Twenty years after the CTA demolished the one-mile stretch of Green Line tracks between Cottage Grove Avenue and Jackson Park, the former ‘L’ branch is in the news again. Last month Hyde Park resident Reuben Lillie launched a petition calling for the restoration of the elevated tracks east of Cottage Grove. While the petition explicitly seeks expanded rapid transit service on the South Side, it reflects broader issues, too: barriers to funding new transit; anxiety over development, private investment, gentrification; and indignation over the patronizing treatment of South Siders by City Hall.

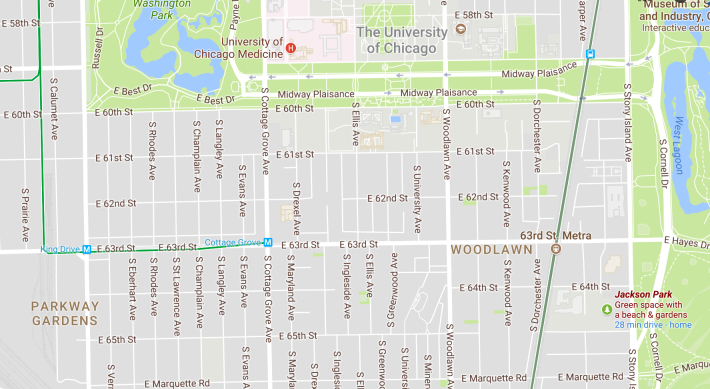

This branch of the Green Line was originally built to bring visitors to the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park. In 1997, after years of deferred maintenance caused the infrastructure to deteriorate, and lobbying by community leaders who argued that the sight and sound of the elevated tracks were discouraging new investments in housing and retail, the CTA tore down the tracks. This was an extremely shortsighted decision since it reduced rapid transit service to the south lakefront, a fact that’s painfully obvious now that the Obama Presidential Center is opening in Jackson Park at 63rd and Stony Island.

When Lillie, a musician and theologian, heard the center would be coming to the park, he was optimistic that decision makers would call for rebuilding the Green Line tracks to serve the new attraction. “I was kind of waiting in the wings hoping the sensible thing would be done,” he says.

Lillie says that when no plans for the restoring the ‘L’ line materialized, he became more “aggressive” in his activism. Mike Medina, a 12-year Woodlawn resident, noticed Lillie’s comments about rebuilding the Green Line online and reached to the Hyde Parker to voice his support. Medina then showed Lillie’s comments to Gabriel Piemonte, a seven-year Woodlawn resident, who also offered to lend a hand with the campaign.

The petition states there is no “viable infrastructure for welcoming people to the Jackson Park vicinity.” It argues that rebuilding the ‘L’ is essential for improving economic opportunities for residents and workers in Woodlawn, which struggles economically in spite of its proximity to prosperous Hyde Park and the University of Chicago.

Proposing the construction of a new piece of sustainable transportation infrastructure is commendable, but it can be an uphill battle. In particular, rail transit is notoriously expensive to build. Kyle Whitehead, Government Relations Director at the Active Transportation Alliance, laid out some of the challenges to expand rapid transit for me. The first hurdle is creating a proposal for the extension and pursuing a public engagement process. However, finding money for the project is usually the main challenge.

“Funding is typically the biggest barrier to…building new [transit lines],” says Whitehead, adding that local funding is especially difficult to come by. While federal grants can help municipalities bankroll public transportation projects, they require significant local funding matches. Currently Chicago has no dedicated source of revenue for transit to meet local match requirements. At the city and Cook County level “we struggle to come up with those funds,” explains Whitehead.

Indeed, Chicago there are plenty of examples of worthy transportation projects with well-developed plans that are stuck on the drawing board due to funding and/or political issues – the Ashland Avenue bus rapid transit proposal springs to mind. Moreover, the Green Line’s restoration to Jackson Park only officially entered the roster of proposed local planning projects last year, with its inclusion in the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning’s list of regionally significant projects.

While none of the men behind the Green Line push are urban planners, they’re aware of the challenges. Through observation and research they recognize the problems inherent to the region’s transit funding formulas, disjointed transit operations, and the politics of planning. Nonetheless, they remain steadfast in the belief that rebuilding the ‘L’ is an essential first step for Woodlawn.

Broadly, the petition is also about establishing local control. “The idea of South Siders being a part of the [urban planning] conversation” is central to the campaign, Piemonte says. “One of the questions that is coming from this is…‘how should Woodlawn be developed,’ and that is very exciting.” Notably, some residents have argued that there hasn’t been sufficient community input on the Obama center plan.

While the Green Line campaign’s focus remains on the ‘L,’ the organizers realize that restoring train access wouldn’t be magical solution to Woodlawn’s problems. Nevertheless, Lillie maintains that rebuilding the line could be an essential element to improving the neighborhood’s prospects. “It’s not a panacea,” Lillie says, “It’s just key.”

After the petition quickly hit 500 signatures, demonstrating support from residents, the organizers set their sights on getting buy-in from decision makers. According to Lillie, Obama Foundation director of planning and construction Roark Frankel expressed enthusiasm about the Green Line proposal when they spoke at a ward meeting. However, the foundation did not respond to my requests for comment on the subject.

The campaigners also want to get Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s and the CTA’s ear. While CTA spokesperson Irene Ferradaz told me there are no plans to rebuild the Green Line section, she added that the authority was open to ideas for improving service. Lillie takes a glass-half-full view of that response, noting that the CTA “didn’t say no,” so this represents an opening to begin pushing for the establishment of a committee to plan the project.

The petitioners want an official response from the city by September 27, the 20th anniversary of the branch’s demolition. This date also falls before planning for the Obama center gets under way in earnest, which would allow the planners to take the ‘L’ extension into account in their designs.

The organizers think it will be impossible for the city to ignore demands for restored ‘L’ service to Jackson Park with the new city-supported development there. “They kind of started the poker game,” Piemonte says. “They say they’re doing [these projects] because they care about the community.” Lillie adds, “We’re calling their bluff.”