Editor’s note: Streetsblog Chicago sent writer Jean Khut to Atlanta last month to report on The Untokening and share lessons from the event that could be applied to transportation justice efforts in our city. Read Jean’s coverage of the “LA X ATL Exchange” panel here.

Mobility advocates strive to create safe streets and livable communities for everyone. But when advocates who work with or are members of marginalized populations, such as communities of color, try to achieve this goal, they often find themselves at odds with the leadership and members of mainstream transportation advocacy groups.

Frequently, their voices aren’t really heard when they bring up issues in their communities that members of largely white, male, and affluent organizations don’t fully understand or acknowledge. It’s becoming more common for the subjects of equity, diversity, and inclusion to be discussed in active transportation circles these days. But when mobility-related social justice issues, such as gentrification and police abuse, come up, it often makes relatively privileged people uncomfortable.

This was the focus of the Untokening, a convening held in Atlanta last month to discuss injustices and inequity in transportation and public spaces. The event was a companion to Facing Race, a conference held in the city on the same weekend. The day before the Untokening, Tamika Butler of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition and Zahra Alabanza from the Atlanta chapter of Red, Bike, and Green took part in a panel discussion called “LA X ATL Exchange,” moderated by Streetsblog Los Angeles communities editor Sahra Sulaiman.

The panel addressed the question of how people from marginalized groups can do advocacy work in predominately white spaces without being “tokenized” -- forced to serve as the sole representative of their race, for example, or having their social justice concerns dismissed as a distraction from the agenda item being discussed. This theme continued during the main Untokening event.

“We wanted to use this space to name the barriers that exist within the mainstream mobility movement,” said Naomi Doerner, one of the event organizers and a transportation equity consultant based in New Orleans. “[We wanted to] gain a communal understanding of the structural reasons for why justice isn’t currently at the center of the mainstream movement’s frame.”

The Untokening provided a venue for an honest and open discussion of a wide range of subjects, including housing, culture, gentrification, economics, education, and gender, and how these things intersect with transportation and public space challenges. The event drew 130 people who are involved with active transportation issues, from urban planners to community organizers, from across the country. Two-thirds of attendees were people of color.

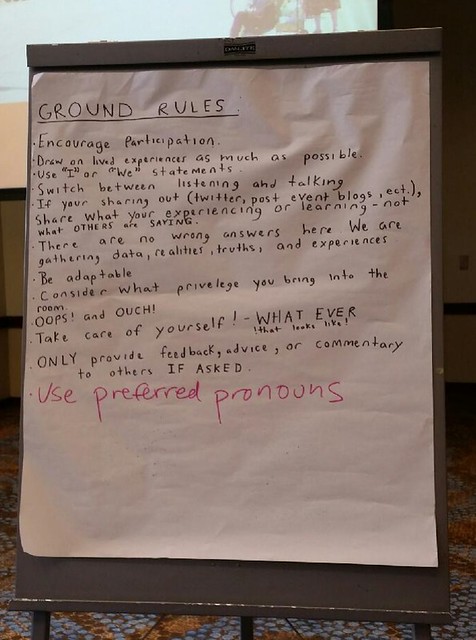

The morning started out with three roundtables on street safety, which included discussions of bureaucratic, socioeconomic, cultural, and physical barriers. In the afternoon, the conversation was extended to gentrification, community engagement, and culture. People were encouraged to identify and address any “elephants in the room” – topics that can be difficult to talk about but need to be addressed.

Some of the issues discussed included white privilege in public spaces; the racial history of highways; street harassment of women; challenges facing transgender people and other LGBTQ folks; the inequities associated with infrastructure investment; and gentrification and displacement in communities of color.

For example, attendees talked about the Atlanta BeltLine project, which is replacing disused railroad tracks around the perimeter of the city with a corridor for walking and biking. Much like Chicago’s Bloomingdale Trail, aka The 606, it has sparked concerns about trail-related gentrification reducing affordability in the area.

Participants noted that plans for new transportation infrastructure or traffic safety initiatives, such as Vision Zero, often overlook the fact that “safety” means different things to different people. It involves more than just building protected bike lanes or writing more traffic tickets. In marginalized communities, discussions of safety may also need to include issues of access to housing, education, and jobs, as well as gun violence and police harassment. Those whose safety is most at risk tend to not be part of the conversation.

Dan Reed, a Washington D.C.-based transportation planner and advocate, told me the roundtables emphasized the need to make space for “people who aren’t traditionally represented in planning affairs.”

Early in the day, many attendees found it difficult to get the conversation going because opportunities for in-depth equity discussions don’t often happen in transportation advocacy circles. But as the day progressed, it became easier to share experiences and offer insights.

“It’s typical for transportation advocates, policymakers, and planners to plan for the most vulnerable people who use the street…[like] a young child or an elder,” said Helen Ho, a bike advocate from New York City. “We have to devise new ways to make streets safer for [people] who are harassed, shot at and killed in our public spaces. After all, what good is a street if people are too scared to leave the house?”

The purpose of the Untokening wasn’t to find quick solutions to the transportation and public space challenges marginalized groups face, but rather to bring these issues to light so that more people are aware of them. Impor, the event brought together a diverse group of mobility advocates and provided a space where they could be their authentic selves, without being tokenized.

Did you appreciate this post? Support Streetsblog Chicago and donate.