One thing’s for sure: As the current transit-oriented development boom unfolds along Milwaukee Avenue it’s bringing major changes to the affected neighborhoods. Many people agree that adding dense, low-parking development near Blue Line stations is a good strategy for reducing car dependency. But there’s been debate about whether the new wave of high-end TOD buildings is fueling the displacement of working-class residents in these areas, especially Logan Square, or if the increase in housing supply will take pressure off the existing rental market.

A recent article in Curbed provided a snapshot of the changes that are taking place as thousands of new apartments, virtually all of them in TOD buildings, are being built along the Blue Line. It noted that as Wicker Park continues to gentrify, small businesses along Milwaukee are being replaced by chain stores than can afford higher rents.

Meanwhile, hundreds of units are being built in Logan Square with rents ranging from $1,400 for a studio in the Twin Towers to $3,900 for a upper-floor three-bedroom in the “L” building. Ten percent of the apartments in these building will be affordable units, as defined by the city’s standards.

But Curbed noted that, despite the fact that many Chicagoans would never be willing or able to spend thousands of dollars a month on rent, well-heeled folks seem to be lining up to sign leases. A 40-unit TOD at 1515-1517 West Haddon in Wicker Park is over 70 percent leased, two and a half months before it opens, according to developer Mark Sutherland of Wicker Park Apartments.

The building, located a block from the Division Blue Line station, will have 41 apartments (none of which are affordable units) and 21 parking spaces, and rents are similar to the Logan Square TODs. And like the Logan buildings, the Haddon building will include plenty of upscale amenities and perks to partially justify the high rents, including 45 bike parking spaces and a CTA Transit Tracker screen in the lobby.

One thing that’s important to keep in mind is that the rents in these new TODs are expensive not because of the fact that they’ve got relatively few parking spots but in spite of it. Garage spots cost tens of thousands of dollars each to build so, in theory, by providing fewer spaces developers should be able to pass on the savings to their tenants.

But while we know that new construction is expensive, we don’t really have a way to judge whether the companies are charging premium rents in these buildings because they have to in order to turn a profit, or simply because they want to make as much money as possible. Developers like Rob Buono of the Twin Towers have told me that, were it not for the easing of parking mandates brought about by the city’s new TOD ordinance, they probably wouldn’t be building these projects.

Similarly, when anti-displacement activists like Somos (“We Are”) Logan Square have pushed for the percentage of onsite affordable units in local TODs to be increased from 10 percent to 30 percent and the developers have argued that this would prevent them from attracting investors or making a profit, we have no way to tell if this is true. Somos also wants the definition of “affordable” for these units to be changed so that they’re within reach of residents making 30 percent of the Chicago region’s Area Mean Income, rather than the 60 percent mandated by the city.

As I’ve written before, Somos Logan says these steps are necessary because the hundreds of expensive new units in the works will lead to an influx of affluent residents and upscale retail. They say this is encouraging profit-focused landlords to jack up rents, and that it will lead to higher property values and taxes, which will force other property owners to sell their buildings or raise rents, displacing more longtime residents.

Somos Logan spokeswoman Justine Bayod pointed me to studies arguing that increasing the amount of luxury housing in communities has raised overall housing costs, such as “Development without Displacement: Resisting Gentrification in the Bay Area,” produced by the local social justice group Causa Justa / Just Cause.

The report links the construction of 6,000 new units in Oakland, most of them market-rate, with the displacement of working-class residents. It states, “With the arrival of residents willing and able to pay a lot more for rent, landlords saw huge incentives in evicting existing tenants as a way to vacate previously occupied units, and bring in higher income residents.” The study says that between 1998 and 2002, the number of “no fault” evictions tripled in Oakland while rents increased by 100 percent.

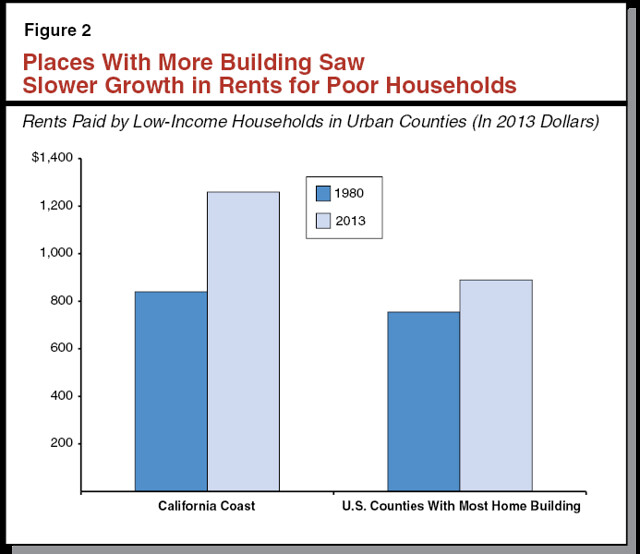

On the other hand, the study “Perspectives on Helping Low-Income Californians Afford Housing,” published in February by the California Legislative Analyst’s Office, makes the opposite argument, claiming that more market-rate housing is the best way to address the state’s affordable housing crisis.

“Existing affordable housing programs assist only a small proportion of low-income Californians,” the report stated. “Encouraging additional private housing construction can help the many low-income Californians who do not receive assistance. Considerable evidence suggests that construction of market-rate housing reduces housing costs for low-income households and, consequently, helps to mitigate displacement in many cases.”

The availability of new high-end units may also reduce the likelihood that higher-income newcomers will buy existing houses and multiunit buildings and replace them with luxury single-family homes.

The perspective of the anti-displacement activists may be colored by their passion for the cause, fueled by witnessing the human toll when low-income and working-class residents are forced to leave their homes due to rising housing costs and evictions. But it’s also possible that the theory that increasing the market-rate housing supply – even with luxury units – is the best strategy for keeping the rents of existing apartments stable is a case of wishful thinking by politicians, developers, and TOD advocates.

It’s a complex issue, and it seems that the jury is still out as to whether the new high-end developments along Milwaukee, enabled by the city’s TOD ordinance, will slow or speed displacement in neighborhoods where rising rents have been an issue for years.

A February blog post by the Metropolitan Planning Council’s Marisa Novara, written after she appeared on a panel on community change along with reps of organizations that are fighting gentrification, including Somos, identified the crux of the matter:

If rising housing costs and displacement are [already] happening, the neighborhood is not going to stay as it was. My top questions then become, How can we shape the outcome of a process that is happening? How can we keep as many longtime residents as possible? And most fundamentally, how do we more effectively get out ahead of these processes in the future?

She notes that, unlike New York or San Francisco, in recent years Chicago has been losing population. A 2014 study by UIC’s Vorhees Center found that only nine of our city’s 77 community areas have gentrified since 1970, so while much of the city faces an affordable housing shortage, there are only a few areas of the city where there’s a housing unit shortage regardless of income.

Although Novara helped lobby for the city’s 2015 changes to the Affordable Requirements Ordinance, she acknowledges that in parts of the city where aldermen mandate that 10 percent of units in new building be affordable, that will have limited impact on the housing shortage. As Daniel Hertz wrote last year, even if that requirement was bumped up to 50 percent in Logan Square, more than 90 percent of units in the neighborhood would still be market-rate.

“So most neighborhoods in Chicago are not growing, and our tools for affordability are inadequate and shrinking,” Novara writes. “Again, what is the outcome we want? We need more neighborhoods to be in growth mode. And we need more affordable housing in all 77 community areas.”

Novara points to the proposed Xavier building in the former Cabrini Green area as an example of a good approach to providing affordability in a growing area. It would combine dense new construction (240 units plus retail) with 10 percent affordable units and 10 percent Chicago Housing Authority units. “This example combines all arguments: We need units in high-demand areas to keep rents from escalating further and to encourage the growth we need as a city, and we need creative solutions to provide as much affordability as possible,” she writes.

Hopefully a similar approach can be tried soon in Logan Square.

![]()

Did you appreciate this post? Streetsblog Chicago is currently funded until June 2016. Consider making a donation through our PublicGood site to help us win a $25K challenge grant that will ensure we can continue to publish next year.