For better or for worse, autonomous vehicles are likely to become an increasingly common part of the urban landscape. At last Friday’s Transport Chicago conference, a panel of transportation experts discussed the possible upsides of conventional cars being replaced by self-driving ones.

The greatest potential benefit would be getting rid of the most dangerous part of a car, according to the old joke, “the nut behind the wheel.” Assuming they’re designed well, autonomous cars would eliminate some of the safety problems associated with human operators, including speeding, red light running, and other types of moving violations, as well as distracted, drowsy, and drunk driving. This would likely result in a reduction in traffic crashes, injuries, and fatalities.

The experts also argued that the new vehicles could potentially diminish the amount of pollution generated by cars, prevent traffic jams, and reduce the need for car parking. This is all true. But according to Active Transportation Alliance director Ron Burke, the panelists, who were all employees of transportation planning and engineering firms, glossed over some of the potential drawbacks of this new technology.

Active Trans, in partnership with Illinois Tech (formerly the Illinois Institute of Technology) will be hosting its own panel on the topic later this month:

Will Driverless Cars Be Good for Cities?

Monday, June 27

5:30 to 7 p.m.

565 West Adams, Chicago

In addition to Burke himself, panelists will include Jim Barbaresso from the planning firm HNTB, Sharon Feigon from the Shared Use Mobility Center, Ron Henderson from Illinois Tech’s College of Architecture. Tickets are $25.

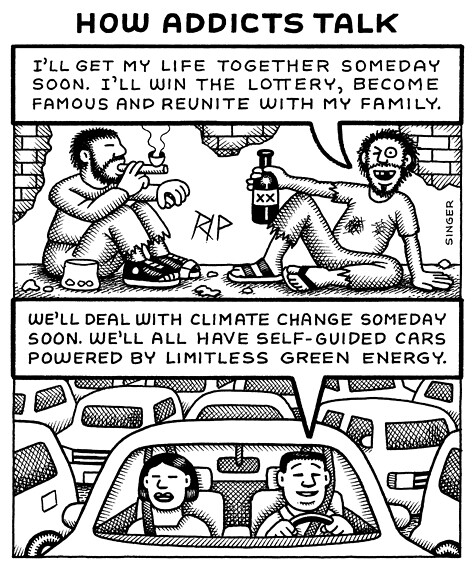

Burke says the Active Trans panel will look at the possible pros and cons of self-driving cars and explore their potential impact on cities. “We decided to host this event in order to better inform our advocacy work,” Burke said. “We want to ask the questions the mainstream press is generally not asking: Is it possible autonomous cars could undermine biking, walking, and transit, and promote car dependency? Their potential safety benefits are exciting, but could they ultimately lead to more driving, not less?”

Burke added that while driverless vehicles could be a net positive for society, the devil will be in the details. One possible scenario would be autonomous cars chiefly being used as part of the shared economy, for ride-hailing trips, or perhaps as a small-scale form of public transportation. That could make it easier for residents to live without owning a car.

On the other hand, if the typical American model of private car ownership prevails, the result could be more driving, greenhouse emissions, and sprawl. “If you can sleep in your car or use your computer on the way to work, all of the sudden an even longer commute might seem more appealing,” Burke says.

Moreover, if self-driving cars become ubiquitous, that could take a bite out of train and bus ridership, making it harder for transit agencies to provide frequent, convenient service, Burke said. And even if most autonomous vehicles aren’t privately owned, paying for Lyft-type service might be beyond the means of lower-income Chicagoans, which would leave them with fewer transportation options than before, exacerbating transportation equity problems.

Burke says the key for ensuring that the driverless cars does more good than harm will be to get out in front of the trend with appropriate legislation, something that cities have struggled with in the face of new phenomena like ride-sharing and Airbnb. “Are there policies that would maximize the benefits and minimize the drawbacks?” Burke said. “We’re raising red flags now so that, when the time is right, we’ll be ready.”