Black bike advocates Oboi Reed, Peter Taylor, and Shawn Conley recently started an important conversation about the need for more bike resources in low-income African American communities on Chicago’s South and West Sides. At a recent Mayor’s Bicycle Advisory Council meeting, they presented an open letter to the city, state, and local advocacy groups, asking that bike infrastructure, education, and encouragement be provided in a more equitable manner. Read the full letter here.

The letter pointed out that downtown and relatively affluent, North Side neighborhoods have generally received a higher density of bike lanes, racks, and Divvy stations than South and West Side communities. The advocates also asked for more input and participation from African-American residents, organizations, and businesses in the planning and implementation of bike infrastructure and programming.

Reed argued that the city has tended to focus bike resources on neighborhoods that already have high levels of biking. This creates a vicious cycle where low-income African American communities get left behind as bicycling continues to grow in wealthier areas, he said. “It just cuts us off from all the benefits, and our communities are the ones that need those benefits the most.”

Judging from statements from the Chicago Department of Transportation and the Active Transportation Alliance, plus comments from Streetsblog readers and on social media, city leaders and advocates agree that more work is needed to achieve bike equity in African-American neighborhoods. There’s a consensus that strong leadership from within the black community, as embodied by Reed, Taylor, Conley, and others in the five black-led bike groups they represent, is a key piece of the puzzle to reach that goal. The groups include Slow Roll Chicago, Red Bike and Green Chicago, Southside Critical Mass, the Major Taylor Cycling Club of Chicago, and Friends of the Major Taylor Trail.

As part of this dialogue, it’s important to discuss what has contributed to the relative lack of bike infrastructure on the South and West Sides compared to some parts of the North Side. In the near future, Streetsblog plans to publish a piece from Reed addressing the “personal, emotional, cultural, structural, and systemic reasons for why we don’t bike much as adults in black, brown and low- and middle-income neighborhoods, and why we don’t have infrastructure in our neighborhoods.”

In the meantime, here are some of the political and geographic factors I’m aware of that help explain the lower density of bike lanes, Divvy stations, and bike racks in Chicago’s African American neighborhoods.

Bike Lanes

As it stands, there are more bike lanes per square mile on the North Side than on the South and West Sides. That is partly due to the fact that the North Side, with fewer industrial zones and less historic disinvestment, generally has a higher population density. It’s also worth noting that the South and West Sides have received more miles of protected bike lanes, largely because these areas have more wide roads with available right-of-way. However, parts of the North Side with high levels of cycling tend to have a more connected bike network.

The biggest political support for bike infrastructure tends to be in places where a lot of people are already biking. In dense, relatively affluent North Side neighborhoods, it's common for residents to advocate for new bikeways and better maintenance of existing ones. Their aldermen are more likely to support CDOT proposals for new lanes, or even use their limited ward money to build and repair bike infrastructure.

For example, 47th Ward Alderman Ameya Pawar recently spent about $150,000 out of his annual $1.3 million in menu funds to create the Berteau Greenway in Ravenswood. The other aldermen who have earmarked ward money for bikeways include Proco "Joe" Moreno (1), Scott Waguespack (32), John Arena (45), James Cappleman (46th), Harry Osterman (48), and Joe Moore (49). All of them represent North Side or downtown districts. In recent years, constituents in the 46th and 49th Wards have voted to spend money on new sharrows, bike lanes, and the Leland Greenway through the participatory budgeting process.

The politics have not always been as favorable elsewhere in the city. When I worked at CDOT in the early 2000s, I heard about several situations where South Side aldermen vetoed the department's proposals for plain, painted bike lanes, based on the belief that they would inconvenience drivers and wouldn't get good use from cyclists. In recent years, the city’s plans for protected bike lanes on King Drive and Independence Boulevard on the South and West Sides were downgraded to buffered lanes after constituents complained that the PBLs would interfere with parking and/or detract from the aesthetics of the street.

Of course, bike lane opposition isn't limited to the South and West Sides -- Jefferson Parkers have bitterly opposed PBLs on Milwaukee Avenue -- but it seems to be most prevalent in areas with low cycling rates. Meanwhile, plenty of people in North Side neighborhoods with high biking rates have been asking for PBLs on streets like Milwaukee in Wicker Park, but haven't gotten them yet because the roadways are too narrow to install PBLs without removing a lot of parking.

Divvy Stations

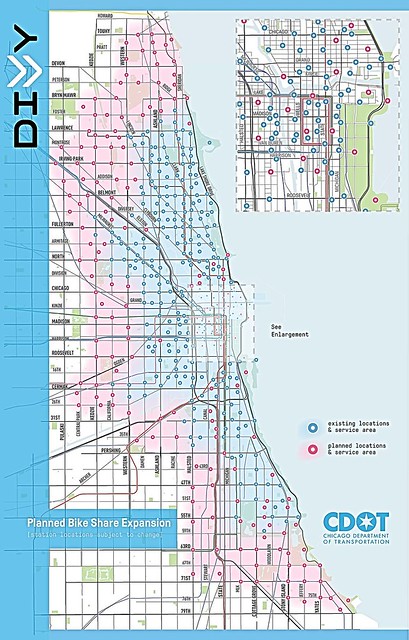

The current Divvy service area is split fairly evenly between the North and South Sides, and several low-income communities of color have received stations. However, few areas on the West Side has gotten bike-share so far, and station density is higher downtown and in more densely populated North Side neighborhoods. CDOT officials have argued that they had to start out by focusing on areas with a concentration of people, transit stations, job centers, and retail in order to make the system economically viable. Their logic was that if the system wasn't financially sustainable, they'd have to shut it down, and then no one would get bike-share.

Now that Divvy is a success and the city has funding to grow the system, they plan to expand to many more South and West Side neighborhoods. However, docks will generally be installed every half-mile, rather than the quarter-mile spacing that’s common on the North Side. Another factor in the North Side’s station density is the online map where residents can request Divvy locations. More requests tend to come from neighborhoods with lots of cyclists and better Internet access. North Side aldermen Moreno and Pawar have also used their discretionary budget to pay for stations.

Bike Racks

Streetsblog’s Steven Vance and I both worked at CDOT at different times, arranging the installation of bike racks. Rack locations were largely determined by requests from residents, merchants, and aldermen. The vast majority of these requests came from neighborhoods with high levels of biking, and that's likely still the case nowadays. We also installed racks at schools, parks, libraries, transit stations, business strips, and other public locations without waiting for requests to come in.

To address the imbalance between the North Side and the South and West Sides, we asked aldermen in low-income neighborhoods to suggest locations for racks, with mixed results. Chambers of commerce in areas like Wicker Park-Bucktown, Lakeview, and Uptown have also paid for branded bike racks using special service area funds, and 49th Ward residents voted to fund bike racks via participatory budgeting. This hasn't happened on the South or West Sides.

In short, Chicago's bike infrastructure tends to go where people request it and are projected to use it, and is scarcer where people have not requested it, or have opposed it. So far this has led to the inequitable situation that Reed, Taylor, and Conley have called attention to. There is a shortage of bike resources on the South and West Sides, and that harms the black communities that stand to gain the most from the health, safety, economic, and social benefits of cycling.

To achieve their goal of extending the benefits of bicycling and bike infrastructure to more African Americans, Reed, Taylor, Conley, and other black advocates are changing this equation by speaking out for the equitable distribution of resources. At the same time, they're doing outreach to build support for bike infrastructure and programming from South and West Side residents and their elected officials. That strategy is bound to pay big dividends if politicians, city agencies, and other advocates are open to their message.