[I publish a weekly transportation column in the Chicago Reader. We syndicate the column on Streetsblog Chicago after it comes out online. This particular column is a bit off-topic for Streetsblog, but I thought it would still be of interest to some of our readers.]

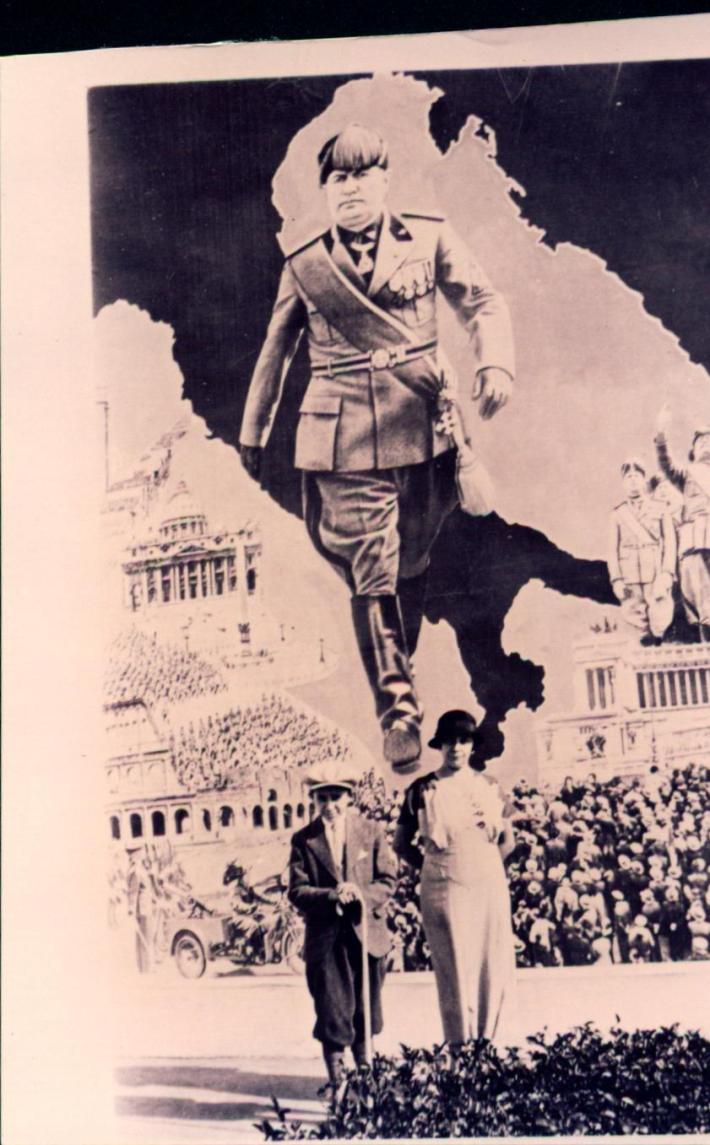

When battle lines were drawn in Charlottesville, standing among the white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and Ku Klux Klan members ("some very fine people," according to President Donald Trump) were men brandishing shields bearing the image of an ax bundled with wooden rods—a symbol of fascism. That weekend's tragic events, which swirled around a "Unite the Right" rally against the city's decision to remove a public Confederate statue, reminded Northwestern University history professor Bill Savage of the disturbing fact that there's a 2,000-year-old Roman pillar on Chicago's lakefront, donated to the city by fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

Ironically, the Balbo Monument stands by the Lakefront Trail near the Soldier Field World War II veterans' memorial. It commemorates the 1933 transatlantic flight by Italo Balbo, a leader of the Blackshirts, the paramilitary wing of Italy's National Fascist Party, who later became Mussolini's air commander and governor of Libya. The aviator led a squadron of 24 seaplanes in formation to our city's Century of Progress World's Fair. An inscription on the pedestal reads, in part:

Fascist Italy, by command of Benito Mussolini

presents to Chicago

exaltation symbol memorial

of the Atlantic Squadron led by Balbo

that with Roman daring, flew across the ocean

in the 11th year

of the Fascist era

Balbo became a hero to Chicago's Italian-American community, and within a year Mayor Edward Kelly changed the name of Seventh Street to Balbo Drive to curry favor with that immigrant constituency.

The day after the August 12 Unite the Right rally, Savage tweeted, "CHICAGO: Time to remove monuments to racism & fascism, 'Balbo Column'; & rename Balbo Drive too." "Every time I bike by that column it irks me," he later told me. "A street in our city center named for a fascist? No."

This wouldn't be the first time Chicagoans have tried to get rid of these tributes. As detailed in a 2008 Chicago magazine piece, shortly after World War II, Chicago alderman John Budlinger led a campaign to rename the street that was backed by veterans, Gold Star families, businessmen, and even the state Parent-Teacher Association, but the legislation died in committee. Proposals to change the street name and/or remove the monument have cropped up every decade or two since that time, and they've been met with stiff opposition from some local Italian-Americans who view the landmarks as vital historic artifacts and sources of ethnic pride.

Aspects of Balbo's biography support Savage's argument. Following World War I Balbo orchestrated vicious Blackshirt attacks on anti-fascists, including, it's suspected, the horrific clubbing murder of opposition priest Don Giovanni Minzoni. Balbo was a key planner of the 1922 "March on Rome" coup that brought the dictator to power. Some historians have said that during Italy's unprovoked invasion of Ethiopia, Balbo's air force dropped bombs and fired machine guns at unarmed citizens (although local apologists for the aviator say that story is a myth). And after the airman was accidentally shot down by his own troops in Libya in 1940, Hitler credited Balbo for his own rise to power in a 1942 speech, noting that "Brownshirts might perhaps not have arisen without the Blackshirt."

Like Nazi artifacts, the fascist pillar belongs in a history museum, not public space, and it's time the drive be renamed. Would the local Italian-American community be on board with removing these tributes to fascists if they were replaced with ones memorializing more worthy figures? Saint Frances Cabrini or University of Chicago physicist Enrico Fermi are worthy candidates who actually lived in Chicago. Cabrini founded a Catholic religious institute with dozens of branches that served the sick and poor, died here in 1917, and was the first naturalized American to be canonized. Fermi, who fled the fascists in 1938, led the creation of the world's first nuclear reactor.

To get reactions to the idea, I contacted the offices of northwest-side Italian-American aldermen Nicholas Sposato, Margaret Laurino, and Anthony Napolitano. I left messages with the downtown aldermen whose wards include Balbo Drive, Brendan Reilly and Sophia King (her district also includes the pillar). I also left a message with southwest-side alderman Ed Burke, who leads the city's Finance Committee, the staff of which creates local history exhibits for City Hall.

The next morning, the Sun-Times's Michael Sneed reported that Burke and northwest-side alderman Gilbert Villegas were calling for "righting a wrong" by removing the Balbo tributes. "I'm amazed the citizens of Chicago have not demanded that these symbols of fascism . . . be removed decades ago," Burke told Sneed. The aldermen said they plan to lobby the Chicago Park District, which owns the column, to remove it, and petition the City Council to rename the street for former mayor Martin Kennelly, who was Irish-American.

Alderman King's spokeswoman Joanna Klonsky provided a joint statement from King and Reilly saying that they too were exploring options for renaming Balbo Drive and removing the monument. "Balbo is a symbol of racial and ethnic supremacy, and in this day and age we need positive symbols," King says in the statement. "It's high time we removed these symbols of oppression and anti-democracy from our city." Reilly added that, since Chicago has been home to "many great Italian-Americans," the aldermen hope to rename the street after a "worthy" one. They say they'll announce plans for the alternative street name in the near future.

A couple of Internet petitions calling on city leaders to remove the Balbo tributes also appeared online recently. Labor organizer Matt Muchowski's campaign, which doesn't propose a new street name, had more than 370 supporters as of August 17. A petition calling for the drive to be renamed in honor of anti-lynching activist, journalist, and suffragist Ida B. Wells, a black Chicagoan, had garnered over 670 signatures by that date.

It's clear that the Balbo abolition movement has legs. Park District spokeswoman Jessica Maxey-Faulkner said officials plan to meet with aldermen soon for "a thoughtful discussion" of the issue. South-side alderman Anthony Beale, who chairs the city's Transportation Committee, told me he's interested in collecting feedback about changing the street name. North-side alderman and gubernatorial hopeful Ameya Pawar has also tweeted support for the removals.

The Italian-American aldermen I spoke to were also generally receptive. "I would be in favor of replacing the [street] name with that of a distinguished Italian or Italian-American," says Laurino, adding that she also supports removing the pillar.

Sposato, whose family immigrated from Italy in the early 1900s, is in favor of taking down the Mussolini-donated column. "Anyone who sided with Hitler was not a friend of America, I'll tell you that," says the alderman, who adds that his great uncle died fighting the Axis powers in World War II. Still, he opposes changing the street name on the grounds that erasing geographic names that honor problematic leaders could be "a slippery slope."

While Sposato acknowledges that the current focus on removing memorials to enemies of the United States, such as Confederate generals, is justified, he points out that there's been discussion of changing the name of Chicago's Washington Park, which was dedicated to the first U.S. president, who was a slaveholder. The park would instead honor the late Mayor Harold Washington. "Where do you draw the line?" (On August 17 Mayor Rahm Emanuel indicated that changing the park's name is a nonstarter, but he also said he's open to exploring Burke and Villegas's proposal.)

Sposato added that, if Balbo Street is going to be renamed, "It's got to be after a famous Italian-American," rather than Kennelly.

Local Italian-American civic leaders, contacted about replacing the Balbo tributes with memorials to Cabrini or Fermi, had mixed responses to the proposal. George Randazzo, founder of the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame, calls it a "no-brainer." "Two great names are being offered, and the monument can go in a museum," he says, "I don't see how anyone loses here." The community should also consider other possible honorees, he adds.

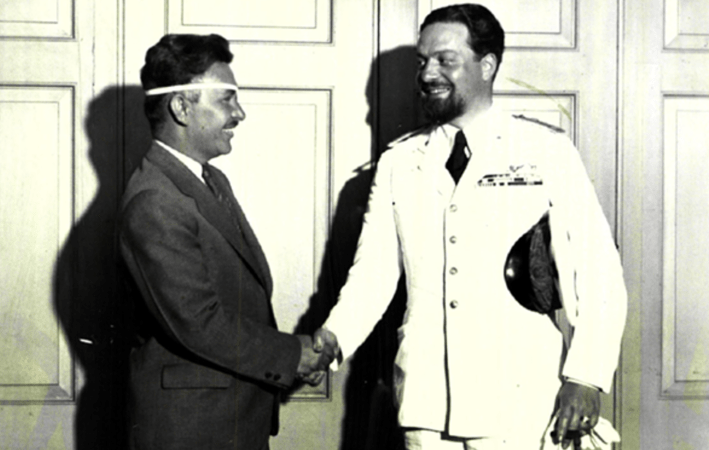

But other longtime advocates for preserving Italian history in Chicago disagree. "Italo Balbo is a hero in our community, and we will fiercely oppose efforts to remove his memorials," says Dominic DiFrisco, president emeritus of the Joint Civic Committee of Italian Americans. Back in 1933, he notes, Italy was considered an ally of the U.S., Balbo dined with Franklin Roosevelt, and his arrival in Chicago was an unprecedented source of pride for Italian immigrants, a scientific achievement that belied stereotypes about Italians being technologically backward.

While DiFrisco makes no apologies for Mussolini, he argues that, despite claims that the Balbo is a symbol of bigotry, the aviator was the only leader of the Fascist party to oppose the anti-Semitic legislation the dictator passed in 1938. "Afterwards," DiFrisco says of Balbo, "he made a point of hosting his Jewish friends in public restaurants to show his disdain and disgust for the law." He says that Balbo was also alone among Fascist party leaders in opposing Mussolini's alliance with Hitler, partly due to the fact that Nazis viewed Italians as genetically inferior to northern Europeans.

DiFrisco points out that Enrico Fermi was also once a member of the Fascist party. The physicist joined in 1929, shortly after Mussolini appointed him to the Royal Academy of Italy. But since Fermi's wife, Laura Capon, was Jewish, he became an anti-fascist and left the country after the 1938 racial laws were passed.

Don Fiore, an amateur historian and former columnist for the local Italian-American publication Fra Noi ("Between Us"), is also against removing the tributes to the aviator, although he says he'd be open to changing the inscription on the column to remove the mention of Mussolini. Fiore also has a dim view of replacing the column and street signs with tributes to Cabrini or Fermi. The saint already has a namesake roadway in Chicago's Little Italy, he says, and the scientist is memorialized by the eponymous particle physics lab in suburban Batavia.

Fiore acknowledges that Chicagoans who defend Balbo's legacy are a dying breed. Most are older residents whose parents witnessed the squadron landing, he says.

One local senior, Water Santi, was actually present himself at age nine. "It was quite a sight to see the planes come in one by one," recalls the 94-year-old retired machinist. "Later on they flew over the city and those noisy, two-engine planes rattled our windows." He doesn't feel strongly about whether or not Balbo deserves the tributes but argued that the debate is a distraction from more pressing issues such as the region's economic woes.

"I know when we're gone [the memorials will be taken down] because there won't be anyone to voice opposition," Fiore says. "But while I'm still here I'm going to say what I'm going to say."