Uptown’s Challenger Playlot Park is the poster child for the anti-traffic camera crowd. Along with Mulberry Playlot Park, in the McKinley Park neighborhood, Challenger is frequently cited as a small, little-used park that’s not even visible from the locations of speed cameras that are supposedly there to protect park users. This is proof, according to the naysayers, that the camera's true purpose is revenue, not safety.

Challenger is a roughly five-acre park located on a narrow strip of land, bordered by Irving Park Road, Montrose Avenue, Graceland Cemetery, and the Red Line tracks. Last year, the Chicago Department of Transportation installed three speed cameras nearby: two on Broadway north of Montrose and one at 1100 West Irving Park. State law dictates that speed cameras may only be installed inside Children’s Safety Zones, the area within one-eighth mile of schools and parks. These three cams sit within those boundaries.

The driver advocacy blog The Expired Meter noted that the southern half of Challenger is occupied by a parking lot, used by Cubs fans on game days. “[Challenger seems to defy the definition of what most people consider a park to be,” wrote the pseudonymous Mike Brockway. “It’s essentially a glorified parking lot next to train tracks. But now there’s a speed camera on Irving Park… protecting the thousands of dead behind the fences and buried in the ground of Graceland Cemetery from the speeders.”

The Uptown Update blog went ahead and implied the cams are a money grab:

The city's new speed camera program says it exists to protect the children who play in Challenger Park, not to plunder your paycheck. If children's safety is paramount, we think it might have been a wiser move not to turn half of the park into a parking lot, but ... oh well. We all know why the cameras are there.

Although Challenger would, in fact, benefit from being de-paved, there are still plenty of reasons to walk there. A fenced in “dog-friendly area” at the center of the park is known as “Challenger Bark.” Just east is Buena Circle Playlot Park, which has a good-sized playground. And the northern half of Challenger is a nicely landcaped green space with walking trails. When I visited on a warm afternoon a few weeks ago, I saw a handful of people with pooches, and a couple of dads taking a walk with their toddlers.

But, granted, one could argue that Challenger doesn’t draw enough pedestrians to warrant the speed cameras. So why are they there?

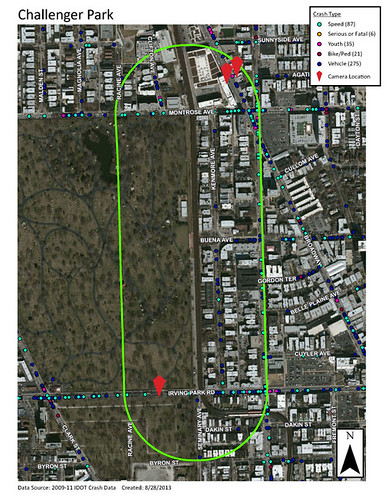

“The Challenger Park Children’s Safety Zone ranks 54th out of 1,400 zones across the city, putting it in the bottom one percent for safety,” explained CDOT spokesman Pete Scales. So far this year there have been a total of 339 crashes within the safety zone, nine of which had serious or fatal consequences. 36 collisions involved children, and 28 involved pedestrians or bicyclists. In 99 of the crashes, speed was a factor.

A crash map Scales provided shows that most of the collisions took place on main streets, and the majority weren’t particularly close to the park. Therefore, it appears that the purpose of the Challenger speed cameras -- similar to the cam near Mulberry – is to address the problem that the general area has a high crash rate. In effect, the cameras aren’t just there to protect children walking to the park, but to protect pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers of all ages, in various parts of the safety zone, from speeding motorists.

This situation highlights a problem with Chicago’s speed cam program. The city really should be allowed to install the cameras anywhere in the city where there’s a speeding problem, not just by parks and schools. However, it seems that Mayor Emanuel felt he wouldn’t be able to get the speed camera law passed in Springfield unless it was sold as something designed to protect kids. As a result, when CDOT uses small parks like Challenger as a justification for installing cams, it provides ammunition for the opponents.

However, that doesn’t mean that there’s anything shady going on here. Sure, the Challenger cams weren't installed to protect children in particular, but they're there to protect all of us.