stone blasted that strategy as "ridiculous" before defeating Dolar at the polls.

After Silverstein ousted Stone in 2011, she told CDOT she was interested in resurrecting the project. (She now says that she has no idea why Stone blocked the bridge, and hasn't heard much from constituents on the subject.) But by then the bridge funding had been used for other projects, and a canoe launch had been built at the planned bridge location, forcing the department to return to the drawing board.

In January 2013, the Illinois Department of Transportation allocated $979,600 for the bridge, but it took a few more years until additional federal and local money could be lined up for the $3.4 million project budget.

In September 2016, Silverstein and CDOT officials including Hamilton held a community meeting to present the latest plans for the bridge, which will be located just north of the canoe launch. "When they were finished there was a long period of silence," Kastigar recalls. "There wasn't any opposition. Finally someone started applauding and we all joined in."

Kastigar suggests that we should name the span the Stone Bridge, not to honor the alderman but to serve as a reminder of how one pugnacious politician can derail a worthwhile project for years. "I'm sorry he didn't live long enough to see the bridge get built."