Just because you’ve won a Pulitzer Prize doesn’t mean you always get your story straight.

DNAinfo’s Mark Konkol posted a column today arguing that Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s bike initiatives are a frivolous distraction from the city’s pressing crime, education, and budget issues. He also claims that Emanuel’s administration hasn't been giving low-income communities their fair share of bike facilities. As is often the case when Konkol writes about cycling, he turns the truth into roadkill.

He argues that Chicago’s increasing bike-friendliness is only good news for the people who live or work in the city’s wealthier areas:

That’s where you’ll find most of Emanuel’s protected bike lanes and Divvy Bike stations. It’s another example of the growing economic divide that splits Chicago into two cities — one where the rich get pampered and the other where the poor suffer under Emanuel’s administration.

When the first 300 Divvy stations debuted in 2013, the service area was spread fairly evenly north and south of Madison Street, and a number of low-income communities got stations. However, it is true that the city installed a higher density of stations in the densest parts of town in an effort to make the system financially sustainable. These areas, including downtown and the North Lakefront, do tend to be relatively affluent.

But when the city added 175 more stations this year, they used uniform half-mile station spacing and expanded service to many more low-income areas. While the station density is still higher downtown and in North Lakefront neighborhoods, 23 percent of residents who live within the current service area are below the poverty level, the same as the city’s overall percentage, according to the Chicago Department of Transportation.

As Konkol’s DNA colleague Tanveer Ali mentioned today, CDOT plans to add 75 more stations next spring, largely in low-income West Side neighborhoods. They’re also considering installing more new stations on the South Side.

Konkol wonders aloud whether stations installed in South Side neighborhoods with a relatively low rate of biking may have been “put there to create the illusion of fairness or to meet an unwritten South Side quota.” But in the next paragraph he gripes that the Divvy service area hasn’t been expanded fast enough. That is to say, “The food is terrible -- and such small portions.”

More importantly, while arguing that the Divvy system shortchanges poor people, Konkol ignores the Divvy for Everyone (D4E) equity initiative, which offers $5 annual memberships to qualifying Chicagoans, and waives the usual credit card requirement. Almost 1,000 people have signed up since the program launched in July. Before claiming that Divvy has little benefit for people in low-income neighborhoods, Konkol should talk to D4E members like LaTonya Brown, a United Center Park resident who recently told me she uses the system to commute to work at Navy Pier.

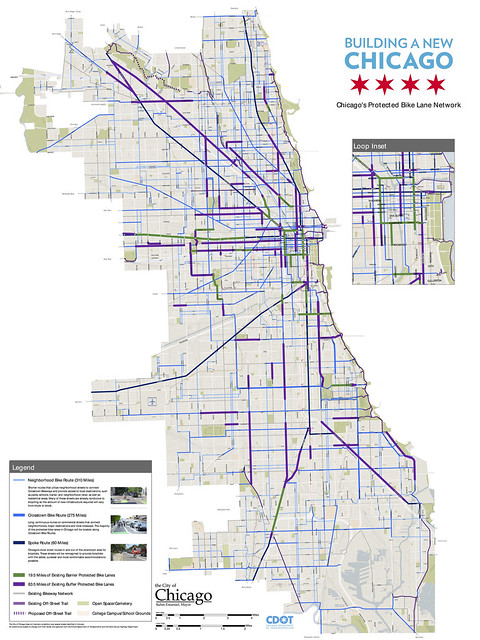

While Konkol’s Divvy analysis is ill-informed, his claims about bike lanes are downright erroneous. “Take a peak [sic] at a map of Emanuel’s highly-touted protected bike lanes and you’ll see most of Chicago’s new, bike-friendly streets… are located in the wealthy parts of Chicago.”

It’s true that, largely due to lobbying efforts by North Lakefront and Northwest Side bike advocates, a higher proportion of bike lanes were installed in those parts of town prior to 2011. However, the current administration is doing a good job of closing the bike lane equity gap. Most of Chicago's new, bike-friendly streets are actually located in the less wealthy parts of town.

Sixty percent of the total bike lane mileage installed under Emanuel has gone to the South and West Sides (official definitions from the city's data portal here), which have also gotten the bulk of the physically protected lanes. In fact, save for a quarter-mile stretch in Uptown, no physically protected bike lanes have been built north of North Avenue.

The worst aspect of Konkol’s piece is that he implies that efforts to build a safe bike network network divert resources from Chicago’s most serious challenges, such as gun violence and wealth inequality. Slow Roll Chicago, an African-American-led group that promotes bike equity on the South and West Sides, argues that the opposite is true.

They note on their website that more bike infrastructure and education in underserved communities will make it easier for residents to access work and school, and will make the neighborhoods more socially cohesive. “We envision bicycles as effective forms of transportation contributing to reducing violence, improving health, and creating jobs in communities across Chicago.”

In other words, bike initiatives aren't a distraction from our city’s most important problems. They're part of the solution.