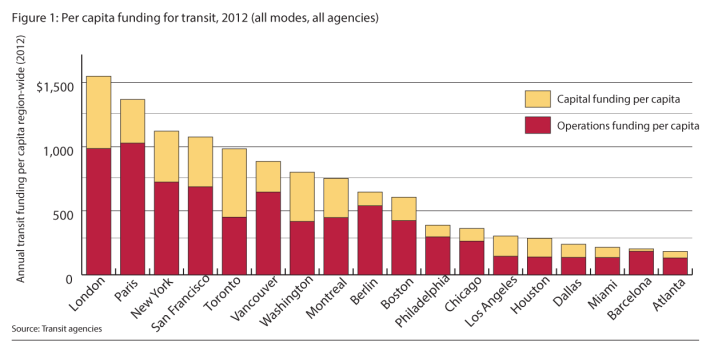

The Chicagoland region "underspends on transit operations and capital" compared to peer cities, and the "region's economic competitiveness will suffer" as a result, according to a recent analysis by the Metropolitan Planning Council [PDF]. The report takes a look at Metra, the CTA, and Pace as a collective system, comparing it to transit networks in 17 other regions.

MPC first notes that despite population growth of 20 percent, the region spent 25 percent less on transit capital investments in 2011 than in 1991. (Of all the regions MPC studied, Atlanta is the only other one that invests less in transit now than 20 years ago.) Combine that with the location of homes and jobs far from existing transit, and, as MPC reports, you get a Chicagoland region where most people now live "far from convenient public transportation."

There are economic consequences to Chicago's shrinking transit funds. The report cites a study linking increased transit service to a proportionally greater increase in gross regional product. "In Chicagoland," MPC writes, "that means that $250 million more annually committed to transit services could produce a $5 to $10 billion increase in [gross regional product]." Report co-author Yonah Freemark says that the development pattern transit makes possible -- with many people and jobs in tight proximity -- "expands employee productivity," because with better access, "people are able to find jobs closer to their skill sets. This results in higher incomes."

Chicagoland has an old rail transit network, so it's reasonable to compare these service metrics in our region to similarly old transit systems, like Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia. Those regions "have funded far larger increases in transit mileage" -- a measure of how much ground trains and buses cover -- between 1991 and 2011, MPC reports. Transit mileage increased by 17 percent in that period in Chicago, while the other old transit systems added between 31 and 40 percent. MPC says Chicagoland transit ranks last among these cities for increases in the number of vehicles operated and total service hours as well.

The report says in no uncertain terms that "the Chicago region has failed to expand its offerings... a direct result of a lack of adequate funding." How would riders benefit if the region decided to catch up to similar cities? The report says that providing more funding for transit would mean "more frequent buses and trains on popular routes" and "maintaining service on lines through transit-dependent neighborhoods." Frequent service leads to more riders, MPC says, because it means a bus or train is there when they need it. Cutting service, as those who lobbied CTA to keep the 11-Lincoln bus, including a vehement Alderman Ameya Pawar, can attest, means many residents lose a vital lifeline to their city.

Chicagoland's meager transit budgets limit the frequencies of Metra trains and their hours of operations. MPC recognizes that freight trains can conflict with Metra operations, but that doesn't explain why the Metric Electric, which has passenger-only tracks, runs "once an hour at middays and on weekends to most destinations." This pattern works fine for rush-hour commuters going to downtown Chicago, but that pattern is rapidly becoming less common. People are working alternative hours, the report says, and there are growing populations of youth and elderly residents and people traveling for personal reasons. Finally, most jobs are not in downtown Chicago.

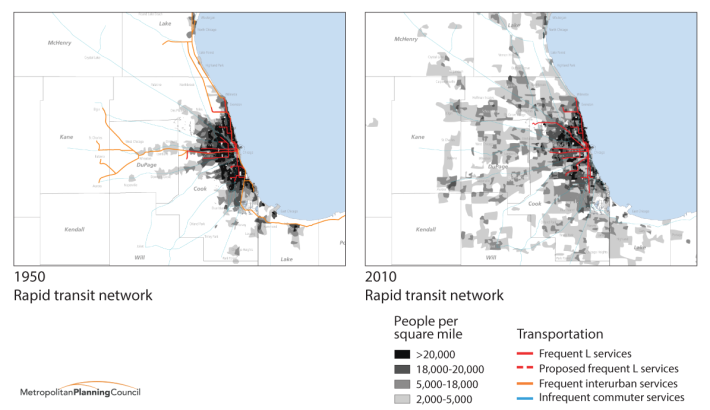

Transit service needs to change to match where people live and work. Paris, a similarly-sized metropolis, has much better suburb-to-suburb rail and bus connections, which run at high frequencies all day and during weekends. MPC notes that New York City and Toronto are "quickly developing round-the-clock frequent services on their commuter rail lines." Chicagoland has actually regressed: A map in the report shows that in 1950, frequent service reached further into Chicagoland from downtown than in 2010. And while 82.2 percent of Chicagoland jobs are in reach of transit, "most of that access is provided by slow and infrequent bus service," MPC writes.

The less transit service available, the less people will ride. Chicago has fewer transit riders per capita than the regions of New York City, Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Boston, and Philadelphia.

Nearly a dozen other American cities have "committed to billions of dollars' worth of new frequent rail extensions," but not CTA or Metra. MPC notes that CTA, Metra, and Pace carry about 150 million fewer riders each year than they did 30 years ago. The transit system reached its low point in 1995, and has been recovering since then. However, CTA trains have accounted for the lion's share of this ridership growth, carrying 50 percent more riders in 2012 than in 1980, while "Pace and Metra carry roughly the same number of passengers."

Why are CTA trains seeing more riders, but not buses or Metra trains? MPC says it's because people require -- and respond to -- the frequent service CTA 'L' provides all day and on weekends.