For many years Ben Joravsky, my columnist colleague at the Chicago Reader, has provided an important service to the city with his insightful political commentary. He’s been as a key watchdog for local government, speaking truth to power on issues like Richard M. Daley's effort to bring the Olympics to town, and educating the public about complex topics like the tax-increment financing program.

Although Joravsky and I have often differed on matters like the Lucas Museum of Narrative Arts proposal, I’ve never felt the need to respond in full to any of his articles until now. But the column he ran yesterday about the CTA’s rush to get a transit TIF passed in order fund the Red and Purple Modernization while Obama is still in office contains some questionable logic that needs to be addressed.

Joravsky argues that the funding push is an example of Mayor Emanuel acting on his motto “You never want to let a serious crisis go to waste,” taking advantage of post-election anxiety to pass what amounts to a huge property tax hike. “How can the mayor and aldermen say they’re not raising property taxes when actually they’re about to do just that?” he asks.

Joravsky is an influential figure, so it would be a huge loss if his article sways enough City Council votes to kill the TIF plan and, by extension, the crucial $2.1 billion RPM project, which surely wouldn’t get funded under the anti-transit Trump administration. (I didn't provide input for Joravsky's column but I gave him and our editor a heads-up about this Streetsblog post prior to publication.)

RPM would rebuild the Red and Purple Line tracks from Lawrence to Howard, upgrade signals, reconstruct four station and create a flyover just north of the Belmont stop to eliminate conflicts between Red, Purple, and, Brown Line trains. Under Obama, the U.S. Department of Transportation is likely to provide $1 billion in Core Capacity funding to cover the first phase of construction if Chicago applies by November 30. But first we need to line up local matching funds.

Earlier this year the state passed the transit TIF law, which allows Chicago to designate a zone near the RPM project area in which part of any future increase in property tax revenue will be captured in a special fund. The city estimates that this TIF will generate $625 million over its 35-year life span. This captured revenue would be used to pay back a federal loan to cover the local match for the Core Capacity grant.

While tax-increment financing was originally created to help "blighted" communities, Joravsky implies that the transit TIF would have a reverse-Robin Hood effect. He notes that the new district would only exist on the North Side and would include decidedly un-blighted neighborhoods like the Gold Coast, Lincoln Park, and Lakeview, allowing them to keep most of their additional tax revenue in the area rather than sharing it with poorer parts of the city.

However, the faster and more frequent ‘L’ service enabled by the RPM improvements will benefit everybody who rides the Red, Purple, and Brown Lines, and hundreds of thousands of residents across the city live within a ten-minute walk of the Red Line alone. And then there’s all the citywide congestion, air quality, health, and economic benefits of encouraging more transit ridership and less driving.

Joravsky correctly notes that, unlike traditional tax-increment financing districts, the transit TIF wouldn’t divert any money from the Chicago Public Schools, an issue that he’s done a great job of highlighting in the past. Under the new law, the CPS gets the same proportion of any additional property tax revenue that they would receive if the transit TIF didn’t exist.

“But the city, county, and parks won't get the tax dollars they'd otherwise get from this area,” Joravsky adds. “That means that when the mayor looks to spend more money to pay for something like hiring police, he'll likely have to raise property taxes to compensate for the money he's not getting from this TIF district over the next three-plus decades.”

The problem with this logic is that these taxing bodies can’t get their fair share of any additional property tax dollars if that additional revenue isn’t generated in the first place. Here's why that might be the case if the transit TIF isn't passed and RPM doesn't get funded.

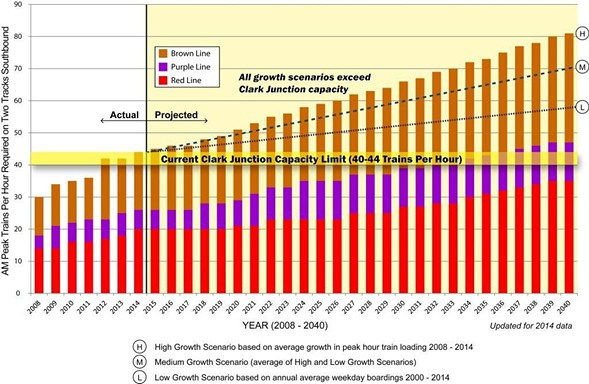

One of the chief reasons why North Lakefront neighborhoods are desirable places to live, with high property values and taxes, is their convenient Red Line access to the Loop and other parts of the city. However, the line is already at capacity during rush hours, and the CTA projects that combined Red, Purple, and Brown ridership demand will double over the next 25 years as the population of nearby neighborhoods rises.

Joravsky has previously argued that the $325 million Belmont flyover is something of a boondoggle, based on his own stopwatch observations of train delays north of the Belmont station. But virtually all local transportation experts agree that the project is necessary for fixing the bottleneck at this location, which makes it nearly impossible to add more rush-hour trains. The CTA says the flyover will allow them to run 15 more trains an hour during peak times on the Red, Purple, and Brown lines between Belmont and Fullerton, which would go a long way towards addressing the capacity problem.

With less-crowded trains, as well as track and signal improvements that enable faster speeds, plus the four new stations providing wheelchair access and a nicer customer experience, commuting by train will become a more appealing option. That will make 'L'-adjacent areas more attractive to homeowners and renters, likely boosting property values and tax revenue within the transit TIF district.

Joravsky doesn’t mention that, after the CPS takes its share of any additional tax money, only 80 percent of the remaining funds would be used to pay back the loan for the train improvements. The other 20 percent would go the other taxing bodies.

Conversely, if the transit TIF doesn’t pass and the RPM improvements aren't made, the ‘L’ will continue to get more crowded and possibly slower, making transit a much less appealing option. If North Side transit service get bad enough, that’s likely to affect people’s decisions on where to live, which could lead to property values and tax revenue staying relatively flat. Under that scenario, it's possible that the city, county, and parks could actually get less additional property tax money than they would under the transit TIF.

With all due respect for Joravsky’s past contributions to the local tax-increment financing conversation, he’s off-base when he claims the transit TIF “amounts to a tax hike, folks.” On the contrary, it’s the only way we’re going to get these critical improvements to the CTA financed under the car-centric Trump administration.

Streetsblog Chicago will resume publication on Monday. Have a great Thanksgiving!

Did you appreciate this post? Consider making a donation through our PublicGood site.