Today’s roundtable at the Metropolitan Planning Council, “BRT: Moving People, Driving Development” looked at the potential of fast, reliable bus rapid transit to draw investment to urban corridors, and the benefits of transit-oriented development in general. The panel featured CEO Walter Hook and U.S. and Africa Director Annie Weinstock from the New York-based Institute for Transportation and Development policy, which has helped plan BRT systems around the world and is consulting on Chicago’s upcoming projects. Also appearing was Melinda Pollack, vice president for transit-oriented development with Enterprise Community Partners, a Denver-based affordable housing nonprofit.

“The concept of using bus rapid transit to spur some of the same development that we see around train stations, and how do we capitalize on that opportunity, is really what today is about,” said MPC Executive Vice President Peter Skosey, by way of introduction. “We’re going to have a whole new transit line [the Ashland Avenue BRT] cutting through the center of Chicago. How do we plan for that, how do we do land use around that, and how do we attract developers to that opportunity?”

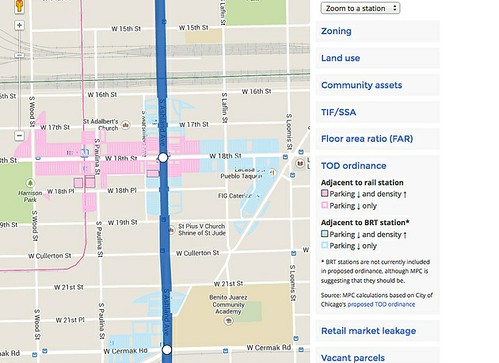

Skosey introduced the new Ashland BRT Corridor Mapping Tool MPC has been working on over the last year to make people aware of the development potential for the new bus line. This online tool allows stakeholders to zoom into a station and see what the current zoning is around that station, as well as features like tax increment financing districts and special service areas. It also shows what the existing square footage of a building is and what the underlying zoning allows. Darker purple shades on the map reveal higher development potential. MPC also recently added a layer to show where the city’s proposed TOD ordinance would apply. “So what you have here in essence is development potential,” Skosey said.

Weinstock said ITDP is about to release a report called “More Development for Your Transit Dollar,” an analysis of the economic impacts of 21 BRT, light rail and streetcar corridors around the US and Canada. “We did this study because there had been a lot of experience in the U.S. about the development impacts of light rail and not so much around the development impacts of BRT,” she said. They also rated light rail corridors using the ITDP's BRT Standard rating system, because they’re similar to BRT in many ways, she said.

The study found that investments in both BRT and light rail can attract substantial real estate development. But per dollar of transit investment and under similar conditions, BRT draws much more real estate investment than light rail or streetcars. They found that the Portland, Oregon, MAX Blue Line light rail and Cleveland's Euclid Avenue Health Line, both silver-rated, spurred $6.6 billion and $5.8 billion dollars in development, respectively. However, the Cleveland system led to about 31 times more TOD per dollar invested than the Portland one.

Hook said that a high level of government support for TOD on a transportation corridor is the most important predictor of success. “Cleveland turned out to be sort of the poster child,” he said. The Health Line connected the two most economically productive anchors of the city, downtown and University Circle, where there’s a concentration of hospitals, universities and cultural institutions. “The land between it was quite blighted,” he said. The city branded it as the Health Tech Corridor, and invested $150 million to bury power lines and replaces sewer and water lines, and built new sidewalks, street furniture and bike lanes. “All of these additional investments into that corridor reassured the developer community,” Hook said.

In addition, the city of Cleveland adopted robust TOD zoning, which encouraged mixed-use development, and required developers to build to the street line, build out 80 percent of lot width, with ground-level retail and a minimum of three floors. “They changed the parking regulations from a minimum to a maximum and they cut that number in half,” Hook said. “It was very progressive zoning for this country. By European standards it’s fairly retrograde.”

Pollack said that Enterprise Community Partners has increasingly made its work about affordable and equitable transit-oriented development. “We’ve concluded many of the same things that Walter and Annie presented to you,” she said. “We’re coming at it as community development practitioners who need that quality for our community development to be a success.”

One example she gave of a successful transit-friendly development is the Dahlia Apartments, which Enterprise bought with money from the Denver TOD fund. Located in northeast Denver, this 36-unit building had been foreclosed. “We used the TOD fund and neighborhood stabilization funds to purchase the property, fix it up, get it reoccupied, build a playground,” she said. “It’s in a neighborhood that’s a block off of a high-frequency bus line that runs downtown. In 2016 it will have rail access but that rail access was really a modest factor. The high level of bus use is really what drove us to consider it TOD and to invest in it.”

When the floor was opened to questions I mentioned that there has already been significant opposition to the Ashland BRT because car lanes will be converted to bus lanes and left-turns will be prohibited. I asked Hook if there have been similar situations in other cities that have implemented BRT and, if so, how was that dealt with?

“Every community grapples with a similar set of issues,” Hook responded. “In terms of dedicating a bus lane, that's usually not that heavy a lift. Because if your buses are already going up and down that corridor they tend to consume more or less a lane anyway because they stop all the time, so somebody’s trapped behind that bus one way or another. If you have a high enough frequency of buses and you give them a dedicated bus lane, you’re probably moving the same number of people that your mixed travel lanes are and you’re probably not doing that much to deteriorate the speed of the remaining traffic.” The CTA is predicting that car speeds on Ashland will only be diminished by 4.9 percent.

“The issue of the left-hand turns always comes up,” he added. “It’s just a misunderstanding of traffic engineering. In most cities on major arterials they’re forbidding left-hand turns without a BRT because it’s simply a question of the speed of the people going straight relative to the time lost of the people turning. So if you don’t have very many people turning and yet you have to add a signal phase to accommodate that movement, it’s not just delaying your busway, it’s delaying everybody going straight. So you should run a cost-benefit analysis to see if it makes sense.” He noted that Chicago’s dense street grid means the left-turn prohibition shouldn’t cause drivers undue stress. “All you have to do is make three rights and you're done. So for us Chicago is a paradise for banning left turns.”