The idea that new bike infrastructure is linked to of gentrification is nothing new in Chicago. Leaders of Humboldt Park’s Puerto Rican community originally opposed bike lanes on the neighborhood’s Division Street business strip because they believed the city was installing the lanes mostly for the benefit of new, wealthier residents. And while the recently opened Bloomingdale Trail elevated greenway has attracted an economically and ethnically diverse crowd of users, many longtime residents are worried that a real estate boom around the trail will displace low-income and working-class families.

Researchers at McGill University and the University of Quebec in Montreal wanted to lend credibility to the claims that cycling infrastructure and gentrification are related. In a study presented this week at the Transportation Research Board’s annual meeting, Elizabeth Flanagan, Ahmed El-Geneidy and Ugo Lachapelle found a correlation between bike infrastructure and socioeconomic indicators related to gentrification in Chicago and Portland.

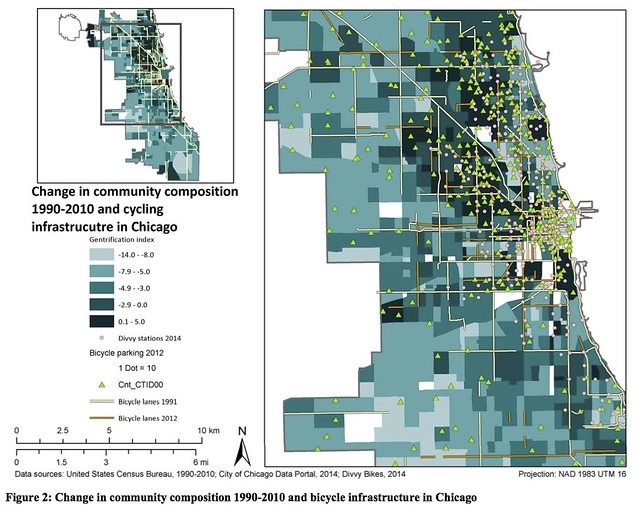

For the report, titled “Riding tandem: Does cycling infrastructure investment mirror gentrification and privilege in Portland, OR and Chicago, IL?,” the researchers looked changes in the rates of home ownership, home values, college education, age, employment, and race in neighborhoods between 1990 and 2010. Then they mapped these demographic changes alongside the locations of bike lanes, bike rack, and, in Chicago, Divvy stations.

While they found that dense neighborhoods and areas close to downtown tended to have infrastructure, they also found that demographic characteristics were a big factor. In Portland, changes in home ownership and education level had the largest influence. However, in Chicago, probably because our city is more diverse, race and home value also played a large role.

The study found that Chicago neighborhoods where more than 40 percent of residents are people of color are less likely to gentrify and have bike infrastructure. Interestingly, however, it also found that, in neighborhoods where 60 percent or more residents are white, a higher percentage of people of color corresponds with more bike infrastructure.

I haven’t had a chance to fully digest the report yet, but it appears that, unlike a recent League of American Bicyclists study that incorrectly claimed that Chicago’s Streets for Cycling Plan 2020 is inequitable, the Montreal researchers used accurate bike infrastructure data. It probably helped that Flanagan worked as a transportation planning intern at Bronzeville Bikes in the summer of 2014, which included discussing transportation equity issues with Chicago Department of Transportation and Divvy staffers.

However, I noticed one statement about the bike-share system in the Montreal report that seems like a jump to conclusions. “Examining Divvy Bike’s 2013 ridership data, it was found that there are in fact so few stations in the South Side that the average trip length of rides originating or terminating in the South Side is over half an hour.”

While the greater distance between stations on the South Side compared to downtown and dense, more affluent North Side areas makes the system less convenient to use, which discourages ridership, it’s not necessarily the reason for longer trips. Less awareness of Divvy’s fee structure, or more interest in taking longer recreational rides may also be factors in why South Side trips tend to be longer.

But the report seems to be valuable for quantifying what we already knew to be the case, that wealthier, whiter parts of Chicago, and areas that have been moving in that direction, have historically gotten a disproportionate amount of bike infrastructure. In recent years, that trend has been reversing somewhat. According to CDOT, 60 percent of bike lane mileage installed under the Emanuel administration has gone to the South and West Sides. Still, many have argued that the decision to concentrate the majority of the first 300 Divvy stations in dense, i.e. affluent, parts of town made the system less equitable.

While the report notes the correlation between gentrified neighborhoods and cycling infrastructure, it doesn’t take a stand on whether the presence of bike lanes, racks, and bike-share are a cause of gentrification, or rather a symptom of it. Instead, the researchers argue that the existing link between infrastructure and privilege suggests we need to change the way that bike amenities are distributed.

“Low-income and communities of color, who would benefit most from increased cycling infrastructure for the economic, health and safety benefits, have been less likely to receive municipal or private investment,” the report concludes. “Mitigating these disparities in the future will be challenging and require rethinking assumptions about cycling culture and planning processes.”

Thanks to Streetsblog USA's Angie Schmitt for providing an interview with Flanagan that informed this article.

Update 1/16/16: On closer inspection, it looks like there may be some issues with the Chicago bike infrastructure data in the new report. On the Chicago map shown above, the white lines are labeled "Bicycle lanes 1991." However, there were virtually no bike lanes in Chicago in 1991 -- the city didn't begin installing bike lanes on a regular basis until CDOT hired its first bike coordinator in 1996. Many of the bikeways shown in white on the map were installed much more recently.

The bike lane data in the Montreal report was taken from the city of Chicago's data portal. A misinterpretation of a bike route GIS layer from the city's data portal was responsible for the errors in the League of American Bicyclists equity study. It's possible that a similar misunderstanding occurred with the new report. In any case, it appears that more review of the Montreal study is needed.

Update 1/81/16: I reached out to the Montreal team about the map issue. It turns out that the white lines on the above map labeled "Bicycle lanes 1991" were taken from an old city of Chicago bicycling map published in 1991, showing off-street paths and recommended bike routes, but few or no existing bike lanes. I've suggested to the team that they contact CDOT to get accurate bike lane data.

![]()

Did you appreciate this post? Streetsblog Chicago is currently funded until April 2016. Consider making a donation through our PublicGood site to help ensure we can continue to publish.