[The Chicago Reader publishes a weekly transportation column written by Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield. We syndicate a portion of the column on Streetsblog after it comes out online; you can read the remainder on the Reader’s website or in print.]

The day before President Obama gave his farewell speech at McCormick Place, his administration announced a parting gift for Chicago: about $1.1 billion in grants that, along with roughly $1 billion in local money, will pay for the first phase of the CTA's Red and Purple Modernization Project, a much-needed overhaul of these el lines north of Belmont. Phase one includes rebuilding the tracks from Lawrence to Howard, upgrading signals, and reconstructing the Lawrence, Argyle, Berwyn, and Bryn Mawr stations to make them wheelchair accessible.

In addition, the federal dollars virtually ensure that the CTA will build the hotly contested $570 million Red-Purple Bypass, better known as theBelmont flyover, an overpass designed to eliminate conflicts between Red, Purple, and Brown Line trains just north of the Belmont station. The agency says the bypass will allow them to run 15 more trains an hour between Belmont and Fullerton during rush periods, which will be crucial for addressing overcrowding on the Red Line as the north side's population grows. Leading Chicago transportation experts and advocates have endorsed the flyover plan.

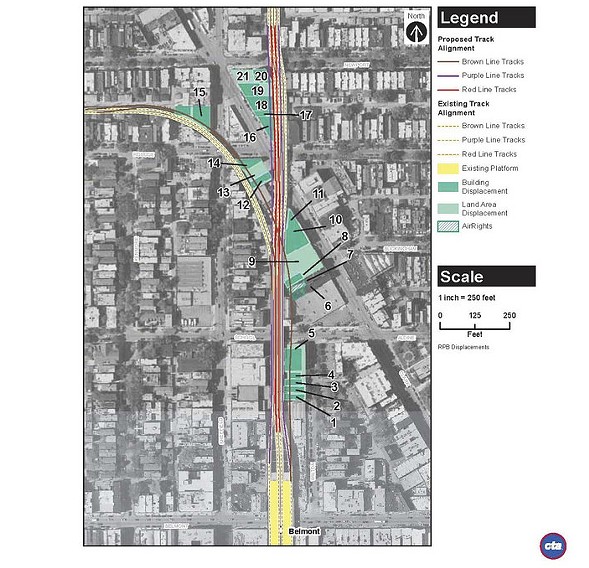

Central Lakeview residents have fought a fierce battle against the bypass, which will require the demolition of some 16 buildings and the acquisition of 21 properties on or near Clark Street north of the station. They've passionately argued that the 40- to 45-foot-high, roller-coaster-like structure is a waste of money that will be a blight on the community, and that the project will scar the neighborhood with vacant lots if the CTA doesn’t follow through with its promise to help redevelop the empty land.

But now that the flyover is more or less a done deal, neighbors I've talked to seem to be taking a cue from the Alcoholics Anonymous Serenity Prayer. They're accepting the fact that they can't stop the CTA's plan, but they're vowing to work for the best possible outcome for the neighborhood by pushing for the gaps to be filled in with quality transit-oriented development and other creative uses of the new open space.

One of the most prominent voices against the bypass was the Coalition to Stop the Belmont Flyover. The group's campaign included an unsuccessfulNovember 2014 ballot referendum that involved the three affected precincts of the 44th Ward, in which 72 percent of the 800-some people who voted did so against the measure.

"The flyover will swing high—60 feet to the top of the train . . . turning a large portion of this thriving restaurant, shopping, business district into a permanent under-el wasteland," the group's website states.

But in an interview last week, coalition leader Ellen Hughes said she has dropped her beef against the flyover and is now focusing on making the best of the situation. She's a grant writer who owns a two-flat on Wilton just north of the Belmont stop. Although her home isn't slated for demolition, "I thought the flyover was bad for the neighborhood," she said, "not just for me."

Hughes says neighbors who heard that the flyover is funded have asked what her next strategy is to fight the overpass. "They were like, 'Let's troll this, let's get them,'" she said. "But it's done. . . . Had we more time or money or people we might have won, but we didn't, and I'm not a person to sit around and be angry. I want to do something positive. Let's make the best we can out of this so the flyover isn't just a blight."

First off, Hughes wants to make sure the CTA keeps its promise to help redevelop the vacant land. She argues that renderings released by the agency that depict future housing shoehorned into narrow lots next to the flyover seem unrealistic, and even if the designs were feasible, the matchbox-like floor plans would make for substandard housing. "Don't just propose housing that might vaguely fit the space that wouldn't be very nice, so no one would want to live in it," she said.