As I pointed out back in early June when the new Divvy expansion map was released, which included the system’s first suburban docking stations in Evanston and Oak Park, the locations of the ten Evanston stations seemed a little odd.

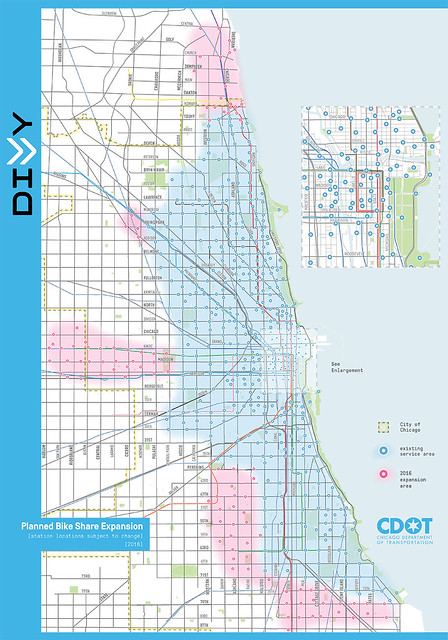

When Chicago originally launched the bike-share system in 2013, a high number of stations were concentrated downtown and in dense, relatively affluent Near-North Lakefront areas, with roughly quarter-mile spacing between stations, in an effort to make the system financially sustainable. The rest of the coverage area generally got less convenient half-mile spacing, using a fairly consistent grid pattern. This half-mile grid pattern was also used for Chicago’s 2015 and 2016 expansions.

One notable exception in Chicago this year is Rogers Park, where there’s a dense cluster of new stations near Howard Street, the Evanston border. “There are a number of logistical and practical factors which have to be balanced when siting stations and it's really more of an art than a science,” Chicago Department of Transportation spokesman Michael Claffey stated when I asked for an explanation of the Rogers Park layout. “These include availability of off-street right of way, parking restrictions and aldermanic support, among other issues.”

Oak Park has distributed its 13 stations using a fairly consistent half-mile grid pattern, similar to what’s been done in much of Chicago.

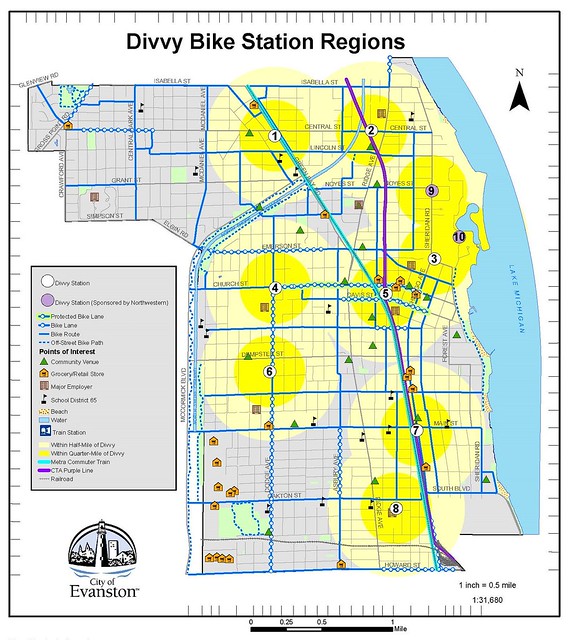

However, the Evanston locations seem scattershot by comparison. There’s no grid pattern, most of the stations are located in the northeast portion of the suburb, and there are almost none in the southwest quadrant, which is relatively close to Chicago.

Divvy's Evanston webpage notes that eight of the ten Evanston stations were purchased via a state grant, with matching funds from the suburb. These station locations were chosen based on data from a survey conducted during Evanston’s bike plan update, a Northwestern University industrial engineering research project, a community meeting, an online survey with over a thousand participants, and paper surveys distributed at a senior center and the suburb’s main libraries. This data was used to identify trip generators and destination points.

The other two stations were paid for by Northwestern, so their locations were chosen to provide access between the other eight stations and the campus, according to the Divvy website.

Evanston’s transportation and mobility coordinator Katherine Knapp provided some additional info on the thought processes behind the location choices. “It’s important to note that we not only have to take into account the street grid, which [isn’t as consistent] in Evanston, but also land use, the distribution of employment centers, and where community resources are located.”

Knapp noted that Oak Park had 13 stations to spread over a suburb with an area of 4.7 square miles and a population of about 52,000. Meanwhile, Evanston’s ten stations had to serve a city of 7.8 square miles and about 75,000 people, which made it especially important to be strategic about locations. Why did Evanston buy fewer stations? “We were trying to strike a balance of community needs with the size of the grant,” she said.

There’s a strong correlation between the Evanston station locations and transit, Knapp said. She also noted that stations were placed along Dodge Avenue (the same longitude as Chicago’s California Avenue), where a protected bike lane was recently installed.

Weight was also given to the parts of town with the lowest rates of car ownership, based on U.S. Census data. This includes northeast Evanston, which features plenty of high-rise housing and “a surprising mix of students and young professionals,” according to Knapp. She noted that the area around the Davis CTA and Metra stops is especially dense with residents and retail.

“When you step back and look at the [Evanston Divvy location] map, it’s been called ‘zany,’” Knapp said. “But when you drill down and look at the demand and what the travel patterns tell us, it makes sense.” The city of Evanston's Divvy webpage includes detailed information about the destinations served by each of the ten stations.

Asked about the lack of stations on the southwest side of Evanston, Knapp noted that this quadrant is less dense than other parts of the suburb. This is partly due to the presence of James Park, a large green space, plus big-box development between Main Street and Howard along the North Shore Channel. She added that some residents of the southwest quadrant will also be able to access stations along Howard in Rogers Park.

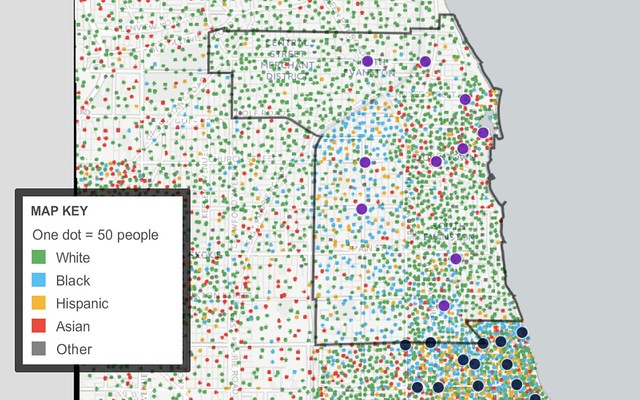

Still, it’s worth noting that much of Evanston’s African-American and Latino population is concentrated on the southwest side of the suburb. Even taking into account the Rogers Park stations, when you superimpose the station locations over a “racial dot map” showing the distribution of residents by race, it appears that Black and Latino Evanston residents may have somewhat worse-than-average access to the system compared to the general Evanston population. Knapp declined to comment on the subject.

A couple of caveats about the above map. It is based on 2010 data from the U.S. Census’ American Community Survey, so the information is somewhat dated, but it’s unlikely that there have been major changes to Evanston’s racial distribution during the last six years. Also note that that the map shows population dots in unpopulated areas such as as parks and cemeteries because dots are randomly placed within each Census tract. While the above map certainly isn’t the last word on this subject, it suggests that the city of Evanston should take a closer look at whether the station distribution is equitable.

According to survey results released last year by , the demographics of Divvy’s annual members had skewed heavily white and affluent, as has been the case with most major U.S. bike-share systems. This was partly due to the fact that stations were initially concentrated in downtown Chicago and on the Near-North Lakefront.

In recent years Chicago has addressed this issue by adding more stations in low-to-moderate-income communities of color and implementing the Divvy for Everyone program, which offers $5 annual memberships to lower-income residents. This summer CDOT is offering free adult bike-handling classes on the South and West Sides to further encourage Divvy use in diverse neighborhoods.

It will be interesting to see how Divvy membership demographics compare in Evanston and Oak Park, which have similar racial demographics, based on the suburbs’ different approaches to station siting. But a lesson from Chicago’s experience seems to be that equitable access to bike-share should be prioritized from day one, rather than addressed after the fact.

Knapp emphasized that these first ten Evanston stations are just the beginning. “Using data from the Divvy system and community we can get information about user demand and where trips are coming from and going to in order to inform future expansion,” she said. “This is a starting point.”