[Last year the Chicago Reader launched a weekly transportation column written by Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield. This partnership allows Streetsblog to extend the reach of our livable streets advocacy. We syndicate a portion of the column after it comes out online; you can read the remainder on the Reader’s website or in print. The paper hits the streets on Thursdays.]

As we stood astride bicycles in the shadow of Alison Saar's Monument to the Great Northern Migration last week, Bronzeville-based transportation advocate Ronnie Matthew Harris, 47, told me that community organizing is in his blood.

"Both sides of my family immigrated from the Deep South as part of the Great Migration, and landed here in the great mecca of Bronzeville," Harris said, gazing at the 15-foot-tall bronze sculpture. "And as long as there has been a historic Bronzeville, you could find an organizer by the name of Harris." His paternal grandfather and father were labor leaders, he explained, and his mother’s job at a local church involved many aspects of community development. "So it’s the family business."

Harris is also passionate about improving conditions in the neighborhood—sometimes referred to as the Black Metropolis—where he was born and raised. As the leader of Go Bronzeville, a group that promotes sustainable transportation options in the community, he'd offered to take me on a neighborhood tour highlighting pedestrian and bike access issues he wants to fix.

"Data shows that a community that walks, bikes, and uses public transportation is a community that is healthier, safer, and more economically viable," he said. "Go Bronzeville wants to respond to some of the inequity in public policy and urban planning that sometimes contributes to disparities in health and wealth."

Go Bronzeville started as an initiative of the Chicago Department of Transportation, along with similar programs in Pilsen, Garfield Park, Albany Park, and Edgewater. The programs educate residents on how sustainable transportation can help them save time and money and improve their health. After the program ended, Harris got CDOT's blessing to continue running Go Bronzeville on a mostly volunteer basis. Nowadays the group hosts neighborhood bike rides, mans tables at community events, and, via a city contract, promotes the Divvy for Everyone program, which offers $5 bike-share memberships to low-income Chicagoans.

To start our tour of Bronzeville's transportation infrastructure, we saddled up and began pedaling south in one of King Drive's wide bike lanes, separated from the street's three lanes of southbound traffic by a painted buffer.

In 2012, CDOT proposed installing physically protected bike lanes on King, but Third Ward alderman Patricia Dowell vetoed the plan after local clergy expressed concerns that the protected lanes would interfere with church parking.

Although he's a bike advocate, Harris said he believes Dowell made the right call. "The cultural norms are different here than on, say, the north side," he said. "Most people would say, 'Well, duh,' but when it comes to urban planning, we don't always keep that in mind."

Still, Harris thinks attitudes in the neighborhood may have evolved since then. "Back then protected lanes were new in Chicago, and the perception was that none of us [African-Americans] are riding bikes, which isn't true."

But that wasn't the main thing Harris wanted me to see. We rolled west on 29th Street to South Commons, a high-rise development just east of Michigan Avenue, to discuss a pedestrian access issue that's very personal to him.

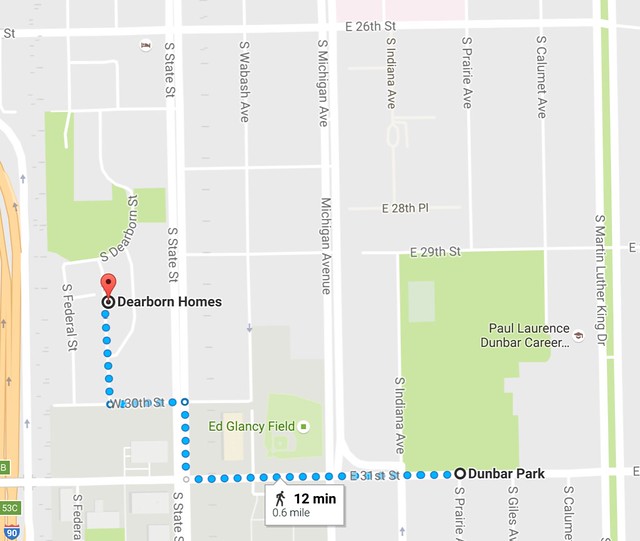

Harris spent much of his childhood two blocks west, at the Dearborn Homes public housing project at 29th and State. When he lived there, there was pedestrian and bike access along 29th all the way from the housing project to Lake Park Avenue, just east of Lake Shore Drive. It was thus possible to travel directly to Dunbar Park, a 20-acre green space southeast of South Commons, as well as to 31st Street Beach.