Alma Cruz Zamudio Arias, a woman who dedicated her adult life to fighting for social justice causes, including equitable transportation access, passed away last month at age 26. She was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, immigrated to Joliet with her family when she was four, and recently lived in Pilsen. Alma earned a BA in urban planning and public administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and was a graduate student in the university’s Master of Urban Planning and Policy program. She campaigned for a variety of causes, including mobility justice, affordable housing, early childhood education, and labor rights.

Alma was involved with several Latino social justice organizations, including a campaign by the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization and other groups to improve bus service in Little Village. During her time with Latin United Community Housing Association, she worked on zoning issues for Tierra Linda ("Beautiful Land"), an affordable housing project that will be built on vacant lots in The 606 corridor in an effort to prevent the displacement of longtime residents during the current real estate boom along the trail. Alma was also a member of Somos ("We Are") Logan Square, which has campaigned for higher amounts of affordable housing, at lower rents, to be included as part of new upscale transit-oriented development projects along the Blue Line in Logan Square.

Reflections on Alma’s life from her friend and colleague Streetsblog reporter Lynda Lopez

“I first met Alma in the fall of 2014. She was working as LUCHA’s housing organizer and was canvassing for the Tierra Linda affordable housing complex (which LUCHA hopes will be completed by year’s end). Mutual friends and interests would bring us together a lot more over the next few years.

In 2015 and 2016, I was involved with Grassroots Illinois Action’s efforts to slow down displacement along The 606, such as protesting the development of $900,000 luxury single-family homes near the trail. Alma was involved with Somos Logan Square on various efforts ranging from collecting signatures against the luxury TOD towers rising on Milwaukee Avenue (notably MiCA, the twin tower project across the street from the California Blue Line station), to leading a direct action against a TOD on Armitage Avenue. She was always at the forefront of planning, even when you didn’t see her. Alma was tireless when working for her community. She was always thinking about next steps, always strategizing. Alma was committed to reimagining neighborhoods where housing was a right for all and not just a privilege for a select few who could afford it.

For me, remembering Alma goes far beyond what she did, but what she stood for. Alma was one of the few people I know who was always bringing up how our movements for affordable housing have to be inclusive. At actions, she would make sure those directly affected were the ones speaking. At meetings, she would call out white men who spent more than their fair share of time talking. Alma sought to create a world where community members would be the ones envisioning and creating livable environments for ourselves. This is why she decided to study urban planning at UIC. She wanted to be one more woman of color at the table in spaces where too few of us currently exist.

While Alma may no longer be physically with us, she has left a legacy. I know I will hold the values she upheld close to my heart as I seek to do this work. She served and continues to serve as an example for what urban planning and anti-displacement work can look like. Her mere presence as a planner and advocate has opened up avenues for more women of color. Alma taught us what it means to challenge our work, to critically think about our roles, and to truly center community as we seek to make change.”

Some of Alma’s transportation and housing campaigns and projects

Restoring bus service on 31st Street Since Little Village is a blue-collar Mexican neighborhood—with the highest percentage of residents under 18 of any Chicago community, according to the U.S. Census—it has a high demand for transit service, as do most other local Latino neighborhoods. The 31st Street route had been canceled in 1997 due to low ridership, leaving the #21 Cermak and #60 Blue Island/26th Street buses as the only east-west bus lines serving Little Village.

"So if you lived in southern Little Village you had to walk all the way up to 26th or Cermak," Alma said. "Old people couldn’t walk all that way, and some residents are afraid to walk on certain blocks."

With Alma’s help, LVEJO won a partial victory in summer 2012, when the CTA agreed to extend the existing 35th Street bus line west to include 31st Street between Kedzie and Cicero. Since then, a coalition of other south-side groups successfully lobbied the CTA to test an additional bus line farther east on 31st Street. The pilot launched in fall 2016, and so far ridership is meeting expectations, so it's likely that the service will become permanent.

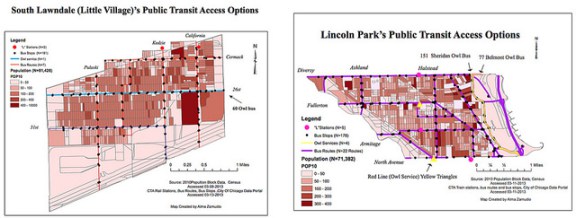

Comparing Transit Access in Lincoln Park to South Lawndale During college Alma compared transit access in the these community areas (the latter largely makes up Little Village) for a presentation at an Illinois African American and Latino Higher Education Alliance conference. She found that while, at the time of her research, 22 bus routes intersected Lincoln Park, only seven served South Lawndale. Lincoln Park had four transit routes with late-night “owl service,” but South Lawndale only had one, the #60 Blue Island/26th bus. And while there are three ‘L’ lines and five stops in Lincoln Park, there’s only one train line and two stations in South Lawndale. Buses and trains also ran more frequently in Lincoln Park.

Meanwhile South Lawndale had a somewhat lower household car ownership rate than Lincoln Park, 84 percent versus 86 percent. When you factor in the fact that South Lawndale had over 10,000 more residents, that comes out to a significantly higher number of car-less households. Moreover, South Lawndale had the highest percentage of residents under 18 of any Chicago community area.

That meant that while the South Side neighborhood had a higher demand for transit access, it received less service, Alma said. “The study proved what I already knew on the ground,” Alma said. “It’s not equitable.”

The demonstration against the TOD at 2501 West Armitage Alma said that blockading upscale TOD construction sites such as this one was a last-resort effort to draw attention to the displacement crisis in the midst of the Logan Square development boom. “We have tried everything,” she said. “We collected signatures against the Twin Towers," she said during the Armitage demonstration in November 2016. "We have had people go to community meetings. [Local alderman Joe Moreno and the developers] aren’t willing to negotiate with us… We are tired of our community being taken from us.”

A memorial fund has been established to raise money for funeral expenses, and any additional funds raised will be used to create a scholarship in her honor. While Alma’s intelligence, energy, and spirit will surely be missed during future campaigns for transportation, housing, and labor justice, it’s clear that her work will continue to inspire other planners, advocates and activists.