Planning a useful, equitable, and financially sustainable bike-sharing system in a big, diverse city like Chicago is no easy task. You have a finite budget, and therefore a limited number of cycles and docking stations to work with. You want to provide access to the system for as many people as possible, and you’re certain to get complaints from residents and politicians whose neighborhoods don’t get bikes. However, if you spread the available stations across too large a service area, there will be poor station density and the system won’t be convenient to use.

I respect the the fact that the Chicago Department of Transportation has had to make some tough decisions in implementing the Divvy bike-share system. However, a new study from the National Association of City Transportation Officials suggests that the city may have made a mistake by placing Divvy stations too far apart from each other in many neighborhoods, especially low-income communities. The report, titled “Walkable Station Spacing Is Key to Successful, Equitable Bike Share,” argues that cities don’t do residents any favors by creating sprawling service areas that cover large numbers of neighborhoods, but don’t provide a useful network.

Low station density discourages use and undermines equity

The NACTO paper notes that, while bike-share can be an inexpensive, time-saving form of transportation, low-income people are underrepresented among American bike-share customers. In the U.S., poor neighborhoods tend to have a relatively low density of people and destinations, and when bike-share planners respond to this by putting a lower density of stations in these communities, it exacerbates the usage issue.

The study argues that, just as people usually aren’t willing to walk more than ten minutes to a rapid transit stop, if bike-share stations are located more than a five minute walk from a person’s starting point or destination, that person will generally choose a different mode. That jibes with my personal experience. I'm fortunate to live a quarter mile away from a Divvy station, but I find the five-minute walk to and from the station a little annoying, and if it was another block away I'd probably use it less often.

NACTO’s analysis of several different North American systems supports the five-minute rule theory. They found that the number of rides per day to or from a given station increases according to its proximity to other stations. For example, bikes in New York’s Citi Bike system, with 23 stations per square mile, got more than three times as much use as those in as the Twin Cities’ Nice Ride network, with only four stations per square mile.

Therefore, NACTO recommends that stations be placed no more than a five-minute walk from each other, which they define as 1,000 feet, for a density of 28 stations per square mile. I’d argue that average walking speed is a 20-minute mile, so placing stations every quarter-mile (two standard Chicago blocks), for a density of 25 per square mile, should be sufficient.

Low-income people tend to have less spare time and disposable income than wealthier folks, so they are even more likely to be deterred from paying to use bike-share if the station locations aren’t convenient. The study argues that, while efforts to increase bike-share use by low-income people have focused on offering discounted memberships and providing access to unbanked individuals, the density issue has largely been overlooked.

NACTO recommends having a consistently high station density across the service area, including poor neighborhoods with relatively low population densities. Rather than reducing the number of stations in these communities, the number of docking points at the stations should be adjusted according to demand.

How the city approached the 2013 Divvy Rollout

Let’s look at how the Chicago Department of Transportation has approached equity and station density. When they installed the first batch of 300 stations in 2013, the service area was split fairly evenly between the South Side, which contains many low-income communities, and the North Side, which is generally more affluent. Few neighborhoods on the generally low-income West Side got bikes.

The service area was 44.1 square miles, with an overall station density of 6.8 stations per square mile, including industrial zones and other non-populated areas that didn’t get stations. Station density is somewhat higher when you exclude those areas – the NACTO report, written before the current expansion, lists Chicago’s station density as 8 per square mile.

In this first round of installations, CDOT chose to concentrate the stations downtown and on the North Side, where stations were placed roughly every quarter-mile. In these areas, you’re usually within a five-minute walk from a station, so the system is convenient to use.

However, south of Roosevelt Road, stations were generally spaced every half mile, or four blocks. This southern portion of the original service area includes low-income communities like Bronzeville, Douglas, and Oakland. When you have half-mile spacing, 50 percent of the territory bounded by any four stations is located more than a five-minute walk from a station. If you’re unlucky enough to live in the center of the quadrant, you’ve got a deal-breaking ten-minute walk to a station. This has been a factor in why Divvy usage has generally been low in these communities.

Predictably, there were complaints about CDOT’s strategy. Some people who got only a sprinkling of stations in their communities felt short-changed. And others who didn’t get Divvy in their neighborhoods at all were even more upset.

CDOT officials said they needed to provide a higher density of stations downtown and on the North Side because those areas have a higher density of residents and destinations like ‘L’ stations, job centers, and retail businesses. They argued that, if they didn’t take advantage of the higher potential for use in these areas, the system wouldn’t be financially sustainable, and they’d never get the chance to bring bike-share to more neighborhoods.

Chicago's current bike-share expansion

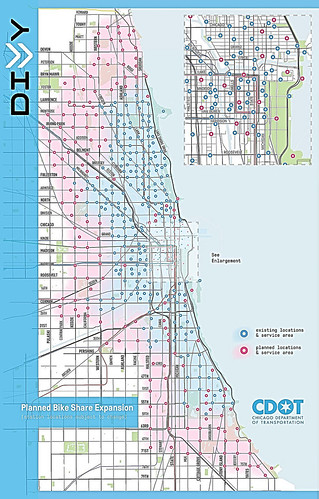

About two years later, the city is now making good on its promise to provide service to more communities, adding 176 more stations and nearly doubling the service area to 86.7 square miles. The number of wards served is growing from 19 to 33, and many low-income neighborhoods are gaining access to the system, including Woodlawn, Washington Park, Englewood, Canaryville, Little Village, Lawndale, and East Garfield Park. And instead of CDOT concentrating stations in the denser or wealthier parts of the new service area, the stations are being equally distributed.

Sounds like a recipe for equity, right? The problem is that, because the service area is expanding to such a broad area, with a relatively small number of new stations, the overall station density is dropping to 5.49 stations per square mile, including unpopulated areas. Almost all of the new areas, irregardless of population density or income level, are getting substandard, half-mile station spacing. Meanwhile, downtown and Hyde Park – just about the only neighborhood with a high bike mode share that got a low station density in the previous round – have received additional infill stations.

The upshot of CDOT’s strategy is that Chicago will remain a city with two different kinds of bike-share neighborhoods. The system will continue to flourish downtown and in the relatively affluent North Side neighborhoods that received quarter-mile spacing in 2013. However, usage will likely lag behind in most of communities that are getting half-mile spacing, especially in the low-income areas that had a low bike mode share to begin with.

6th Ward Alderman Roderick Sawyer has already expressed concerns about just how useful the six, widely spaced stations in the low-income Englewood community will be. "I mean, where are you going that has another Divvy station?" he told DNAinfo. "To that extent, I just want to make sure they get good use, that’s all. If they’re going to be anywhere, they need to be everywhere."

CDOT doesn’t necessarily deserve blame for this outcome. As stated earlier, creating a bike-share system is a balancing act. If they had done half-mile spacing downtown and on the North Side, the entire system would have seen much less use, and might have been a fiscal flop. On the other hand, the agency has received a lot of political pressure to quickly expand the system to new neighborhoods. Perhaps they felt they had no choice but to resort to low-density placement in order to reach these areas.

How the city could have handled station placement and density

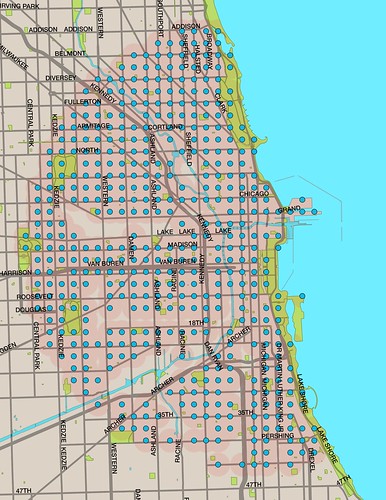

While it's way too late to completely reconfigure the Divvy system, let’s consider what Chicago’s coverage might have looked if the city had used quarter-mile spacing across the entire service area and, with an eye on geographic equity, made the system radiate out evenly from the Loop. As you can see from the adjacent map, which takes into account unpopulated areas, the 476 stations would occupy a semicircle with a five-mile radius.

This strategy would have provided coverage to a little over 39 square miles of the central city, a much smaller area than the planned 86.7 square-mile service area. However there would have been consistently good access across the parts of the city that were covered. As prescribed by NACTO, neighborhoods with low population density, including low-income areas, would get fewer docking points per station, but the stations would still be a convenient walking distance from each other.

The road ahead

If it's the case that CDOT made a mistake by not providing proper station density in most of the service area, what should they do next? Mayor Emanuel has pledged to expand Divvy to 6,000 bikes, i.e. 600 stations, within the next four years. Aldermen in outlying wards have already said they are frustrated that their constituents are getting passed over in the current round. Therefore, the path of least resistance would be to simply repeat the error of expanding the system as quickly as possible, continuing with the substandard half-mile station density.

But maybe a better choice would be to slow down the expansion and use most of the next 124 stations as infill, increasing density in the underserved parts of the existing service area. The focus could be on low-income neighborhoods where residents stand to gain the most from the economic and health benefits of cycling. That might be the best course of action, if we really care about making the system more equitable.