Yesterday, the Alliance for Biking & Walking released its 2014 Benchmarking Report, which details data and trends about bicycle and walking infrastructure in all U.S. states and in the 52 largest cities. The report enables both public officials and advocates to evaluate how their communities stack up, compared to other communities. It also provides concrete examples of innovative pedestrian and bicycle projects nationwide. How does Chicago compare?

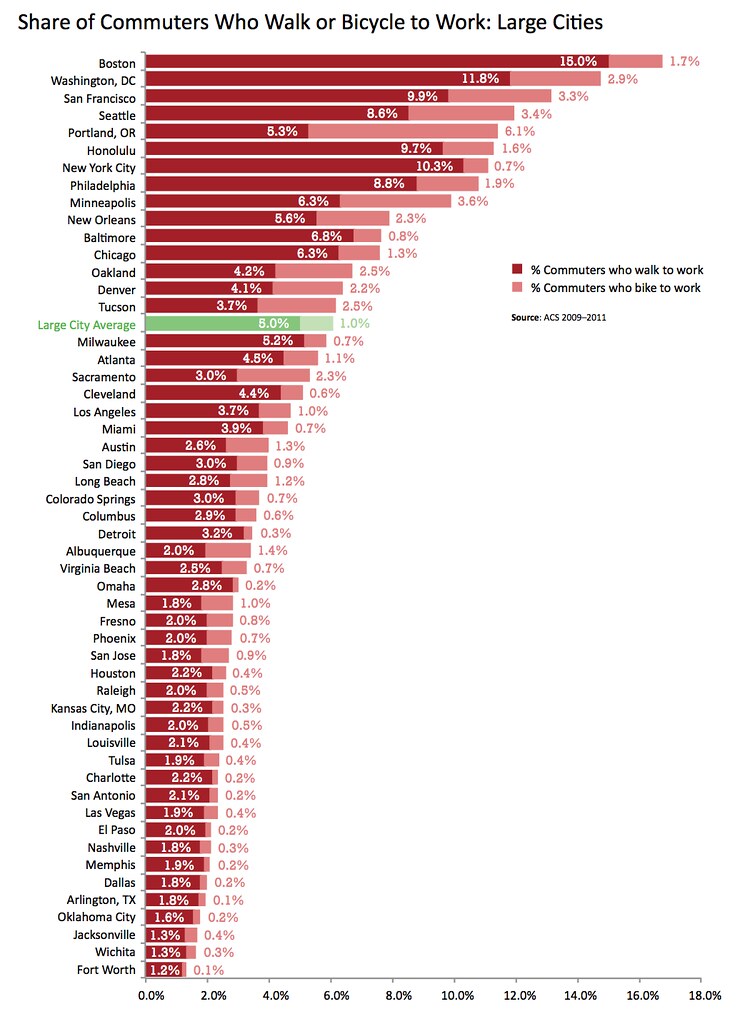

At the national level, bicycling and walking to work have slightly risen or remained flat over the past nine years. In Chicago, 6.3 percent of commuters walk and 1.3 percent bike, more than in the average city, yet still far below cities like Minneapolis (3.6 percent bicycle) or Boston (15 percent walk).

Of course, people don’t just travel to work, and this highlights one key limitation with Census statistics: They don’t measure the three-fourths of journeys that take people to school, or errands, or anywhere other than work. The American Community Survey, from which the report’s statistics on commuting rates is derived, also asks about only the commute mode that was the longest in distance. In transit-rich cities like Chicago, a person bicycling or walking to a train station to get to work counts only as a public transport commuter. With the introduction of Divvy, the number of people using a bicycle to access public transport could increase – but this increase would not show up in the ACS.

It’s also worth pointing out that the bicycling gender imbalance in Chicago is very close to the nationwide average, with 74 percent of bicycle commuters being male. What could Chicago learn from cities like Memphis, Fresno, or Philadelphia, where the gender imbalance is closer to a 60-40 split?

Bicycle infrastructure skeptics often cite Chicago’s cold, snowy winters as a reason why we shouldn’t invest in improvements. However, the report suggests that climate is not as important to bicycle commuting rates as many think. Minneapolis, a city with longer, colder, and darker winters than Chicago, has more than twice as high a proportion of bicycle commuters. Conversely, places where the temperature routinely exceeds 90 degrees have lower rates of bicycle riding. In short, weather really isn’t a factor; rather, perhaps how well the city as a whole copes with weather is more important.

Furthermore, a new federal transportation law that went into effect in 2012 consolidated three different sources of federal funds for walking and bicycling projects into one program. Illinois’ allocation of these funds in this program was reduced, from $42.6 million in 2012 to $28.3 million in 2013. It’s important that our state and region allocate these scarce funds where they can provide the greatest benefit, and make up the difference with local money. As other cities have demonstrated, these small investments can pay off as more commuters choose bicycling and walking.

How does Chicago stack up in terms of what’s already on the ground? Former CDOT commissioner Gabe Klein was a fan of small pilots to test new ideas on Chicago’s streets, and it shows: Chicago is one of two cities, the other being Seattle, that has tried or is planning every type of “specialized bicycle infrastructure” listed in the benchmarking report, including greenways, contraflow lanes, and bicycle traffic lights.

The report does overstate the length of truly protected bicycle lanes Chicago offers. The city continues to count buffered and protected bicycle lanes as the same, stating that 54.5 miles of protected lanes have been installed even though just under 17 miles are actually protected by posts or parked cars. The report does not clarify that distinction, which is formalized in the city-endorsed NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide. This year, Chicago plans to build just 4.25 more miles of truly protected bicycle lanes.

The benchmark report tells us a lot about how our own city and state compare to our peers, but it also highlights how much we don’t know. US Census data only tell us how we’re getting to work, and CDOT hasn’t done many of its own bike counts outside of downtown at peak hours. While growth in bicycle and pedestrian commutes may have stagnated recently, trips for other purposes could be rising. Fortunately, the Alliance has called for a more standardized approach to data collection that combines results from the National Household Travel Survey with data from the American Community Survey. While this is a nice step, it would be great if Chicago could do its own bike counts at non-downtown locations, to really get an idea of where other bicycle trips are being taken.

Knowing how many people are bicycling and walking in Chicago is important, as we look to secure more funding for projects that make these activities safer and more welcoming. It’s great to see that Chicago is trying out new ideas, but more funding should be allocated so that proven solutions, like barrier-protected bicycle lanes, can be installed more quickly and widely. The Alliance calls for local governments to report on how much infrastructure spending will be required to complete their planned bicycle and pedestrian networks. Chicago’s Streets for Cycling Plan 2020 details where our future bicycle network will go, but not how much money we’ll need to get there.