[The Chicago Reader recently launched a new weekly transportation column written by Streetsblog Chicago editor John Greenfield. This partnership will allow Streetsblog to extend the reach of our livable streets advocacy. We’ll be syndicating a portion of the column on the day it comes out online; you can read the remainder on the Reader’s website or in print. The paper hits the streets on Thursdays.]

Residents and aldermen in wealthier north- and northwest-side wards have been more vocal about pushing for bike lanes and racks than their South- and West-Side counterparts. That's one reason why the lion's share of cycling infrastructure has been concentrated north of Madison.

After Rahm Emanuel took office in 2011, that equation changed somewhat. According to the Chicago Department of Transportation, 60 percent of the roughly 100 miles of buffered and protected bike lanes installed during the mayor's first term went to south- and west-side neighborhoods, as defined by the city's official community areas.

Still, when the Divvy system was rolled out in 2013, the bulk of the docking stations went to dense downtown and north-lakefront areas.

In December 2014, a group of African-American bike advocates pushed CDOT to do better, publishing an open letter to the mayor's office requesting a more equitable distribution of resources.

"In the past, the city's philosophy has been that the communities that already bike the most deserve the most resources," Slow Roll Chicago cofounder Oboi Reed (now a Streetsblog board member) told me at the time. "That just perpetuates a vicious cycle where cycling grows fast in some neighborhood and not others." He argued Chicago's African-American and Latino communities are the ones that most urgently need the health and economic benefits of biking.

The city seemed to get the message. When the next 176 bike-share stations were installed in 2015, all new areas received the same station density, and several more African-American and Latino neighborhoods got access. That July the Divvy for Everyone program debuted, offering onetime $5 annual memberships to low-income Chicagoans. More than 1,100 people have signed up so far.

In September, CDOT announced a plan to further level the playing field by doing in-depth outreach on the south and west sides, asking residents where the next round of bike lanes and "neighborhood greenways"—traffic-calmed side streets—should go.

Last week the department held the two west-side brainstorming sessions. Unfortunately, you could count the total number of locals who showed up on one hand.

This may indicate that bikeways aren't a burning issue for residents who grapple with problems like rampant unemployment and gun violence. But cyclists of color say biking can actually help address these challenges, and CDOT is describing its west-side outreach as a success.

Streetsblog's Steven Vance reported that there were only three civilians at Monday's event at the Austin library. And when I asked for a show of hands at Wednesday's meeting at East Garfield Park's Legler Library, only two people indicated they live in the west-side bikeway's planning area, bounded by Austin, Roosevelt, California, and North.

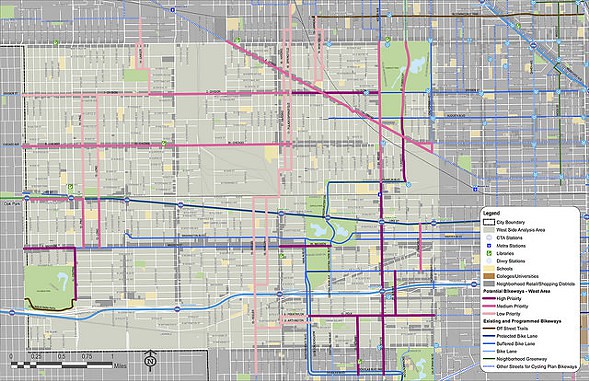

On Wednesday CDOT planner Mike Amsden discussed how the department met with the six alderman in the west-side study area last summer to get their opinions on which routes from the city's Streets for Cycling Plan 2020 should be prioritized. In November they conferred with community organizations like the West Side Health Authority, the Latin American Chamber of Commerce, and West Town Bikes.

Using that input, CDOT gave each potential bikeway street a ranking based on factors like the destinations it serves, ease of installation, community support, and health outcomes along the corridor—which could potentially be improved by getting more people on bikes.

Each 2020 route was given a low-, medium-, or high-priority ranking, indicated by different shades of pink on a map. At the end of Wednesday's session, attendees were given green dot stickers to identify the routes they felt should get bikeways next.